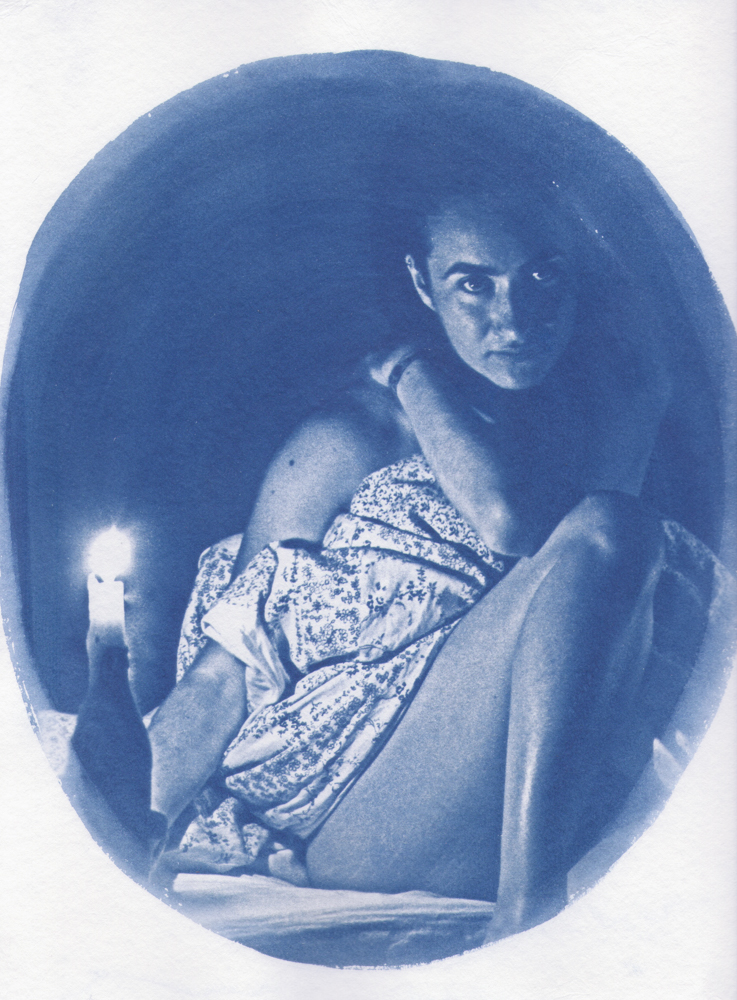

Karla with Candle, Kreuzberg, Berlin, Samantha Metzner

When I was in fifth grade, I asked my mom if I could start shaving my legs. There was no real need for this—I was both blonde and prepubescent, for Chrissake—but the question had been bothering me since earlier that day when Courtney McArthur started bragging about how she shaved hers. In the spirit of middle-school insecurity, this sparked a witch hunt to find out who shaved their legs and who did not. Thankfully, the conversation never got to me, but I was fully prepared to lie. At the ripe age of ten, Courtney was already a mean-spirited little gremlin that I was not equipped to handle.

Perhaps it wasn’t fair of me to jump my mom with this question right after she picked me up from school, but I had long since learned that using the element of surprise was the best way to achieve a “yes” where Jerilyn was concerned. She was, in fact, taken off-guard but answered with the neutral: “Okay, but not above the knee.” I nodded in agreement, then went to town hacking at my calf, thigh, and arm hair in the shower that night. I rubbed a hand over my skin, marveling in the smoothness, until my older sister Katie walked by and informed me, “You know it grows back thicker and darker every time you shave.”

I was instantly thrown into a panic. Was this true? Had I just cursed myself to suffer jet-black arm hair for the rest of my life? It had seemed like a good idea at the time, but had I just committed the rest of my life to this time-suck of a routine? Did I even have a choice anymore, or was I already doomed to become a hairy monster? I cursed the hubris of youth.

The social implications are clear enough, but I do wonder what Jerilyn’s first thought was. I think it must have made her a little sad that a child could already be invested in beauty standards. Or maybe it had seemed like the natural time anyway. Maybe she had been two months away from foisting a razor at me and saying, “Get it off.” Either way I’m sure it wasn’t what she was expecting to hear when I climbed into the Pacifica that Monday afternoon. And for good reason—up until then most of my attention was focused on drawing bad manga and my saxophone lessons, but the tide was changing.

If you’re thinking that this sparked a healthy dialogue between Jerilyn and I, one in which I felt free and eager to express my bodily concerns and in return she coached me through this tumultuous time with the all-encompassing wisdom and grace that only a mother can possess, you would be wrong. Not to put the blame entirely on her shoulders. Our family is a bunch of tight-lipped Irish Catholics (except for my father Mark, who’s a Lutheran hippie by comparison), and nothing—not even baby Sarah’s beauty crisis—was going to change that. My reluctance to discuss the matter was matched only by Jerilyn’s reluctance to listen.

This fact became readily more apparent to me as I progressed into adulthood. One day after gym class I sat down on the toilet and something caught my eye, which is never a great way to start a bathroom experience. The stain was a rusty-brown color, and for a second I just stared with complete bafflement. It looked like melted chocolate if we’re being completely honest, and I was puzzling over when and why I had shoved a candy bar down my pants. Then suddenly it hit me.

