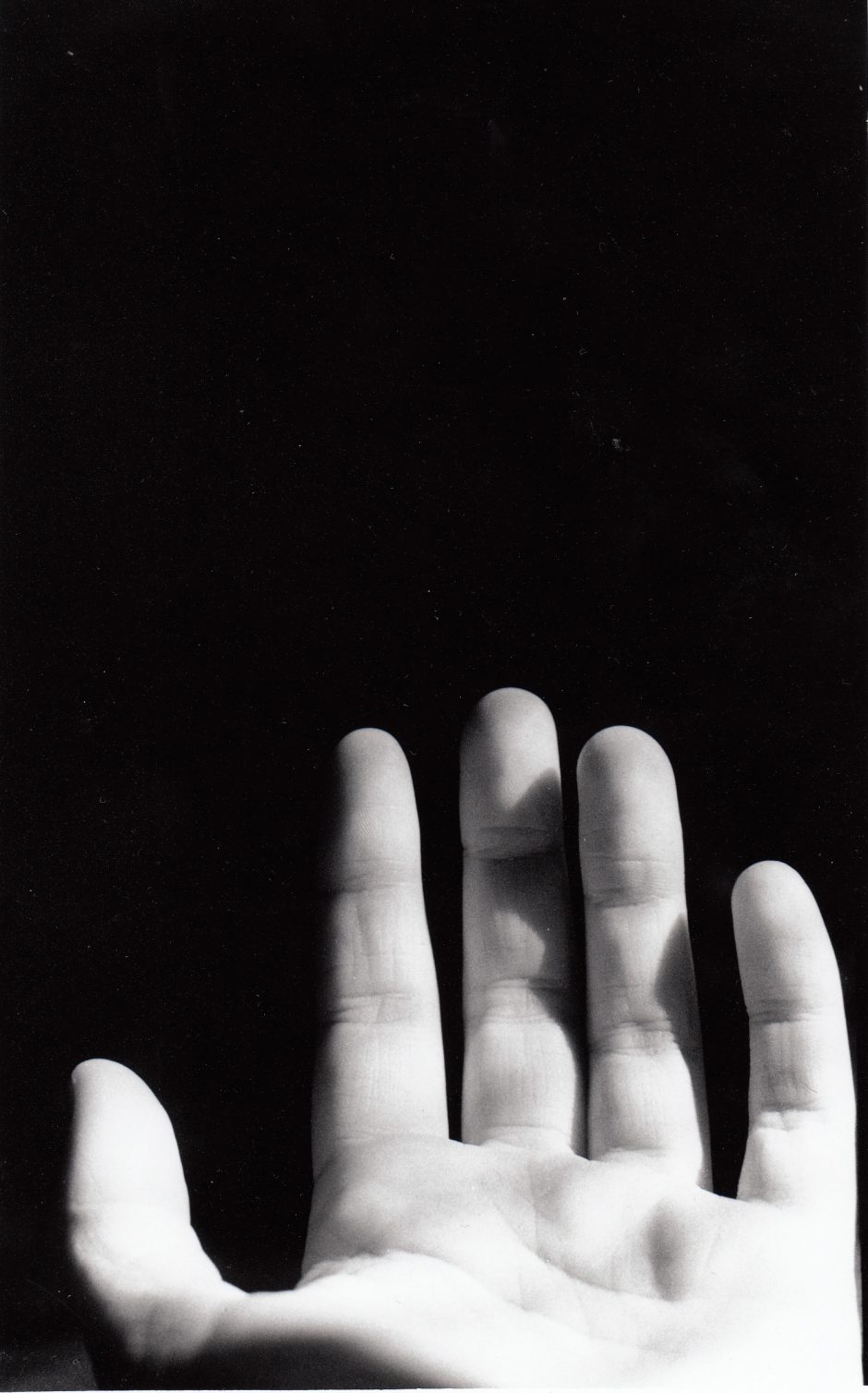

Hand, Kaitlyn Fitzgerald

“I don’t like Bach,” I complained, lowering my bow. I was fourteen and feeling contrary.

My teacher Jeannie, seated at the piano, turned slowly to look at me over the top of her glasses. She drew her face into a look of comic horror. “No student of mine has ever said that,” she said. “Why would you not like poor Mr. Bach?”

“He’s stuffy and mathematical,” I said. “He doesn’t have any fire.”

Jeannie’s eyebrows dropped in understanding. “You prefer the romantic composers.”

I shook my head firmly. “They don’t make any sense. There’s no pattern to them.”

