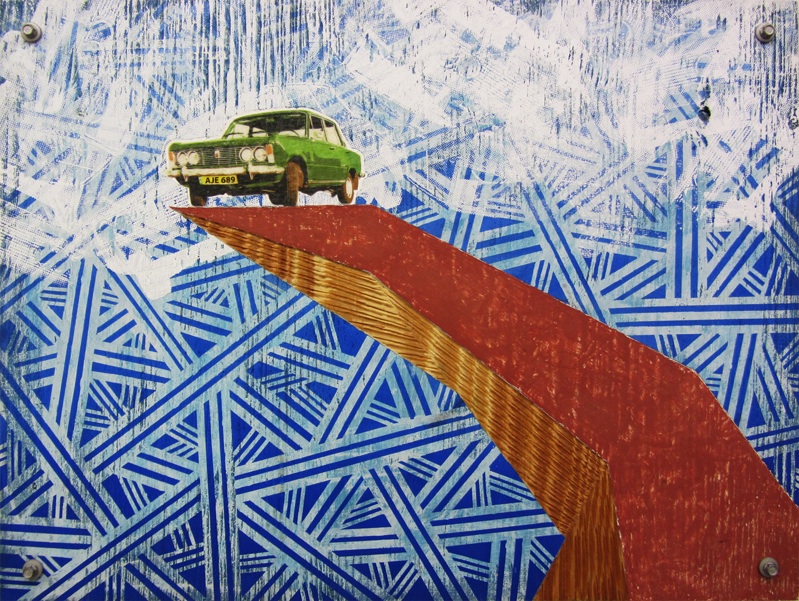

Polski 125, David Diaz

They made this Mustang in 1968 and called it a 1969 Fastback. It had none of the special options packaged with it—it was not a Boss, not a Mach I. It was meant to go to a man of humble means, someone who knew how to have fun but didn’t need the whole town noticing, so it had a 302 engine that hummed with a two-barrel carb and was painted in understated Lime Gold. By the end of the year it was tearing down country roads in south Alabama, gravel banging up its rock deflector and blasting away little chips of paint so that the car looked still-photographed, forever sparkling in the hot humid sun.

Donnie wasn’t more than nineteen when he bought it. He still lived with his parents and had been saving money in tight rolls of hundreds in a spittoon under his bed. He had been working at Gilman’s Lumber since he was fourteen years old. Sometimes Donnie’s plastered, totally shit-faced dog-eyed drunk father tried to break his son’s downhill speed record of 109 mph on the only paved road in town while Donnie sat in the passenger seat screaming and spraying whiskey-soaked spittle all over his cheeks and onto the headrest. Sometimes the driver was Donnie, taking turns too quickly in the dark night with only the dims on while his girl yanked at his belt and he burned down a joint and his eyes turned to fire and his nerves crackled with electricity.

Donnie was struggling in the confined space of the back of the car to pull his pants up, his head against the rear windshield and his ass between the front seats. The Mustang was parked alongside a barn on her parents’ property. They had cut the ignition off at the road and turned in and coasted into place some forty yards from the trailer where her parents slept. His girl was sitting longwise on the rear bench, sliding her panties up under her skirt. She began to laugh at the sight of him, a long loping laugh made so by the alcohol buzz she felt behind her eyes.

My parents will see your white ass, even from way out here. Set down.

Goddammit, hold your horses.

He got his britches in place and, nudging her feet aside, sat down. He put his feet up on the center console, and she put her legs across his. The air was musky, hot. Smelt of flesh and fluid. She ran her hand down her nose, wiping the oil away. She twisted the latch and pushed open the back window, a small triangle of glass rotating at the middle. The outside air streamed in cool across her cheeks like from some other corner of the world. The honeysuckle was coming in.

When are you gonna move in with me?

She flinched, coming out of her reverie. She looked over at him. He was staring at her legs, his hand cupping the inside of her knee. He looked over at her.

You’ve been eighteen for a while now. It’s what we talked about, ain’t it?

Yeah, we did.

You mean you don’t wanna?

That ain’t what I mean.

It isn’t?

No.

Well then, what?

Her skin was growing accustomed to the outside air and it no longer felt cool against her face. She stuck her fingers through the window, waved them at the blackjack on the hill beside her house.

You live at home, she said. Why would I trade my parents for somebody else’s?

Cause I’m gonna inherit that tract. It’ll be ours. We can just get another trailer and put it on the lot for the time being. Won’t even be like we live with him.

It’s still just living with your dad.

Well, what’s wrong with that?

Nothing for you, I don’t reckon.

You act like there’s something supposed to be wrong with it.

Donnie’s girl just shook her head and looked away.

You worried he’ll interfere? I guaran-fuckin-tee you my diddy won’t interfere with nothing but what gets between him and his sixpack. Donnie began to laugh, nudging her with his elbow.

I’m worried nobody wants a drunk for a paw-paw. You thought about that?

Ain’t nothing to think about, cause that ain’t nothing yet. You’ve been late before.

