Closed Circuit, Marielle Saums

[Trigger Warning: Animal Dissection; Death Mention]My high school biology teacher can tell the sex of a fruit fly as it floats past her head. “Male. Female. Oh, there goes another male.” Sometimes she counts them during class if they happened to escape their jars. She could be talking about the mitosis in cells and then pause to check the room’s new ratio of girls to boys. The female fruit flies have long, thin abdomens with pointy wings. The males are bulky and round.

We don’t have to distinguish the difference in sexes while they’re flying. We stick an elongated Q-tip into the bottle of murky brown liquid and place it into the jar where the fruit flies are living. The bottle has a cartoon of a fruit fly lying on a bed with a nightcap on its bulging head and Z’s pouring from its mouth. It looks content.

Within minutes the flies in the jar stop buzzing and bumping into the glass. Some of them fall off of the wad of paper towel we stuffed in there for them to climb on. They land on their backs with their legs sticking crooked in the air like six burnt hairs. They look dead.

Idon’t mind the use of animals for the needs of humans. When we cut up the crustacean I broke off both of its claws and had a battle with my lab partner. I had fun with the cow eyeball, tapping the clear disc lens on the dissection table to the tune of “La Cucaracha.” It actually feels like hardened plastic. The pig brain was boring. I cut the hypothalamus needlessly into six pieces. For something so mysterious the brain looks a lot like a wad of ground hamburger. It cuts and smells like a mushroom.

Skinning a cat wasn’t a problem. I was more worried about the feel of the white powder from the medical gloves than the glossy smoothness of the underside of the detached skin. My cat was thinner than the others. When I opened him up, I was upset that there was less buttery white fat to cut off. Every day we had to put his little coat of skin back around his arms and abdomen to keep in the juices and dampen the muscles. We didn’t cut off the white fur around his paws. They made him look like he was wearing dress shoes and formal gloves. At the end of the day when we wrapped his black skin back around him it looked like a tuxedo. I always felt as if we were dressing him up for some kitty gentlemen’s club. He would smoke catnip cigars and pick at thirty dollar fresh salmon, but really we would just drop him into a plastic bag, dripping with excess formaldehyde, tie it like a bag of bread, and throw it in the freezer.

If you were to open the base of your skull like a lid on hinges and poke your brain with a cotton swab, you wouldn’t be able to feel it. Not even if you traded the swab for a Black and Decker hand mixer and turned your brain into pudding. There are no nerve endings for feeling there. Any pain would be in the tissue of your scalp and the membrane that protects your brain like a cushioned holding room for the insane. What’s worse is that brain cells are the only kind that can’t multiply. If there’s any reason I would believe that humans have a soul, it’s because the brain is really just a piece of meat. It’s so simple that it’s impossible to understand how it can form such complex and unique concepts. There has to be something else in there that the scientists can’t grasp. Not even with their bare hands.

When the fruit flies stop moving we use extra long tweezers to take them out of their two jars. One contains only males, the other only females. We sort them further, looking through hand lenses to see if they have black or red eyes. I wonder if the ones with black eyes look at everything like they’re wearing sunglasses. That would make it hard to see at night—no wonder they’re always searching for the light.

Idon’t know how old a person has to be to start talking about their death and make you worry about it happening. I’ve had plenty of conversations—in lunchrooms, classrooms, living rooms, around an outdoor fire—about what the best way to die is. I hate it when anyone suggests tying rocks to your feet and jumping in some pond or river. There’s way too much time to change your mind with no hope of swimming back up to the surface. The conversation always ends with wanting to die in your sleep, but there’s something creepy to me about dying and not knowing it.

I can’t remember when it really started: the feeling right before I’d fall asleep when I would remember that someday, sometime, I would die. It happened even when I was seven, before we moved, and I would try to find that Disney star in the sky that answers wishes. Every night I wished my Dad weren’t allergic to cats anymore. Then I would lie back in bed, pull the cord on “Jaffy” my stuffed giraffe that hung over my bed and he’d play, “If I Could Talk to the Animals.”

