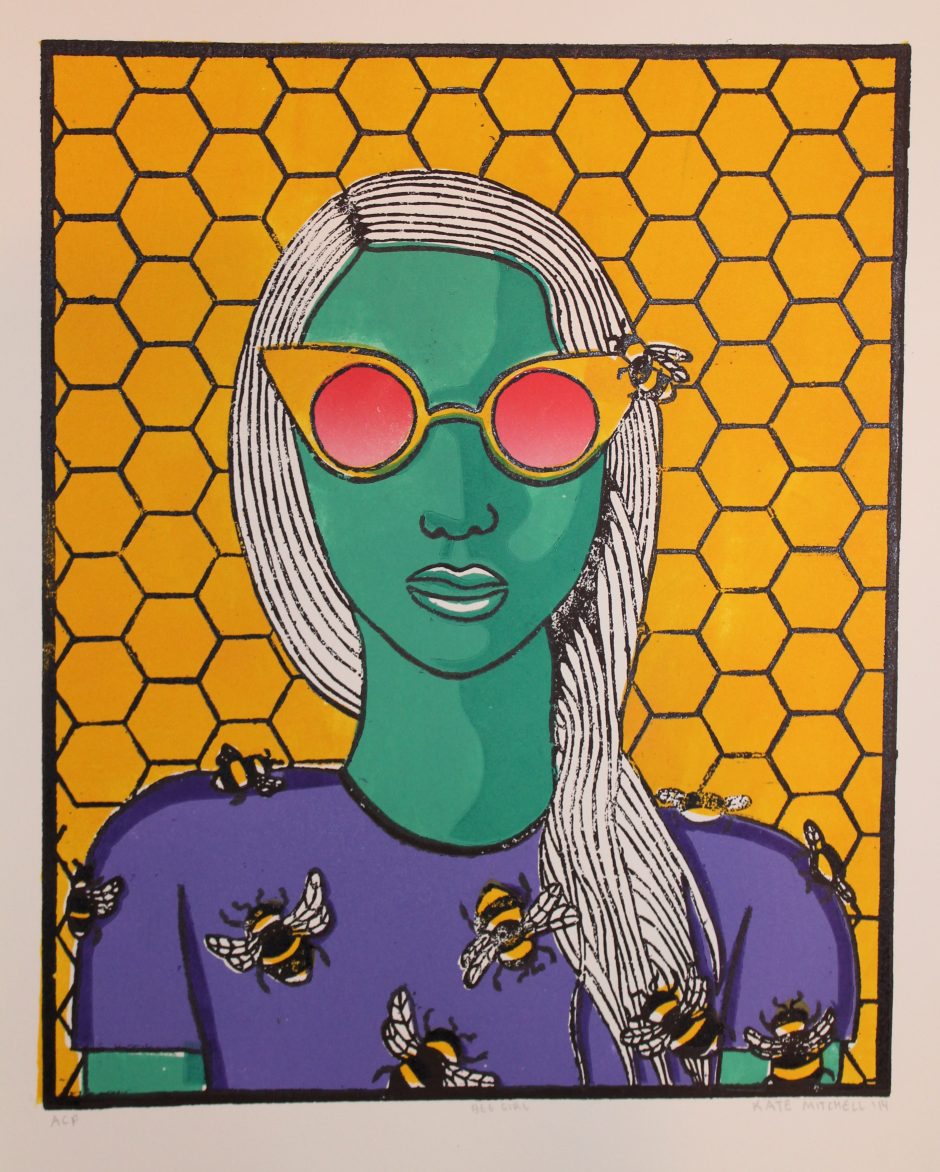

Bee Girl, Kate Mitchell

T-10 minutes and counting

She never used to think of herself as an adventurer, but those were different days and different realities. Maggie is right in the heart of it all—strapped right in and the rumbling’s about to begin. “Please be careful,” says a friendly male voice over the intercom. “You may find the experience mildly disconcerting. Trained personnel will be with you shortly to ensure that your seat belt is secure.”

