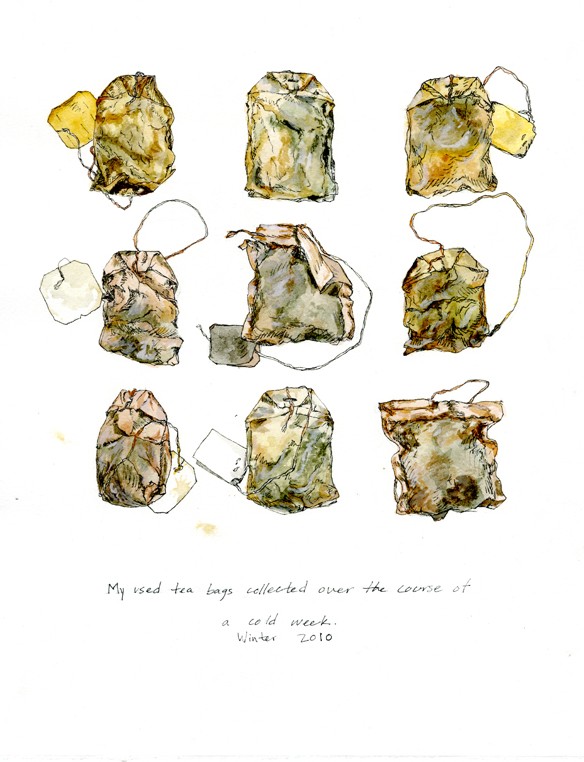

Used Tea Bags, Frances Lee

[Trigger Warning: Depictions of Mental Illness]The stove is on. I was taught in high school that brain cells are kind of like trees working in reverse. The information starts in the cell body, the bulk of the treetop. The stove is on. A message is sent down the tree trunk to the roots. The stove is on. The roots get the message, and release it into the ground for another tree’s roots to absorb. The stove is on. Serotonin, the message, is sent down a tree inside my head. The stove is on. There’s not enough serotonin, not enough of the message to relay. The stove is on. The heart starts to race, arteries expanding as if trying to water the tree so the correct message can pass through. The stove is on. Breathing quickens, panic taking over as the wrong message gets sent.

I need to turn the stove off.

The oven clock flashes 2:30 back at me. The bright light overhead forces me to squint; tears leak from the corners of my eyes. All lights on the stove are off; all the dials in the OFF position. For good measure, I turn them so the little line on the dial matches up with the number two, then quickly twist it back. I do this with all five knobs—four for the stovetop and one for the oven. All are off. I repeat another time for good measure. Two is always a good number.

After staring at the dials for a minute or two, convincing myself that I’m satisfied, confirming that all of them are actually off, I plod through my house, direct myself back into my room and climb into my bed. For a few blissful moments, my heavy eyes close and I sigh. The stove isn’t on anymore. I had made sure it was turned off. Hadn’t I? Yes, I had. I turned all the dials on, then back off, just to make sure. I checked, and double-checked.

But what if I didn’t? What if I overlooked one of the dials? Even if the dials were turned a fraction of an inch? My mind races as I lie there trying like hell to keep my eyes closed. It doesn’t work. Staring up at the ceiling, I break out in a nervous sweat, like I am cooking from the inside out. My sheets stick to me, and I only manage to tangle myself up more as I try to get free. My thoughts clatter around in my head with all the horrible things that are going happen if I can’t get out from the sheets chaining me to the bed and check right now. Images flash frantically, and my heart thuds up into my throat.

Flash. Images leak into my brain where the serotonin isn’t.

The house exploding as a mushroom cloud rises up to envelop the night sky in thick smoke.

Flash.

The body of my mother lying limply on her bed, one arm dangling off the side, while my father desperately grabs at the cherry red skin of his neck.

Flash.

My dog, Jake, curiously sticking his head into the open oven, passing out from the fumes, burning.

How would the oven door open? I don’t know. It’s not rational, and I know this. I was just in the kitchen and I didn’t even open the oven door. Yet it seems real, as if the images talk to me. You’re going to die, your family is going to die and it’s going to be all your fault! You left the stove on!You should go turn it off! Make sure it’s off, check and double-check. Keep checking until you’re certain. The whole neighborhood could blow up, all because you won’t check!

