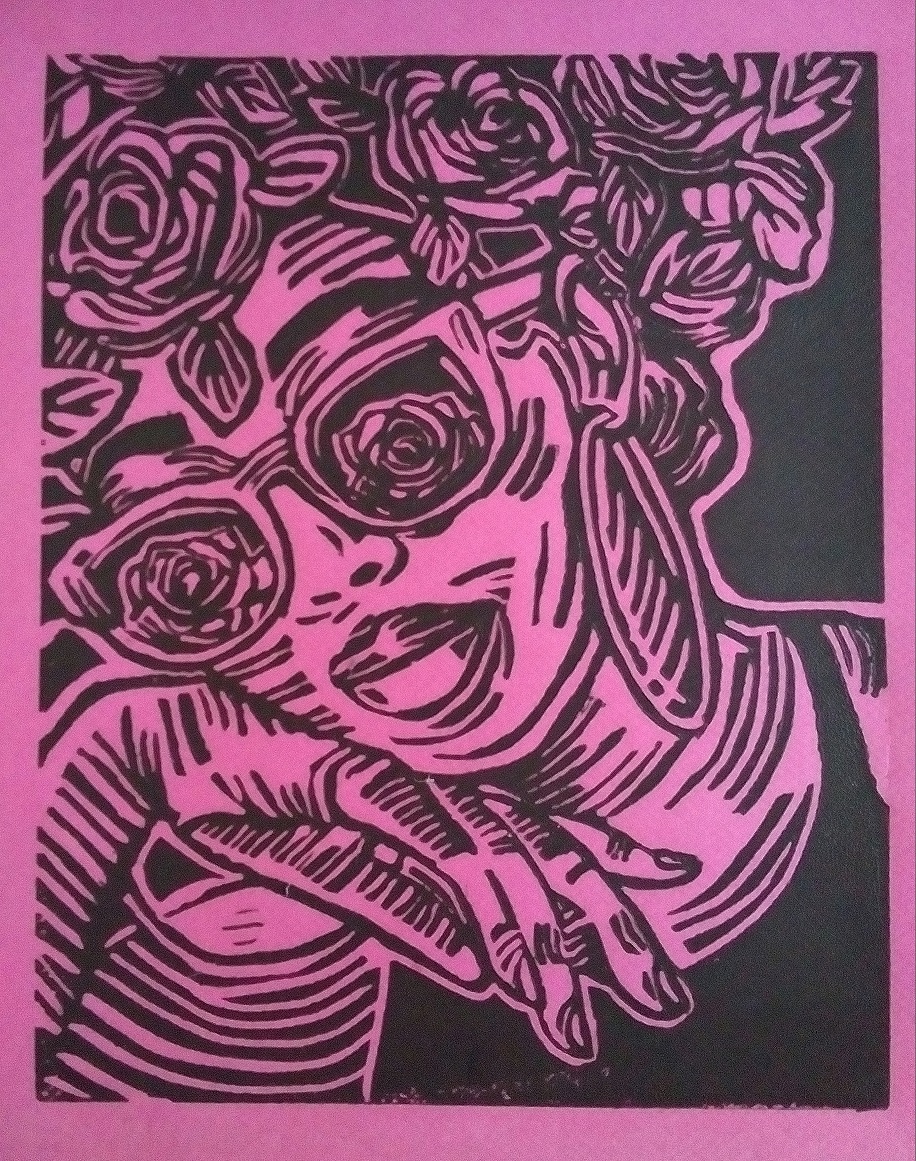

Rose-Covered Glasses, Margaret Wright

I know her like she’s mine. Little sister, little child, little rhyme. We float in the gray-between; one of my hands holds her as a sister while the other tucks her to sleep, maternal lullabies and gentle touch. She doesn’t always know how to define me. I don’t either.

I know her sleep patterns, the 11:47 sleep talk and 2:02 hums. Her arm wraps around me like a security blanket, a pillow, an anchor. I know the sunspots lining her legs, little islands of insecurity. Resembling Hawaii, Greenland, and Ireland, she’s a world of a woman, though she’ll never see it so. I know the thorn scar on her left thumb (It was our first Mother’s Day without one, so she walked a mile to buy me roses. Where she found the money, I still don’t know). I know her nail beds and the way her anxiety picks them raw. She learned that from me.

She has no memory of any maternal figure in health other than myself and I don’t think either of us knows what to do with that.

After our mother first shaved her head, Elise moved her blanket from our parents’ room to mine, curling up next to me each night until our parents bought us bunk beds. Even then, she crawled down from the top, her 3 foot frame cradled in mine. Little snores kept me up but I never woke her. Just hummed her back to sleep when her nightmares whined. She mumbled fears of ‘mommy’s monsters’ and made up medications. Softly singing the lullaby from Love You Forever, I promised her everything.

Our mother’s cancer made its debut just as Elise started Kindergarten, learning letters and comprehension. Old enough to speak, run, and fingerpaint the walls, but not to understand severity. She asked me to explain what was happening, so I used the best of my second grade vocabulary to articulate our mother’s illness. Something about chest, pink, pain, soon. Truthfully, all I knew was I’d blindly promised our mother my bravery–a commitment on which my still-growing hands had little grasp.

I don’t think she remembers the first time she called me ‘Mom’ on accident. I don’t think she remembers the second or third, either. She was 5, 12, and 14, the latter two times being after our mother’s death. I’ve never asked her if she remembers these incidents and I don’t know if I ever will.

When High School Musical was beginning it’s reign, the soundtrack of the first movie never left my stereo. Often, Elise would sneak into my room around 8:30 PM and begin her routine. She’d creep towards the stereo , turn it on, and skip to track two. On the second lowest volume, my room quickly became hers. She shuffled her feet in time with the artificial sneaker squeak bassline and mimicked the way Troy Bolton shimmied around the film set gym. With my eyes barely open, I watched her come alive in ways she rarely did outside my room. Though her song choice confused me to no end–“Bop To The Top” and “Breaking Free” clearly being better options–watching her became one of my Sacred Moments. I would replay the memory when she’d be in screaming sensory fits, when she’d push me out, when she’d call me her made-up playground putdowns. I still replay it now, when it’s 2:19 AM in my dorm and I feel every inch of the 579.1 miles between us.

She always complained to me about her eyes. They look like baby food, Arden. Hers matched our father’s–dusted green and amber. Mine held some shade of which we still don’t know the source, considering our mother’s were a brown of all her own. I asked her what color she’d prefer. I don’t care. Yours are cool. I like Momma’s too. Hers are really smart and nice.

The first time I visited since leaving for college, she had grown two inches taller and her hair two inches longer since I’d last laid eyes. Her heart a little stronger and more spiteful, her mind a little tired and angry. Her eyes softened when she saw me, our bones melting into one another in the middle of an overcrowded parking deck. I don’t remember letting go of her. I just remember looking at her eyes again and seeing more brown than before–she had more of our mother in her than she let herself believe.

About the Author

Arden Stockdell-Giesler · University of North Carolina Asheville

Arden Stockdell-Giesler is a queer poet currently based in Asheville, NC, working as Editor-in-Chief of UNC Asheville’s Headwaters. Her writing primarily focuses on familial dynamics, queer identities, and naturalism within romanticism.

About the Artist

Margaret Wright · Christian Brothers University

Margaret Wright is a Visual Arts major at Christian Brothers University with a concentration in Graphic Design. Although she loves and studies design, Margaret has a soft spot for experimental and traditional art mediums. She hails from Memphis, TN and has had a passion for painting, crafting, and writing from a very young age. Wright finds nature and people as the inspiration for many of her works. This piece first appeared in Castings.

No Comments