A seat belt has never seemed so important before. Vital, in fact. As the helmeted figures in white check hers, the woman sitting next to her looks up. “Excuse me?” she asks. Maggie tunes in.

“Yes?” says one of them, a man about her age, maybe, with gray hair.

The young woman clears her throat. Maggie notes that she looks a bit like Kath. “I just wanted to ask your opinion—do you guys think we’re all lunatics?” Yes. Exactly the kind of thing her sister would say.

The man laughs, and tightens Maggie’s belt. Any tighter, she thinks, and she won’t be able to hyperventilate. She doesn’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing. The man doesn’t answer the question.

The voice that isn’t a voice reappears among them, announcing their fate in an artificially cheerful pitch: “Prepare for departure.” The fake voice is tangible and present among the one hundred people who await his words with bated breath. Or is it baited breath? Maggie isn’t sure, but she feels like a fish that can only breathe water, gulping wildly for the promised mouthful, about to be yanked into some kind of unknown emptiness where breathing is impossible.

T-9 minutes and counting

“Where’re you from?” the woman next to her asks, tapping her foot on the smooth white floor to an irregular beat. It rattles Maggie’s nerves.

“Boston,” she says. Her neighbor is a young woman—at least a decade younger than she is—with bright red lipstick, smooth, shiny hair, and a grin that looks stretched out and painful, as if it’s someone else’s smile she’s plastered onto her own mouth. “Cool,” the woman says. “Santa Fe.”

“That’s nice,” says Maggie. The young woman, perhaps realizing that the atmosphere is not the best one for small talk, doesn’t ask her name. And neither she, nor Maggie, nor any of the ninety-eight others ask the obvious question that hovers in front of every single person strapped into a seat: “Why you?”

The woman smiles at her one more time. Maggie notes, scientifically, that her lips are quivering, before she watches them open and hears the woman say, “Well, there’ll be plenty of time for questions later, won’t there?” Her voice wobbles.

Maggie isn’t a talkative or particularly nosy person, but she does sometimes wish that she could read minds, and this is one of those times. She can’t think of any possible reason why a friendly, lipstick-wearing twenty-five-year-old with pretty hair would ever want to leave it all behind.

T-8 minutes and counting

She remembers that headline most of all, loud and insistent across the screen in front of her. Times New Roman. Font size 48. All caps. Bolded. She remembers dropping her spoon into her bowl of corn flakes, the clatter of metal on plastic, the splash it made in her skim milk.

She remembers stopping. Staring. Thinking.

She remembers eating her corn flakes, slowly, one by one, counting how many bubbles they had. Three on this one, two on that one, five on that big one. Like craters.

She’s trying to calm her breathing, so she remembers the hours she spent packing. There were weight limits on luggage—only what you need, they said, but oh, she needed everything—so she had to go through the process over and over again, folding and unfolding and refolding blue jeans and sweaters, hunting high and low for correct sock matches, wavering back and forth between the teddy bear she’d had since she was five and an extra pair of shoes. (She chose the teddy bear and remembering it calms her, stops her stomach from surrendering the few bites of breakfast she forced herself to choke down this morning.)

It’s not working. Her chest feels like an accordion being played too quickly, pumping, pumping, each rare, successful breath a heaving triumph. She’s always been aiming for a melody, but the only thing she can come up with is a jumbled bunch of clashing, painful notes.

T-7 minutes and counting

When she’s panicking, like now, she often remembers the way her life has come crashing down around her. It started out all right, she supposes, as she tries to count the breaths escaping from her lungs uncontrollably, her chest pressing against the hard edge of the seat belt. She got her degree in biochemistry, and then a research position, where she was paid to sit by herself and count tiny, tiny things all day, and she told herself it was perfect.