“Well, then, what do you like?”

My fingers fidgeted reflexively over the strings, silently playing Concerto in A Minor, the first movement. “Vivaldi.”

*

The day Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born, in March 1678, Venice was shaken by an earthquake. The Vivaldi family had the infant baptized immediately by the midwife, perhaps because of the ill portent, perhaps because the child’s lungs were not strong, and they thought he might not live. Some historians claim his mother promised him to the church then and there. One can imagine that his father, a professional violinist, was disappointed that his son would belong to God rather than the muses, though it wouldn’t stop him from trying to convert the boy to his profession.

*

I don’t remember deciding to play the violin. The story goes that my mother was singing in a concert at the oldest church in town. It was a big concert, with full choir and an orchestra, including a violinist.

I don’t know where I was sitting, but I imagine it was up in the balcony, the one that has stood for three hundred years but always seems about to give way under my feet. I imagine myself leaning out over the railing as far as I could, staring at the violinist, wide-eyed at the beautiful sound.

At age six, it couldn’t have been the first time I heard a violin. It’s such a common instrument, and my parents listened to a lot of classical music. I must have heard one somewhere. But the story goes that this was the moment I fell in love with the violin.

On the way home, I’m told I announced my desire to learn to play.

“Why the violin, honey?” Mom asked. “Why not the piano?”

“The violin has a full, rich tone,” I said firmly. How a six year old knew what a “full, rich tone” was is a family mystery. My parents were floored. I began lessons just after my seventh birthday.

*

Although Antonio’s father was a professional violinist, he would have known—and taught his son—a wide variety of instruments. From an early age, however, Antonio suffered from a shortness of breath that made it impossible for him to master any wind instrument. The piano had yet to be invented, but he no doubt learned the harpsichord, which would later provide such plucky accompaniment for his violin concertos.

A full size violin is too large an instrument for a young boy to play, but many smaller violins were made during the late Renaissance and early Baroque period. Pitched a fourth above regular violins, they were to the adult violin what a boy soprano is to an adult voice. Perhaps one of these violins was found for the young Antonio.

I like to imagine him climbing out onto his roof at night to watch the sky reflected in the canals. The smooth water is disrupted by a solitary gondolier making his way home. Antonio bends over his tiny violin, long red hair flopping into his eyes. Fingers move over the strings, creating his first melody.

*

One birthday or another, my aunt gave me a CD-shaped present. I wouldn’t admit it, but I’d been hoping for a book, not another album of classical music. Not that I disliked classical music—classical music was my jam, mostly because there wasn’t a cooler style of music I actually did like.

I carefully tore off the paper. Vivaldi’s Ring of Mystery. I tried not to let my disappointment show. At least the cover was interesting: a man in a little violin-shaped boat punting through purple water.

“It’s a story,” my aunt explained. “Like a play, but it’s also got music by classical composers that fits with the story. Like a soundtrack.”

“Oh,” I said, trying to sound enthusiastic. “That’s cool.”

Days later, I slid Vivaldi’s Ring of Mystery into my player. Soft waves sounded. Violins started to play a tune that was vaguely familiar. Da-dun-dun-dun daba-dum…

Turning the CD case over, I read, 1. The Four Seasons, Spring I, Rv 269. Whatever that meant. Then a woman started talking, telling the story of an orphan girl in Venice a long time ago. Other actors came on: girls from the orphanage, a friendly gondolier, even the composer Antonio Vivaldi himself. There was action and adventure and a heroine with a mysterious past. I was enthralled—more by the story than the music.

Then, when all the girls were in bed, one girl started playing her violin, slow and sweet. It was the saddest thing I’d ever heard. I looked down at the box, which I was still holding in my hands. “Violin Concerto in A Minor, II, Rv 356.”

For the second time, I fell in love.

I had to know how to play that music. I ran to get all of my music books and flipped through them, hoping I’d get lucky. Opening the most advanced book I had, I saw, Concerto in A Minor, 1st Movement, A. Vivaldi. It was the third piece from the end of the book, well beyond anything I had played so far.

First movement, not the second—it was the one that had played when the heroine arrived at the orphanage, not the one I was listening to now. But it was better than nothing.

I got stuck halfway down the first page; the music on the CD didn’t play the whole thing and I got lost in the notes after I was on my own.

I took the book to my teacher. “I want to play this,” I said.

“That’s a little advanced for you yet.”

I picked up my violin and played the opening three lines, tossing the notes up into the air. Eventually, I ran out of familiar notes. My fingers fumbled and I stopped. “I want to play this one,” I repeated.