I snap up, forcibly untangling myself from my bed as my heart races and my cheeks burn a bright red. Again, I get up and do my ritual, hoping it will end the scenes of impending doom in my head, cool the rising heat in my body. It doesn’t.

Repeat this scene over and over—once or twice an hour—until it is five in the morning and my father is getting up to go to work. He takes one look at me standing in the hallway, my bedroom door open as I’m leaving to check the stove for what seems like the zillionth time.

“Go back to bed,” he tells me. I wish I could listen. Instead, I stand behind my half-closed door with the light off until he goes into the bathroom to shower. Then I slip out to perform my ritual again.

They tell me I can’t have it. “You don’t need that,” my mother will say. Her words travel to the temporal lobe, the part of the brain that recognizes the sounds, but it doesn’t matter. I hear that I don’t need it. The occipital lobe, the part of the brain that sees the item, clearly tells me it is junk. The frontal lobe, the part of the brain responsible for my rationality, doesn’t recognize why I need to keep it. But… I need it. The parietal lobe is trying its best to catch up, trying to tag-team with the rest to recognize why I feel so strongly that I should keep it. They tell me again, “Throw it away.” But I don’t. I can’t. The thought of not possessing the item makes me break out in a deep sweat; tears prickle. If I take it with me, they will take it from me. There’s only one way to keep it safe. I stick it in my mouth and swallow.

There is a box in the Janet Weis Children’s Hospital in Danville, Pennsylvania. Or there used to be. A small display case dedicated to me and only me. There’s no plaque, no card mounted on the wall next to it brandishing my name or explaining why it’s there. It’s really nothing more than a collection of small items, glued to a 12×12-inch piece of dark-blue velveteen inside a plastic case, secured to the wall behind the worn-out play set for younger kids. The only sign is a hastily hand-written message: THINGS SWALLOWED. There are six of these boxes, a collection from other children, but only one that has all of my things in them, from my youngest years of memory. The items are there for safekeeping, so no one throws them out. That’s what they told me, promised me, and that’s what I’ve come to expect. And I suppose it worked as a lesson to the other children: Don’t swallow these things.

They’re hard to notice, things you have to look for if you want to see them. But why would you? There’s nothing out of the ordinary in the boxes—especially in mine.

They’re all junk, things that should have been thrown away. Things that I couldn’t throw away. Things that I had to keep safe.

A soda tab that I bit in two. Two tacks. Twenty-six cents in change—two dimes, a nickel, and a penny. A 48-inch length of fishing wire. Four paperclips that I meant to use for a bracelet. A few rubber bands. A dog license in the shape of a bone. A plastic ring I got from a quarter machine. A pair of teddy bear charms found in my grandmother’s jewelry box. Usually things found in pairs, or even numbers. Two is an especially good number.

I stopped swallowing things eventually, finding the extraction almost as uncomfortable as the anxiety that came with it. I avoided bracelets and necklaces and rings and other trinkets, fearing that I would feel the need to put them in my mouth and swallow them. I tried to divert my attention by clenching my hands or biting my nails. I tried to focus, using the tips of my teeth to tear away small pieces of tissue on the edge of my lower lip. Anything to keep my mouth busy.

The urge to swallow things faded over time, but the compulsion to keep and collect never went away.

At age nine it was the milk cartons from the school cafeteria. The same milk cartons that I would precisely fold and compact into my Pocahontas backpack are long gone, thrown out in the middle of the night by my father. I would cry myself to sleep, curled up in the fetal position as my heart raced and images flashed in my head. The next day, I would start my collection over, even though I knew my father would yell and try to toss them again. At school, I kept my backpack in the corner of the cubby room, afraid that someone searching for their own similar bright yellow-and-pink bag might mistake theirs for mine and discover my hidden hoard. Then I’d have to give an explanation, even though I had none. So I hid it as best I could. I used a small bag shaped like Winnie the Pooh as my lunch box, and reached beneath the lunch table to slip the milk carton inside. When the class filed back into the room to put their things away, I would slide the folded cardboard into my backpack, where it would stay.

“Why do you keep these?” my mother asked one day, annoyed as the cartons spilled out of my backpack as I retrieved my homework folder.

I gasped, bending down to use my arms like a net to push them all back in. “I need to.”

“For what? What do you use them for?” She wanted to understand.

“I don’t use them. I need them.”