She’s panicking now and she remembers her sister’s wedding, for some reason. Josh was a wonderful guy, a gentleman, and Kath was so happy that Maggie felt sick. The two of them spent the reception dancing, laughing, talking to their hundred friends. Maggie spent the reception having a panic attack in the bathroom.

She’s panicking now as the air starts to feel hotter and denser, as the sound of one hundred people murmuring rises and falls and rises and falls, wave after wave of worried conversation. She’s panicking now and it feels like the thousands of anxious days and vacant nights and the lack of a good window to look through to find the stars from her hollow, hollow apartment. She’s panicking and it is the most familiar feeling in the world. She’s panicking and she remembers it all.

T-6 minutes and counting

When Maggie was nine years old, she told her mom she wanted a microscope kit for her birthday. She’d circled a beginning scientist’s model in her catalog, but the one she ended up with was a cheap plastic attempt at a microscope. To make matters worse, it was painted bright yellow, putting Maggie in mind of a child’s rubber duck, but she spent hours fiddling with it anyway, counting the veins of maple leaves and flower petals and trying to draw exact replicas of them in her very own scientist’s notebook.

By the time she hit high school, she was spending her evenings counting the pimples on her face in the bathroom mirror. An incurably uncool teenager, she daydreamed of a rocket ship coming to take her far, far away.

She knew her sister thought she was weird. She wished she didn’t care. The two of them were polar opposites; Mom used to laugh about it with her friends, telling stories of the hours Maggie spent hunched over books while little Katherine put on tutus and danced in the kitchen, splashed her fingertips with sparkly nail polish, on and on, story after story. Maggie turned sixteen, got a proper microscope for her maple leaves and flower petals, and spent her days counting plant cells; two months later, Katherine turned thirteen and was out at the mall and the movies and who knew where else with her friends. Maggie used to think of them as a pack of wolves, hunting their prey—whichever middle school girl was unfortunate enough that week to have drawn their spiteful attention. In some cases, their prey was Maggie, despite the three year age difference. “Having fun with your boring numbers, Mags?” Katherine would call from her room, where she and her friends would be, all of them pretty and peppy and popular, all of them laughing at her. “Having fun with your hundred friends?”

Maggie, tucked away at her desk, would pretend not to hear, focusing instead on counting whatever it was this time—colors on the wing of a fly or cells in a piece of onion peel or organisms in a drop of pond water—and trying very, very hard not to count the ways that Katherine was cruel or the times that she, her little sister, the one who was supposed to admire and adore her, had instead made her wish she was someone else, living on a different planet.

Katherine always did seem to have a hundred and more, but Maggie isn’t sure if she’s ever had friends. She’d kept to herself at work, staying late with her microscopes, entering data with precision and care, and fending off the people who occasionally tried to pierce the small, tidy bubble around her and her lab bench with the same precision and care. When the new guy—what was his name? Harry? Barry? Maggie never knew who anyone was—shyly approached and asked her if she’d like to get coffee sometime, she stared at him. She didn’t know what to say, so she blinked at him instead, both of them slowly reddening until he mumbled, “Right, okay, some other time, then,” and backed away. Harry or Barry or whoever didn’t ask her again.

It’s funny, Maggie thinks, struggling to breathe around her seat belt prison, listening to and the vague mechanical beeps and clicks and the hushed murmur of voices around her. Neither she nor Kath would ever have expected this, but she’ll be one of exactly one hundred friends for the rest of her life.

T-5 minutes and counting

The date: Saturday, April 25th, 2093.

The time: 8:25 in the morning. Breakfast. (Corn flakes.)

The headline: MARS COLONY SEEKS RESIDENTS.

The article: A call for applicants to a new colony on Mars that had been finished after decades of planning and construction. It was the beginning, the article said, of a new age of expansion and discovery. They wanted doctors, teachers, researchers, artists. There was, apparently, enough space in outer space for exactly one hundred people.