I might think once about the door in my room that led to the attic, about a gigantic slug monster that would leave a trail of slime down the steps, leading up to my bed, and gaze down at me. Even at seven I knew this wasn’t feasible. There weren’t really monsters, but that feeling, like a black hole in my throat, would grow until it made my head tingle and I’d remember. I’d give Jaffy another tug, turn on my side toward the hallway light and try not to imagine when its bulb would suddenly flicker and go out.

As I examine each of my thirty or so fruit flies through a hand lens I can’t help but look at more than their eyes. In between my tallies of red versus black, I notice the shapes of the wings, the mouths, the small bristles of hair that lets them walk on walls. I am slower than the rest of my class, and I find my table of lab partners staring at me when I raise my head for a moment.

“I think I found some kind of genetic mutation!” I say. “A few of my flies have a weird purple tint to their wings when you hold them to the light, see?”

I pick up one of my special flies I had saved separate from the others and turn it side to side in front of their faces. “And what’s really weird is that these flies have almost whitish eyes, like they’re blind or something.”

They don’t seem very excited about my discovery; they just want to get their packets checked off so they can talk or work on homework for another class. I can’t really blame them. After all, I’m talking about fruit flies.

When I went to take the written exam for my driver’s license, I forgot they were going to ask me whether or not I wanted to be an organ donor. I wouldn’t need my liver or eyeballs if I died, I knew that—but there was something weird about not knowing what they might take. As though someone would be stealing my memories or part of my personality instead of a clump of specialized cells that would save a life somewhere.

My brother and Mom were both donors, so I told the large lady with equally large glasses behind the white linoleum counter I would be, too. The DMV smelled like cow manure and two different babies were having a crying contest, so I didn’t take much time to think about it. When I got home I found out my dad wasn’t a registered donor, and I felt I should have waited at least the first four years until I got a new license to make such a huge promise. Then I remembered my dad also planned on being cremated. Now it just seemed like he was being selfish.

My mom has started saying that when she dies she could be a teacher forever if she donates her body to science. “I could be one of those skeletons they have in classrooms,” she says. I tell her to stop talking about it. It makes me feel weird. All I can think about are my friends who plan to enter medical school picking up my mom’s jaw or tibia, and using it to pass a test.

Some of the fruit flies are starting to move before I’m done counting.

“That’s okay. Their wings will be the last to become un-paralyzed. They won’t fly away.” Ms. Myers assures me.

“I thought they were just asleep.” I look over again at the ugly cartoon fruit fly catching Z’s on his tiny fly bed. One of my female flies is stretching her legs in the air, moving them back and forth like she’s doing bicycle exercises in an upside-down spinning class. It’s strange to think a thing weighing less than a drop of sweat can still burn calories.

Every Memorial Day, the parade ends at the cemetery and they have a little service. The marching band plays a song, first graders sing, an eighth-grade boy recites the Gettysburg Address, and an eighth-grade girl recites “In Flanders Fields.” I was that girl in eighth grade, and now I hate to hear them read it — three times shorter than the guy’s part and way more boring. I had needed to use notes, even though it rhymed. I felt like an idiot after Drew Eiswerth followed me with his speech perfectly memorized. All the first graders were quiet and it felt like even the tombstones were listening.

After the service every year my family goes down to the Hess family plot and we look at names of people I’ve never known. Our section is easy to pick out because the Hess stone is huge with sloping corners and two tall arrow tipped bushes that stick up on either side. My grandfather is buried there, his date of death two weeks before I was born. Under his name it says simply, “He Lived.”

Next to his stone is the one for my grandmother, “Carlene Hess, wife, mother, grandmother.” And then her date of birth and a dash with nothing following. She isn’t dead yet, but I’ve had to read her name on a gravestone every single memorial day, even when I was a first grader singing “America the Beautiful,” on top of Cemetery Hill.

“When Dad died, they wanted the printing to match,” my father explains.

I don’t see how this is a good reason. If your name’s on a tombstone, your body should be beneath it. I hate that I can’t help but try to make up dates that will fill the empty side of that lonely dash.

When I was in junior high my dad became the president of the board for the Hughesville Cemetery. I liked to call him the King of the Cemetery. It’s nice to know you’re related to someone who has some position of control when it comes to being dead.