At first it was shock, followed immediately by indignity as I realized how little I actually knew about this. Melted chocolate? Jesus Christ, Sarah. Get it together. But what knowledge could I actually apply to the situation? After fighting off the initial panic, I eventually settled on the oldest trick in the book—crumpled toilet paper—and waddled self-consciously to class. The first person I told was my friend Kayla, who was known for being the “mature” one of our friend group. This was measured by the fact that she wore a real bra, already used tampons, and had a boyfriend who she made out with at the top of the ferris wheel during the county fair that summer. All of these traits qualified her to be my confidant. When I told her, she gave me a hug and asked, “Feel like a woman?” Decidedly not.

My mother, bless her heart, had not prepared me for this period shit. Part of me wants to know what her plan was, or if she even had one. I guess she put too much faith in our junior high sexual education program, which consisted of a fifty minute video once a year. In fifth grade they—at this point everyone in an administrative position was lumped together with this unspecific pronoun—separated us with boys in one room and girls in another. This particular video was period-intensive. I remember staring at an animated diagram vaguely resembling the Texas Longhorns logo, trying to figure out what the fuck was going on. The actual science behind what a period is and why it happens was never explained, but I can’t say it would have made a difference.

At the end of it, when we were all steadily avoiding eye contact, we were given “period packs.” They consisted of a travel-sized deodorant and a handful of pads as well as a pamphlet or two which I’m sure nobody read. I remember tittering nervously as we clutched these packages, doing our best to conceal their loud pink print as we stuffed them in our book bags. Perhaps if I had taken a moment to do some light reading (the pamphlet entitled “Period Party” looked promising) I wouldn’t have immediately assumed my crotch had melted a Hershey’s bar when it finally happened.

In sixth grade the boys and girls were lumped together to watch another video, and this one was intercourse intensive. Everyone knew it was coming and, being wise to their tricks by now, people started to question what would happen if you just skipped the sex ed day. Like, what could they really do? The answer was as follows: if you miss the in-class showing then you will have to take the video home and watch it with your parents. The sheer notion of being wedged between Mark and Jerilyn on our couch while learning how an egg becomes an embryo was so horrific that I could’ve had any ailment, anything at all, and still found a way to be in class that day.

The couple in the video were named Chad and Abby, and I remember being endlessly relieved that my parents had made the choices they did when naming me, because the only thing that would’ve made the experience more awkward was hearing about how Sarah and Chad’s love for each other made it okay to do these things (they weren’t even married, so in retrospect it presented a relatively liberal standard for procreation).

Once past these initial hurdles into adulthood, however, it was smooth sailing—for about a year, that is. Having shiny smooth legs—Katie had successfully scared me away from fucking with my arms—seemed to satisfy my body image and, being a scraggly child from the get-go, I was never overly concerned with my weight. That is until Brenda, the (probably) well-meaning mother of my friend, decided to shake things up when she announced, while serving us over post-sleepover donuts, “You’ve got a fast metabolism, girl. But just wait until it slows down. Things are gonna change.” This was followed by an overdramatic shudder and a pointed glance at my second Bavarian bismarck, already half gone.

When I got home I booted up the internet and waited impatiently for two minutes while the definition of “metabolism” loaded. The definition—the chemical processes that occur within a living organism in order to maintain life—didn’t shed much light on the situation, but through context clues I was able to piece together that having a fast metabolism meant that you stayed thin and without it, obesity was inevitable.

What the situation called for was an examination of Brenda’s own issues that caused her to say that to a girl in penguin pajamas, but instead my brain went straight to the question of: is this what I had to look forward to? Adolescence hadn’t exactly been a cake walk up to this point, and the teen years weren’t looking much brighter. I suppose I should be thankful that my immediate response to this crisis was just to bury it in cynicism and focus on marching band practice, because squawking out a Grease medley on the sax might’ve been the only thing keeping a dangerous spiral at bay.

When I tattled about Brenda to my mother she just blinked and shook her head before turning back to her Martha Grimes novel. At the time I was disappointed—I had honestly been pining for a bigger reaction. But my brain rationalized that perhaps Jerilyn wasn’t angry because she recognized Brenda as someone who got stuck in adolescence, who never found a way to shake the insecurities that root themselves in us at such a young age. And perhaps that lack of a reaction was a reflection of the fact she herself had moved on, and people like Brenda didn’t bother her anymore. And perhaps it was also a testament to her faith in me, that she trusted me not to fall victim to the same thing.

Or maybe she just thought Brenda was a bitch and had seen this coming a mile away. Either way, I didn’t stop eating donuts.

About the Author

Sarah Mueller · Loras College

Sarah Mueller graduated from Loras College in May 2019 with a degree in Creative Writing and Media Studies. Both “Not Above the Knee” and “Sticky Air” first appeared in The Limestone Review. She has also had work published in The New Plains Review.

About the Artist

Samantha Metzner

Samantha Metzner is an artist currently based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She works primarily with alternative photographic processes and relishes in the forever rewarding qualities of handmade photographs. Her images come from places she’s visited and people she’s seen. “Karla With Candle” first appeared in Adroit.

No Comments