“For what?” she asked, her voice rising.

“I need them,” I repeated. It was the only answer I could give. I didn’t know why I needed those stupid milk cartons. It’s not like I took them out and looked at them, or arranged them in a collection. They just went into my backpack and stayed there. Knowing they were there made me feel better. Safer. Less jumpy.

Later in life I hoarded bigger items. They didn’t have any special holding place either, and have long since been thrown away, piece by piece, with every new Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor.

At thirteen, the object of my hoarding obsession was toilet paper. The two separate squares of toilet paper I used to tear off and stack neatly, one atop the other, in the cabinet above the toilet. Just in case.

In case of what? In case the world ran out of toilet paper. I would have a supply, just in case. In case I was having a massive nosebleed and needed tiny pieces of tissue paper to plug it up with. Sure, I could just rip it off the roll, but that might take too long. I would surely bleed out by then—at least that was the picture in my head. No matter how ridiculous, no matter how irrational, it made me feel better just knowing that my two squares of toilet paper were there behind the Band-Aids and my mother’s forgotten scrunchies.

Eventually my brother would find them, my separate stash of squares, while searching for another roll to clean up a mess in the sink. Eventually I would find my stack gone, and I would succumb to an anxiety attack—black out. Once revived, I would spend the next two days walking around with a nose plug on until I could repeat my bathroom ritual to restock my pile. Just in case.

Paranoia sets in, stress levels rise. Fight-or-flight mode commences, although flight is not an option and “fight” doesn’t seem to be the right word. Even the brain realizes the irrational switch, signaling the lungs to work harder. Oxygen will help, oxygen can calm it down. Wash your hands. Again. There are still germs. You’ll get sick, get an infection, die. Wash them! the voice inside my head screams. Serotonin is running near empty, making me agitated and anxious. All the time. Not to mention the constant, unshakable fear. The voice in my head has been repeating things for so long, I don’t even question it anymore. By sixteen, my brainstem surrenders to complete overdrive.

My mother called it PMS. My father called it “a phase.” My brother avoided me, afraid of the fits of anger or anxiety to which I had become susceptible. My friends described me as “quirky” and “passionate.” My doctor later told them: “Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.”

I was late to my doctor’s appointment – a routine checkup. I was physically in the office, but unable to respond when my name was called. When the receptionist came looking for me, I was standing at the sink in the bathroom. My hands were red, scrubbed raw by the half-bottle of floral scented soap and water turned hot as could be. One of my knuckles was bleeding, but that was nothing compared to the germs I was sure were all over my skin. They were crawling on me like ants, little microbes threatening my immune system. They were spreading from my hands. I swore I could see them, clustered together in a greenish hue swarm that inched its way up my arms as I scrubbed. So I scrubbed and scrubbed, sometimes using my nails to try to scratch away the germs.

Soap. Rinse. Soap. Rinse. Soap. Rinse.

Repeat.

It wasn’t the first time something like this had happened, but it was the first time it had happened in public—triggered because I had seen a woman sneeze into her hand and then use the same hand to turn the door handle to the doctor’s office, the same handle I had to put my own hand on to enter.

A nurse stood in the doorway to the bathroom, alerted by the receptionist. “She won’t stop,” the receptionist informed her, watching as I scrubbed and scrubbed and scrubbed. They didn’t try to stop me, to make me see that what I was doing was irrational and pointless, because they knew it wouldn’t work. I knew there were no green germs collecting on my hands. I knew I had already washed a hundred times. I knew this, but the green hue climbed up towards my elbows, and I could feel bile rising into my throat.

That wasn’t the first time I’d felt the compulsion to cleanse, but it was the worst. I had become accustomed to taking two showers a day, one in the morning and one at night. Every two days I would wash my hair twice. Shampoo: lather, rinse, repeat. Conditioner, lather, rinse, repeat. Shampoo: lather, rinse, repeat. Conditioner: lather, rinse.

Washing my hands was even more time-consuming. There are approximately 50,000 bacteria per square inch of the body, and even more on the hands. I was determined to scrub away all of them..

Nowadays doctors recommend singing “Happy Birthday” while washing. Twice. But my method was different. Standing at the bathroom sink, my hands soapy underneath the warm water, I performed a ritual I hadn’t noticed, something I picked up at camp.