Ihurry to pick up my fruit flies, throwing them back into their jars before they completely revive and realize they can escape. This time our class disperses the males and females evenly among each other, hoping they will mate so we can have another generation to compare genetically determined characteristics like eye color.

“Next time we have class there might be some fruit fly babies!” Ms. Myers says this like these babies will be cute and giggle when you poke them, but really they’ll just be squirming maggots.

“What do we do with the adults when the new generation is born? Are we going to let them go out the window?” I wanted to know. It would ruin our study if we couldn’t tell the difference between the two generations.

“No, the weather is too cold outside, they would just die anyway.” I look out the lab room window and see the school’s pine trees bracing against the wind, their faces looking down, their trunks straining like gritted teeth. No fruit fly could make it in that kind of cold.

“Then what do we do with them?” I ask.

Our school sits right at the base of Cemetery Hill, the highest point in the borough. On snow days when kids park their cars at the base of it and sled down, you can see the school on the way down, and it almost feels like you’re about to hit it until the large pines and street of houses rise over top and the walls disappear. There’s a road that runs down from the cemetery gates to the school parking lot, which means the school’s address is Cemetery Road. I always thought that was kind of funny, just like in eighth-grade Pennsylvanian history when we had to memorize all sixty-seven counties and we’d eventually cover Schuylkill. Sounds like “School-kill.” I always remembered that one.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place—

Little pieces of white rice wiggle around inside the fruit fly jars. They can barely move, just shaking like they want to sit up, move around, grow wings. Ms. Myers brings out the bottle with the stupid cartoon of the sleeping fly again, and the long Q-tips.

Even the maggots stop wiggling, but we use our pliers to pluck out just the adult flies. First generation. G1. I put my sleeping flies, about twenty of them, in one pile in front of me on the black, flame resistant counter. Can they feel the sharp pliers squeezing their wings? There’s another bottle of liquid, this time yellow, this time the picture isn’t a cartoon: it’s a fruit fly, a normal one.

“And then you just drop them in.” Ms. Myers demonstrates by picking up a fruit fly with her tweezers and dropping it into the Petri dish filled with the yellow substance. The fly falls, immobile, no chance to fly away, to go live, mate, and have rice babies in some corner of the school.

I hadn’t minded cutting apart a cat’s muscles, labeling them by tying string around the tendons and writing its scientific name on a card. Even when we had to crack the jaw to get to the mandible muscles, using the industrial pliers to break the bone didn’t bother me. But this was killing, and even that wasn’t so bad, I’ve probably killed a hundred fruit flies on the softball field just by blinking at the wrong time. The difference is that they are paralyzed, can’t even attempt to escape. The difference is—they don’t know.

For years, the foreboding feeling kept coming back night after night, as soon as I closed my eyes. Once I started thinking about it, I couldn’t stop. How long would it be? Let’s say I live till eighty, what fraction have I already used up? About an eighth then. How much longer do my parents have? My grandparents? The old lady up the street?

But these kinds of thoughts weren’t even what would really keep me up at night. The worst was was not knowing what fraction of my life was already used up. I pictured it like a circle graph, filling with a red percentage. Once the circle was solid, well, I guessed I wouldn’t have trouble sleeping anymore.

I pictured bombs, all kinds, dreamt about them. Little bouncy balls that could hop across continents and explode entire counties and cities each time they bounced. “Goodbye, Schuylkill. Goodbye, Philadelphia”—they would hop their way like that across the country. And somewhere over in Asia bearded men would be laughing and watching it all on the Internet.

Being dead doesn’t seem that bad, I mean, how can you feel sadness or regret if you’re dead? I tried to practice, closing my eyes and crossing my hands over my chest as if I was were in a casket, trying to see only blackness and force out all of my thoughts, but it was impossible. It was scarier to imagine the body dying and the mind still working, having thoughts and being trapped underground in a coffin with maggots crawling on and under my kneecaps. The darkness of death wasn’t scary, as long as I could persuade myself that I wouldn’t have a mind to see it.

In biology we learned that the brain is the boss of the body. That our feelings and movements are all controlled by sparking neurons like a big electric switch board, dispensing energy into signals that travel through the body and send different messages to worker enzymes and cells that carry out the instructions. I want to know who these scientists think is sitting at the stool in front of the switchboard transferring calls and making connections like a 1950’s operator. They don’t know, don’t even have a clue. I guess that must be what Descartes called the mind and good Christians call the soul.