You ever think about anything except what’s staring you right in the face? It won’t look away just because you do. She looked at him. When it’s time enough to know, we’ll need to of made a decision. If we have a kid it’s not gonna grow up in this place.

Donnie sat up straighter. What’s wrong with this place?

A baby can’t grow up here. We ain’t been nothing but poor.

Poor? Baby, look what you’re setting in.

My family’s been here generations. All that work, all that time. Just a trailer and a useless barn.

Then his shoulders slouched and his gaze grew less certain, softer, wavering.

You do know that, don’t you? Donnie, you know a baby can’t grow up here.

A pause.

Don’t you think I know that?

You ain’t acting like you know that.

Donnie clicked his tongue and looked away and pulled his hand off her leg.

Well, I gotta shit, he said. He pushed the driver’s seat forward and started to climb out.

You’re not going inside.

Donnie laughed humorlessly and got out.

You’re not going inside, she repeated.

Where else am I going to shit, baby?

Anywhere but inside. They’ll hear you. Footsteps carry.

Then I’ll be quiet.

Donnie, don’t.

Donnie scoffed and threw up his hands. Just for once let it be, he said. Just let it be.

He closed the door and set off across the grass.

Donnie’s girl climbed into the driver’s seat, her eyes on her parents’ bedroom window. She waited, moved the shifter into neutral and jiggled it back and forth. She tried to make herself stop, but couldn’t. Tried to stop the fiddling, tried to stop the crying. Neither worked.

She looked up at the broadside of the trailer. Sheetmetal walls painted blue. She pulled the headlight knob all the way out, then opened the door and dropped Donnie’s shoes onto the grass. She twisted the key in the ignition and the car opened up and the headlights came on, a bright pair of white eyes staring into her home and filling her parents’ bedroom. Her dad rose up out of bed, his wifebeater glowing and every hair alight. He turned to look at her, but immediately closed his eyes again as if trying to stare an angel in the face with all its terrible beauty. Her parents ran from the room and the hall light came on as she slammed it into reverse.

The traction-locked tires caught in the clay drive and sent her out into the country road. Then her father was out in the front yard looking at the ruts in the drive and the alluvial spray of sediment. Her mother came running out a moment later, grabbing at her ponytail that had begun to fall loose around her shoulders.

She’s not in her room, Ernest.

That car belongs to the Hale boy. I’d recognize it anywhere.

Donnie stumbled out the door a second later trying to pull up his pants and buckle his belt at the same time. Her parents looked at him.

Hmm. I didn’t know she could drive a stick, said Ernest.

Her mother said dear, dear and her father said that if the circumstances were different he’d have been madder than hell at Donnie for fooling around with his daughter. Her father went back inside to call the sheriff and her mother followed. Donnie leaned up against the doorframe with his jeans around his thighs and the aluminum post chilled him through his boxers.

The day before Donnie’s girl used the Mustang to run away, Donnie and his father had gone through the genealogy box.

These are your Grandaddy Boo’s teeth, Claudie Grover, Donnie’s father, had said.

He’d put a small pouch in Donnie’s hands, told him to feel the teeth. Donnie had moved to dump them into his palm but his father said no, said the oils of his hand would deteriorate them, cause them to turn to powder in the bottom of the tiny parchment sack. Donnie felt them through the pouch, felt the knots in their contours, their roots. The shape they made through the fabric. Like one world subducting another, leaving bonemeal traces.

His father was shifting papers around in the box, picking up stacks by the edges like they were as fragile as dried and pressed flowers. He moved a postcard and Donnie saw a few strands of dark hair tied together with a bit of lace. What’s that? he asked. His father picked up the lace, rolled it in his fingers. The hair tickling his knuckles. He said he didn’t remember who it belonged to.

The box’s seams were beginning to fall apart. A bracket on one of the bottom corners had busted into two chevrons of oxidized metal. The ends curling away into rust debris. The wood of the box was fractured into ribbon-shaped slats barely held together. The metal of the latch felt grainy to the touch, like a sanding stone nearing dissolution. Within there were title deeds, letters, a swatch of sky-blue linen cloth, photographs, a violin bow. A fedora, the lining eaten away, the felt hardened like maché. A grandfather played the fiddle. A great-great-grandfather wore a red-striped kepi. Their names memorized by a dutiful son at his father’s insistence.

This is your blood, your kin, his father had said. You’ve got to remember that.

I know, Diddy.

I won’t be around forever to remember for you. A dead man don’t remember nothing.

Donnie had forced a laugh, but his father had not joined in.

The leather of the seat was cold beneath her thighs and it smelled of earth. The pads on the floor were brown from the clay and sand that had been pressed into them by young people who never kicked the running-boards to clean their shoes before jumping in. She bounced her knee while the heater warmed up. She had taken the car because she knew this way she’d get Donnie to meet her somewhere far away, maybe Montgomery or Albany; she didn’t know which way she wanted to go yet. She up-shifted and hit the highway and drafted behind a semi drifting across the center line, its driver probably fighting to stay awake until he hit Dothan where a truck stop waited with quarter-fed showers and an all-night Whataburger. The tips of the Gilman logs on his trailer hung out over the ever-running asphalt, bouncing and swaying with every bump in the road and every tired drift of the driver. The logs were pine, distaff soft wood, narrow tips facing her down in a phalanx.

