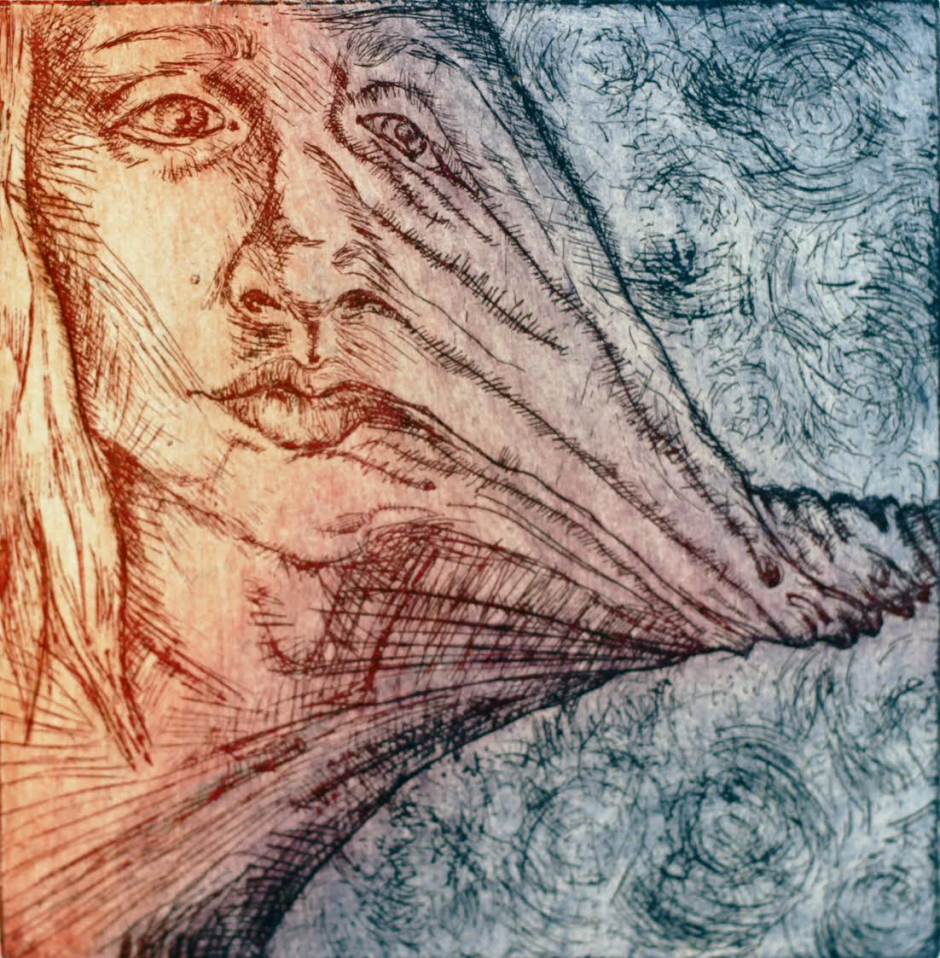

Wrung Out, Kaitlyn Kugler

It is my thirteenth birthday. At the lunch table I sit facing my friends with a ten calorie bite of vanilla cake marinating on my tongue. Amylase is breaking down the microscopic sugars, sending them sizzling down my gullet where peristaltic movements smush and squeeze them into my stomach. I feel pangs in my chest, and I recognize the hydrochloric acid and pepsin dissolving my food. I am at the lunch table, and a ten calorie bite of vanilla cake is almost too much to handle. I know where it goes. I can point to any locus on my body and trace it to a moment of weakness: the subcutaneous lump where my arm touches my breast is a raspberry jam sandwich on white bread, the protrusion of my hips a manifestation of 80% lean (20% fat) ground beef. It is my thirteenth birthday, and I have been cold for six months.

I am thirteen-and-a-half and I take deep breaths when I stand alone in the kitchen at night. I cut up an apple into twelve pieces (72) for tomorrow’s breakfast. For lunch I fill a plastic Tupperware container with twenty grapes (32), and I glue two rice cakes (60) together with one tablespoon of peanut butter (90). Dinner will be another apple (72). I am thirteen-and-a-half and tomorrow I will equal 326 and my guts will glisten squeaky-clean like my report card.

I am fourteen and the clinic hallways are too bright. Splashes of neon stain the inside of my eyelids when they close. The ceilings are swirls of cerulean and phthalo blue; the backs of turtles peek out between the waves. Fish with silver scales and glistening eyes swim freely above our heads. Nobody looks up in the hospital. I am fourteen and I focus on the white and black dots that speckle the linoleum. The woman on a couch across the waiting room is busy swiping on her phone, busy pretending that her son isn’t the only bald boy in kindergarten. I listen to the noise her bald son is making as he reads a picture book aloud, the way it slices through the silence that my parents cast my way. The air is heavy and still. I am fourteen, and I am not supposed to be here.

I am fourteen and I trail behind my nurse as she waddles down the hallway to the corner where I will remove my shoes, step up onto the scale, and succumb to the numbers that have never made sense to my food-clogged brain. I pick a giraffe on my nurse’s scrubs to stare at, praying she can take the fucking hint but she can’t, and she announces my Number to the world. I am fourteen and my doctor leans forward in her chair with her ankles crossed. Her lips are thin slits and she smells musty, like someone who drinks too much coffee and not enough water. She asks me if I know that twenty percent of the energy I consume goes to powering my brain. I pick a speckle to stare at. There are no fish on the ceiling of this room. No, she scolds, 100 calories is not enough to power “what’s inside my thinkin’ cap.” I shake her hand, collect my new treatment plan, and try not to look at the floor.

I am fourteen-and-then-some and I pray for the courage to press down; my fingers tremble as they squeeze my soft stomach. I release the scissors, and a cherry lesion emerges from under each blade. I am leaking. Saccharine muscle fiber drips down the front of my thighs and smears my cinnamon-sugar insides. The girl at school with purple hair and rainboots that kiss her kneecaps tells me about the outpatient program she’s just completed. She reads to me her new notebook full of numbers (766, 912, 794, 1021…) and I show her my anthology of hospital bracelets—nine. She eats bologna and mustard sandwiches on white bread (??). I eat ten baby carrots (40) and one banana (95). I am fourteen-and-then-some and I don’t want my sticky syrup body.

I am fifteen, and I go to a new school, and I discover that my toothbrush fits perfectly in the back of my throat. Christmas is in three days and I sit on the couch in my grandparents’ living room, staring at the deer heads mounted to the walls. I’m imagining the angry blood that mats their fur and stains it red as my thirty-three relatives laugh in the wide, flat register of country-folk with freezers full of venison. I am so cold, but my cheeks burn hot when they talk about how strange it is that I cut my meal up into tens, hundreds, thousands of itty-bitty pieces that never bridge the gap between plate and digestive tract. They tell me they’re just making a joke, hey now, no need to get fussy. They pat my pudge and show me smiles that swallow their teeth. I am fifteen, and recovery is a lifeless word that seeps into the cracks of my chapped lips.

About the Author

Nadia Ravensborg · The George Washington University

Nadia Ravensborg is a Nutrition major at George Washington University. This piece first appeared in the University of Minnesota’s Ivory Tower.

About the Artist

Kaitlyn Kugler · University of Minnesota Twin Peaks

Kaitlyn Kugler is an Art and Psychology student at the University of Minnesota Twin Peaks. This piece first appeared in Ivory Tower.

No Comments