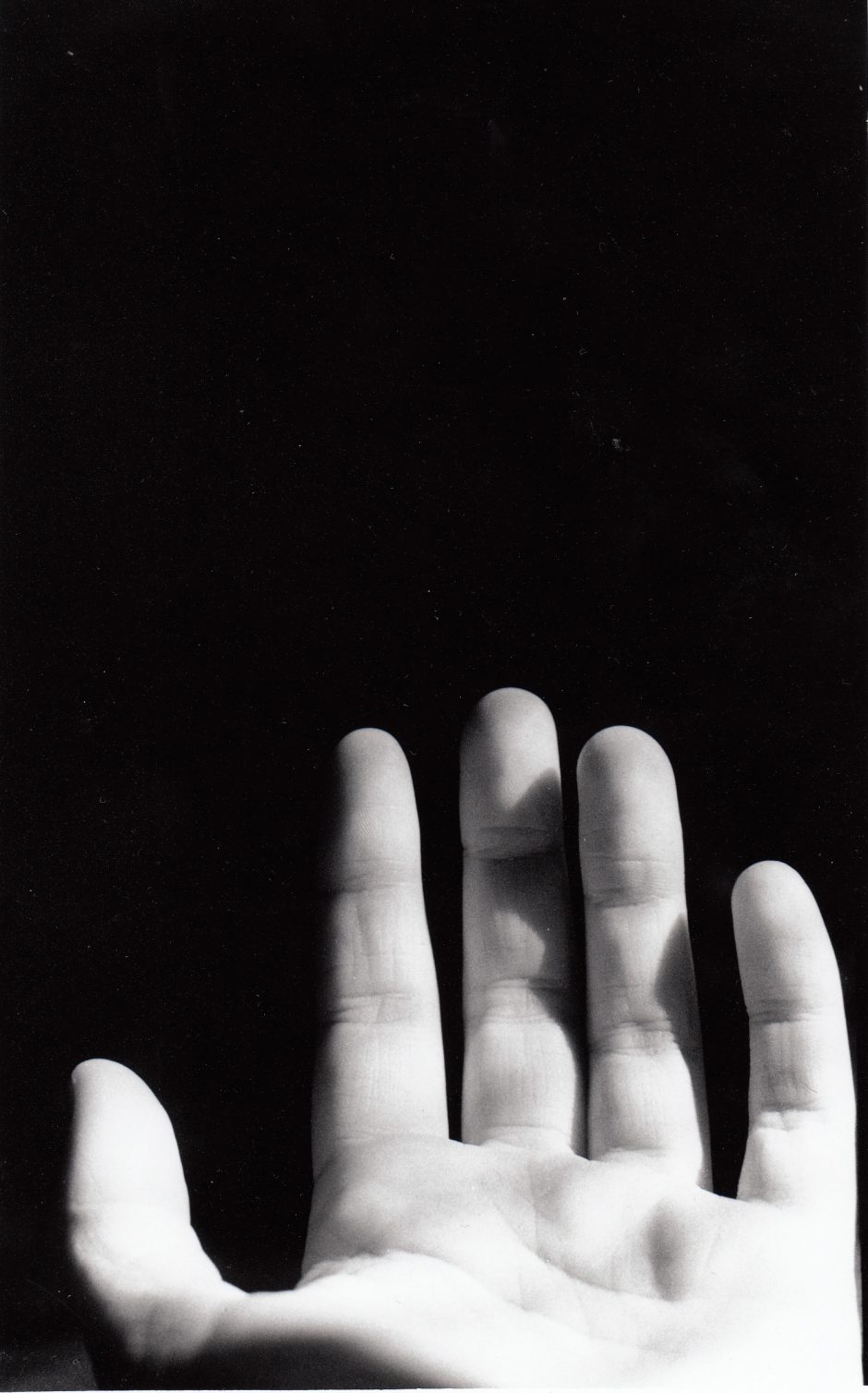

Hand, Kaitlyn Fitzgerald

[Trigger Warning: Brief mention of a stillbirth]Two bleary, beady eyes were regarding me steadfastly. The mass that framed them, the rounded head of the thing had, one might say, a face. There was a mouth under the eyes, the lip of which quivered and panted and dripped saliva. The whole creature squirmed and twitched convulsively. The peculiar fuzz covering its fine powdery skin, the incessant trembling of its awful gaping mouth, the clumsy deliberation of each breath, the rhythmic surge of its tiny chest – above all, the extraordinary gaze – at once vital, intense, crippled yet penetrating. At this first glimpse, I am overcome with apprehension and dread.

Then, wonder: a lifetime ago, I was once this creature.

With a shudder, I turn back to the shelves of pacifiers and striped pastel baby hats. Check. Fully-loaded cart “borrowed” from the janitors. Accompanied such, I make my rounds up and down the hallway of the maternity ward, stocking the cabinets for the nurses. Four poorly-folded blankets that I have to refold, as usual. The oft-overlooked miniature packs of isopropyl alcohol. No bottles of glucose today. The supply shelves are out of stock.

Finished with the shelves, I hear a buzz of dialogue near the front desk. “Excuse me,” I tap a nurse on the shoulder. “Do you need help wheeling a patient downstairs?” She nods with a tired, relieved smile, indicates a patient room, and rushes away. She is a god of the intravenous drip, and I am her Friday afternoon Hermes. Like her co-workers, she is always on the move, maternal figures for maternal figures. All the nurses buzz with the urgent energy of the too-much-to-do-in-too-little-time nature, marching in time to the beat of the cardiac monitors.

Some of the women I meet are round and bright with youth and excitement and love. Some are old enough to be my mother. Sometimes I chat with their overly-concerned male chauffeurs… the ones who speak English, at least. Then there are the mothers who take painful mincing steps to the wheelchair, exuding a silent ragged exhaustion. They carry their babies in their laps methodically, almost woodenly. All of the women sit quietly on the wheelchair as we take the elevator plunge down. 6… 5… 4… 3… 2… 1… The floor level numbers flash like warning signs in the poignant silence, heavy as mother’s milk. In the pensive stillness I see what they see – that in the relentless elevator descent of time, someday their babies won’t be babies anymore.

The nauseating smell of Enfamil pervades the nursery. My senses drown in talcum powder. Next to the door, a rocking chair sways to the clock. Tick. Tick. Tick. I pretend the rocking chair is a boat sailing away from the island of Sixth Floor and its offensive odor. I fancy myself a passenger… but then I notice the nurse on the chair holding It. I change my mind.

It’s atrocious. Bruised, edematous, and tainted with dried blood.

A nurse stands up and asks, “Would you like to hold the baby?”

Somehow I end up with it. It’s heavier than I thought it would be.

“There you go! Honey, you’re a natural!”

She kindly lies.

“Here, honey, just set the towel on your shoulder like this. It’s there to protect your shoulder from… well, you know. Sit down on the rocking chair – it’s a lot more comfortable.”

I comply.

“Alright, now you’ve just got to rub the baby’s back and get its circulation going… Give it a couple good, solid pats so it can get the air out. Great!”

The nurse lingers for a moment.

“This one’s pretty lucky. It was a breech delivery, you know. The doctors had quite a tough time… We just had another stillbirth today, too,” she pauses for a moment, then shrugs. Business as usual. “Anyways, you can put the baby back in the crib after twenty minutes or so.” She points to an advanced Tupper-ware container lined with a pastel blanket.

I am left alone with it, which stares at me. I gingerly rub its back.

I’m not sure why I kept coming back.

No Comments