Ionce asked my dad if there was a heaven. We had started to take a break from going to church on Sunday—which would end up lasting about three years, until we moved back into a development outside of town in a ranch style house. I wanted something real from my father that I could remember and think of when the black hole would come at night and ask me questions.

“Dad, do you think there’s a heaven, and a God, and everything?” He looked down at me, taking longer than I had expected, which made me wonder what it was that I wanted him to answer.

“Truthfully, I don’t know, Ab. It might just all be something people make up so they don’t feel scared about what happens.”

I was eight, and wanted to ask him what does happen, but I knew the answer was that no one knew, and that’s why people can believe in a heaven.

Ilook out the lab window again, wondering if I could just dump my pile of flies out, but it would be about the same as dropping them one by one in the acid. They would freeze in minutes, especially since they can’t move. So I quickly take my pliers and drop them in two or three at a time. When they are all in there, lifeless and floating, I dump the dish in the trashcan with the others, grab my books, and walk on to second period. It doesn’t matter anymore what color their eyes were, if they had purple wings, were special.

They are a finished generation.

There’s a foundation called the Near Death Experience Research Foundation, abbreviated NDERF. They take testimony from people who almost died and came back to life, to try to prove that there is an afterlife that is familiar and beautiful. I try to take their website seriously—it’s run by two married scientists, Jody A. and Jeffery Long M.D.—but the site’s text is all blue and green. I thought science was supposed to be black and white.

In some of the stories, the survivors say they were traveling through a tunnel, full of music and colors. They felt good about themselves, safe. These stories are all meant to make us feel better; but I wonder if anyone ever almost died and saw the fires of Hell, got her eyelashes singed as she pulled back from the devil’s scaly fingers, only to wake up on a hospital gurney with two wide-eyed nurses and a med student holding a defibrillator.

They don’t include those stories on the NDERF website.

If you click on, “What it feels like to die,” you’ll see a page that says that we continue to exist after death; we just lose our bodies: “slough off and discard the jacket you once wore.” I think back to the cat I dissected organ by organ and his little jacket of skin. Without it he didn’t even look like a cat anymore. I took it off and all that was left was muscle, meat, and some cat food we found in his bowels. Across the table from me another group found some half-digested floral paper towel in theirs. There wasn’t anything else.

If the body is the jacket, I worry that when it’s taken off, what’s left goes walking where there’s wind, and shivers.

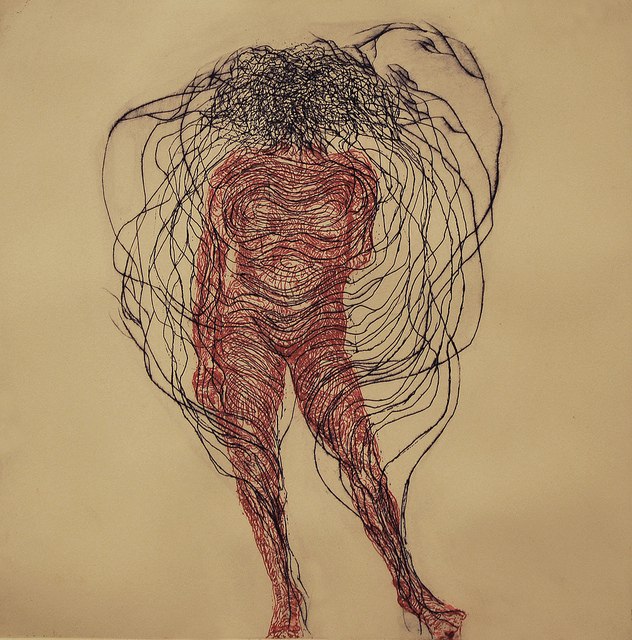

About the Artist

Marielle Saums, Carnegie Mellon University

A native of Washington, D.C., Marielle Saums is a senior majoring in global studies with minors in biological sciences and fine art. Marielle is constantly finding new ways to combine her interests in ecology, printmaking, Latin American history, and cooking.

No Comments