Donnie liked to think of his girl as helpless, wheel-less, without him. She had never wanted to disappoint him with the truth. In the morning she would call his house and yell a “Hello!” at his dad, who’d be drunk on the sofa. Alcohol made his father forget how to use the telephone, so whenever he was three sheets to the wind he shouted into the mouthpiece. Eventually he’d give her to Donnie, and she would tell Donnie where to meet her and at what time and which friend to hitch a ride from. She did not trust Jimmy Hutto, because he was a brownnoser and would tattle at the first chance, but Rory was always loyal to Donnie’s girl: he loved her sandy hair and the way it played spiders on his neck when she sat between him and Donnie in the front seat of this Mustang. Rory liked to love her, and now that was what she needed from him. It was a cruel thing, she said to herself, and then punched it and swung the car out into the other lane and began to overtake the drifting semi and the tired old man who captained it.

Donnie’s girl slid into the booth at the Whataburger with a paper cup of burnt coffee in one hand. With the other she drove her fingernails into her palm. The vinyl cushion against her back exhaled when she leaned into it and the bends of her knees stuck to the plastic seat. She had slept in the backseat of the car and felt like she had a dent in her skull from the edge of the interior quarter panel. She massaged the side of her head, felt the oil in her hair.

You want I could get you some more coffee, said a voice. She looked up. The cashier, a gangly boy with a thick knot in his throat that bobbed whenever she met his eyes, stood beside her table.

I got all the burnt coffee I need right here, thank you, she said, and lifted her cup a bit.

The cashier blinked his large blue eyes. He adjusted his paper hat and it made a faint crackling sound beneath his fingers. At least it’s hot, he offered.

Donnie’s girl sort of said mm-hmm and the cashier walked away with his shoulders hung and went and stood behind the register.

When he and Rory pulled into the lot, Donnie made a beeline for his Mustang and stuck his head in the open passenger window. Rory saw Donnie’s girl sitting facing them and gave a little wave.

Baby, what are you doing? Donnie asked.

Sitting drinking, she said.

You took my car. Do you even know how to drive it?

I got here, didn’t I?

Donnie sat down across from her. He blinked fast. Where did you stay?

Same place I drove.

Wait, don’t you realize how—how dangerous that is, baby? What if someone was to of come up on you in the night or was to of stole my car, or worse?

Wouldn’t that be a crying shame.

Donnie clicked his tongue. Baby, you know what I mean. Why are you doing this?

She bit her lip and her eyes moved away past him. Rory was leaning against the Mustang, moving the toes of his shoes across the ground in front of him. You think if we live long enough, we’ll get tired of fighting? she asked.

We’re not fighting. Why can’t you just let this go? Come home.

Because I’m not sure what’s happened. I’m not sure what this is.

What what is? Baby, I’m sorry, this is stupid. I mean, what in the hell. Rory’s out yonder. Let’s just go. I don’t even know why you’re worrying—it’s too soon to know. It’s not time to worry yet.

There was a metallic tinkling sound and they both looked up. A man with a bristled day-old beard walked in the side entrance. Donnie’s girl watched him approach the registers and she caught the cashier looking at her. She blinked at him. He tried to ask a question with his eyes, with the distant concern of a stranger. She wanted to tell him she was okay but did not know how to say such a thing.

When is it time to worry, Donnie?

Not now.

Not now?

No.

That’s not good enough. I need to know when. Tell me when.

Donnie held his face in his hands. When did you stop loving me?

Donnie.

What.

Don’t say that.

I need to know that. Tell me that.

I love you, Donnie.

If you don’t love my diddy you don’t love me.

It ain’t that simple.

Yes it is, baby.

Then why would I try and take you with me?

In 1973 Donnie’s girl had a baby and the clutch on the Mustang gave out. Donnie dropped it at a junkyard for a hundred dollars and they boarded a bus to Birmingham that same hour, headed to her aunt and uncle’s house. It was five o’clock. Donnie’s father, by this time, was in such a state that his only memory would be the ache that lingered between his brain and his eyes. He would shuffle through the house in the coming morning, his toes scrunching into the shag carpet, squinting at the kitchen where the morning light shone in on the yellow linoleum and off the fridge’s door, looking for his son.

I could tell you her name, but Donnie’s family does not remember it. Not in their stories, not in their genealogies. There is no Ziplock bag containing three strands of her sandy hair or a cutting of her linen blouse. If I told you what Donnie’s girl was called, something would be changed in the memories of this Mustang and in the way the blood-stories cut into its steel and get sunk in. Somewhere, perhaps between the carpet and the kickpanels, is a lie like a knot in the fabric. And if you teased it open, pulled it out and looked at it, you might unravel the whole thing.

Their story became about a boy setting out and starting a family in some new place, a wife and a child in tow, pulling up roots. They will tell the blood of their blood that he was brave. That he did what needed to be done. That leaving is hard.

No Comments