*

Learning the violin in the 1680s was completely different from today. Violins as a common instrument had only been around for a little over a hundred years. Stradivarius was just beginning to create the violins that would refine the instrument into its modern form. The chin and shoulder rests that allow the violin to be held securely without the use of the hands had yet to be invented, making each shift into a higher fingering position a juggling act.

In those days, there would have been no set curriculum for students, no proper way for Antonio to hold the instrument or draw the bow, no one but his father and his father’s friends to tell him he was doing it ‘wrong.’ A bare smattering of composers had even written popular music for the instrument. The capabilities of the violin had not even begun to be stretched. Vivaldi would be one of the musicians who stretched them.

What would young Antonio have learned to play? Did his fingers stumble over the notes to local Venetian dance tunes? Did he first try to mimic the old medieval chanting he heard in church, or was he born playing Corelli’s sonatas?

*

For my 15th birthday, I asked for copies of sheet music to The Four Seasons. The real things, I specified. Not the dumbed-down, transposed-into-an-easier-key versions I could already play.

I took Summer to my violin teacher that September. “I want to play this,” I said.

*

At fifteen, Antonio was already beginning his studies to become a priest. It would take him ten years before he was ordained. Within a year he had retired from saying Mass due to health complaints—although there is a story that these complaints were really just his need to get away and jot down a new melody he had thought of in the middle of Mass. Instead of being a practicing priest, Antonio was sent to teach music at the Ospedale della Pietà, a school for orphan girls and the illegitimate offspring of local nobility.

He began composing for his young students: orchestral and choral music, but mainly violin. Their fame grew, and so did Antonio’s. His red hair quickly earned him his nickname: il Prete Rosso. The Red Priest.

*

Late January. I’d been working on Summer for months, and I was finally going to play it at the end of term recital. The whole thing. All three movements. Six pages of teeny tiny notes. It was the biggest thing I’d ever done.

At my second-to last lesson, my teacher Jeannie listened to me play the whole concerto through once. She nodded happily through the first two movements. Most of the third. I made it through the double-stops on sheer nerve, then stumbled through the rapid progressions on the final page. I gritted my teeth. Why couldn’t I have been born with the long, clever fingers that violinists are supposed to have, that Vivaldi had had? Mine were always bumping into each other in their rush to get where I told them to go.

After I finished, Jeannie picked up her pencil. She drew brackets and an ‘x’ around five lines on page six. “I don’t think we have time to make this work,” she explained apologetically.

I went home. I pulled out my violin and I played the deleted section. Stumbled. Started over. Over. Over. I played the fingerings until I had pounded every ounce of sense or passion from them, until they were as cold and deadly mathematical as Bach. I practiced, hours each day, like I have not had the discipline to practice before or since.

Vivaldi’s music was mine, and I was going to play it whole, or not at all.

The next week, I returned for my final lesson before the recital. “I want to play the whole thing,” I said.

There is nothing as exhilarating as playing a series of difficult progressions on the violin. It gains momentum the longer it goes. There is no sight-reading the music; the notes go too fast for that. Instead, the fingerings are learned as a whole, memorized through muscle memory. One mistake can break the momentum and send the whole thing flying to pieces.

But my fingers leapt up and down the scales, and although they stumbled, they always seemed to stumble onto the right notes. I was in control of the music, at least for this one moment. One wrong finger, one wrong note, one misplaced shift in hand position, and it was all over.

I had fallen in love with the violin because of its beauty. I had fallen in love with Antonio because of his passion. Now I was falling in love a third time, falling in love with danger, with the maelstrom of music I could make.

Then it was over.

Jeannie took her hands reluctantly off the keyboard, breathing hard. She turned to me and speechlessly, solemnly shook my hand.

*

Only three portraits of Antonio are known to exist: an ink sketch from 1723, an engraving from 1725 that is almost identical, and one painted portrait from around the same time. In the portrait, Antonio holds a violin in one hand and a quill in the other. Rumpled pages of music sit on the table before him; he wears red robes. The obligatory white wig perched on his head covers all but a shadow of his eponymous red hair. Green eyes seem to look directly at the viewer.

His expression appears at first blandly kind, lips turned up in a small smile. Only after a while do you begin to see the firm set of his jaw, the confidence behind his direct gaze. Antonio’s grip on the quill is gentle, almost negligent. But his long fingers wrap possessively around the strings of his violin, poised as if reflexively fingering a melody.

###

No Comments