Kath had sent it to her, with a subject line of “thought you’d find this interesting!” and a link to what her sister didn’t realize was the most important series of sentences Maggie had ever read in her life. She blinked and swallowed and wrote out a quick reply: “Thanks. This is cool. You know me and science. Love, Maggie.” (She’s not good with words, but she’s pretty sure she does love her little sister. She just doesn’t always like her.)

The form was long; Maggie looked it up right after she sent the reply. Potential residents had to be over the age of twenty-one and under the age of sixty-five, in excellent health, and highly skilled. Maggie spent the week locked in her room (a very bare apartment room with sickly green walls and the view from a grimy window of only power lines and asphalt, and she knew it was silly, but really, how could she be expected to deal with this ugly, claustrophobic room, this cramped-in life?), typing furiously. She just barely managed to stop herself from writing down the fact that she was afraid of too many things in this world, that she needed a new one to be properly afraid of for once, that there were too many people on Earth to count and it was impossibly inescapable. She knew; she’d tried everything else.

T-4 minutes and counting

“You did what?”

A fragment of someone else’s conversation, elsewhere in the shuttle, drifts up to Maggie’s ears and hits her like a blow to the chest, real, physical, and she is not in this moment anymore, the moment beneath this seat belt, the moment when the future is almost here. The moment is back in Kath and Josh’s house, when Maggie was visiting, sitting with her corn flakes, counting bubbles, a NASA envelope in front of her, and Kath was there in front of her, hands pressed over her mouth. “You did what?”

Maggie thought it was pretty obvious. “I signed up to go to Mars,” she said, counting three, six, two, four, three bubbles on her flakes before eating her spoonful. “And I’m going.”

Kath just stood there and stared, shaking. It took four more spoonfuls for Maggie to notice the shaking. “Oh, Kath,” she said, but Kath just shook her head, and she stopped. The nerves were coming back. She started counting the polka dots on her sister’s shirt.

“You just—you’re going to—I—” Kath’s lips were quivering as she choked on words. Maggie had never seen her shocked into silence before. (She was on the twenty-third polka dot.)

She knew she should say something. “It’s okay,” she said tentatively. “It’ll—it will be okay.” Kath just kept staring; it seemed that something else was necessary. She wanted to say, I’m thirty-seven and I’m scared to do anything but count. I’m thirty-seven and this particular world is too much for me. I’m thirty-seven and I am sick of this.

Instead she said, “My cornflakes are getting soggy,” and turned back to the craters in her cereal bowl.

T-3 minutes and counting

Everything around her has begun to rumble. The old man next to her—he’s as old as anyone can be here, anyway—turns his head. “This is it, isn’t it?” he shouts over the thunder, glee dancing in his eyes. He claps his not-quite-wrinkled hands together and laughs hysterically. “Everything we’ve all been waiting for! It’s right here in front of us!”

She can’t imagine laughing right now. She can’t imagine anything but panic, so she stares straight ahead and counts the screws in the wall paneling while the old man rambles himself and the rest of them into oblivion. “Prepare for liftoff,” says that invisible other man’s disembodied, present voice. Maggie wonders if the voice belongs to a real person or if he, too, is a machine, mechanically given the semblance of human warmth to make everyone feel at ease.

She suddenly wishes she were home. Not home in her bitterly empty apartment, hating the microwaved meals and the empty other half of the bed, hating the way her breath felt in her throat, hating life until her life became hate; not home in Kath and Josh’s house in Boston with the millions of excruciating framed pictures of their happy, healthy lives; not home at her cold, callous, immaculate lab bench, where she counted and counted for a living. Home, with Mom and Dad, when she was little and Kath was littler Katherine. Home, that old house in Virginia with its yellow window shutters and its lovingly overgrown grass, where she and Katherine shared a room with sturdy wooden bunk beds and blankets with spaceships on them. Home, the big wide window in that bedroom, and the moments when Maggie would wake up in the middle of the night and stare out at the stars, counting them for no reason other than that she felt like it, that they weren’t scary, that they were a constant in the universe and would never disappear, that they always shone from the same corners of the sky. And one day (someone had once told her that all the stars that shone in the sky were long-dead shells, that the bright specks of light that formed her favorite constellations were nothing but projections of the past lives of what were now cold, dead corpses, but, she thought, there had to be some living ones left, didn’t there? Didn’t there?), she’d see them for herself.

T-2 minutes and counting

There is no going back. She can’t get off the shuttle and once it’s gone, she can’t come back to Earth. That is part of the deal, and Maggie has signed it all, every single last agreement and legal document and health form, and so has everyone else, crammed in this sardine can with seat belts like cages over their lungs. And she wants to know why. The man is still laughing, practically crying with laughter, and the young woman, Maggie sees when she glances over, is crying, too. Maybe she should do something about that. She isn’t quite sure, but, well—“My name is Maggie,” she says, and they look at each other. Their eyes meet in space and her neighbor says “Mine’s Ava,” and they smile.

“This is it,” Ava says, after a moment. “Everything we’ve all been waiting for, huh?”

“Yes,” Maggie says. She closes her eyes. This is it.

T-1 minute and counting

There is now, suddenly, immediately, a computerized countdown with a robotic voice that’s driving Maggie insane. It won’t go away. Sixty. Fifty-nine. Fifty-eight. The old man is still laughing and crying, louder than ever above the furious rumbling. Glancing down her row, Maggie sees several of the hundred with hands clasped together in prayer, and several more talking feverishly to themselves, eyes squeezed shut. Some are just silent and stony. Fifty-one. Fifty. Forty-nine. I’ll miss you, Kath, she thinks without speaking, and is unsatisfied. But then, hasn’t she always been? Isn’t that the point of all this? Forty-four. Forty-three. Forty-two. “I’ll miss you, Kath,” she says out loud. Better, but only just, and tinged with a hint of bitterness because it isn’t entirely true. Thirty-eight. Thirty-seven. Thirty-six. What is going on? What is she doing here? She is not the kind of person who should be doing this. She is terrified of eating a corn flake without counting its craters and here she is blasting away from her ultimate center of gravity. The fear is going to kill her. Thirty-two. Thirty-one. Thirty. Halfway to heaven or hell and there are tears in her eyes. If this doesn’t make her happy, then nothing ever will, because this is it, like the old man keeps shouting, this is it, the limit, the maximum, the biggest thing that’s ever been done, and it has to be good enough. It has to be. Twenty-seven. Twenty-six. Twenty-five. Help. Home. That’s what she wants, she wants home, she wants her real window, not the gray expanse of blankness she has in her apartment from which she cannot see the stars, and she can’t stand how her heart shudders when she makes eye contact with anyone else on the planet and she just wants her own planet, if she’s being honest. Kath would say, “Maggie, calm down.” Twenty. Nineteen. Eighteen. They’re into the teens now. When she was a teen she was pathetic and miserable. Where she’s going there won’t be any teens, so maybe they’ll all be teens again, lonely and isolated and joyful and free. Fifteen. Fourteen. Thirteen. She is vividly reminded, for no real reason, of the first microscope she ever had, the rubber-duck-yellow plastic toy, and she wonders what she’d see if she put her mind under that age-old lens. She’d count the folds of her brain like the rings of a tree to see how tired she is. Ten. Nine. Eight. Kath must be watching on TV, curled up with dear loving Josh, maybe sobbing. Maybe. Seven. Six. Five. Maggie is crazy, wild, elated. Four. Maggie is desperate, crying, terrified. Three. She just wants to get going. Two. She just wants to leave the world already. She just wants to breathe and breathe and always breathe. She just wants another chance at the kind of life she used to think she could have, back when she counted the never-ending stars outside her bedroom window. One. God.

Zero.

No Comments