Pete and Repeat are in a boat. Pete jumps out. Who was left? Repeat.

Pete and Repeat are in a boat. Pete jumps out. Who was left? Repeat.

Pete and Repeat are in a boat. Pete jumps out. Who was left? Repeat.

Pete and Repeat are in a boat. Pete jumps out. Who was left?

Sometimes two repetitions were enough. Other times, it took ten, twelve, fourteen times.

I was just being clean, I would tell myself. I could stop when I wanted, if I wanted, but I was having fun. Or, maybe not fun. But whatever the feeling was, it was a hell of a lot better than the stomach-souring feeling that came after using the bathroom and not saying it over and over. It was calming, even though my hands ached afterwards.

It’s a tradition that girls go to the bathroom in pairs, and I was no exception. I was usually the last one to leave, though, because my lavatory mate would finish washing her hands before I could. Teachers often scolded me for taking too long, lumping me in with those kids who took the bathroom pass and used it to roam the halls. In elementary school, the punishment was ten minutes off of recess. No big deal. I spent my recesses in the art room anyway. In middle school, it was dirty looks. So I started using the bathroom only between classes. That way, if I got stuck washing my hands, I could say I had been in the nurse’s office or had lost track of time talking to another teacher. In high school, I just stopped going to the bathroom during school hours.

When I got home from school, my mother would ask how my day had been. I would brush past her, ignoring the question as I raced to the bathroom. “Why don’t you go in school?” she asked me several times, annoyed.

“I don’t have time,” I told her. It wasn’t necessarily a lie. There were only three minutes between classes. “And they’re dirty.”

That was the short version. The bathrooms in my high school were the worst. Aside from the yellowing, chipped, and rusted sinks, the toilets were browning and didn’t flush. I couldn’t go in any of them without breaking into tears. The thought of having to go in there, use the bathroom, and then continually wash my hands in one of those disgusting sinks panicked me.

“Your kidneys are going to explode!” my mother told me. Why my kidneys were going to explode was beyond me. Truthfully, I never cared. Even if my kidneys exploded, it would be better than having to go into those bathrooms.

Dr. Maloney diagnosed me that day in the bathroom of his waiting room. After about an hour, I had finally stopped washing my hands. When it was over, he took me into his office, conference-called my parents, and told them I needed to make an appointment with a psychologist for a formal diagnosis. He made an appointment for me later that day with a colleague of his.

Dr. Akers, the psychologist, sat me and my parents down and explained. OCD manifests in different ways. He asked me what other rituals I performed when I felt jumpy and scared. He asked my parents what they had noticed that I hadn’t. By the end of the visit, I had been classified. Hoarder, washer, checker. That was me. For so long, these things had defined who I was, and now they had names.

He wrote me a prescription for some Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors —SSRIs. He told me they were antidepressants, which have proven useful in treating OCD. My mother asked him about other treatments, concerned that I would be on medication for the rest of my life. He told her, after hearing some of my peculiar, oddly funny stories, that I had been self-treating all along. Exposure Therapy, he called it. Forcing myself to stop swallowing things had forced me to adapt. My father throwing away my milk cartons had made me face my problems. The same with my brother using up my squares of toilet paper. Although it made me anxious, forcing more anxiety had actually helped me.

“Even with the pills,” Dr. Akers continued, “it will never go away. The obsessions and compulsions will always be there. You can’t get rid of it, but you can find ways to get around it.”

Iwas taught in high school that brain cells are kind of like trees working in reverse. The information starts in the cell body, the bulk of the treetop. A message is sent down the tree trunk to the roots. The roots get the message, and release it into the ground for another tree’s roots to absorb. Serotonin, the message, is sent down a tree inside my head. There’s not enough serotonin, not enough of the message to relay. The SSRI kicks in, adding more serotonin and strengthening the message. The message is able to move down the tree trunk, into the roots and into my brain.

“Franklin could count by twos and tie his shoes…” And that’s mostly why the Nickelodeon show about the boy turtle and his friends was my favorite as a kid. We had something special in common: we liked even numbers.

I had been attracted to even numbers for as long as I can remember. But it was never considered a significant part of my diagnosis until recently. Obsession with overt compulsions; that is what Dr. Akers calls it. My obsession is even numbers, but I didn’t have an outward ritual to diminish the anxiety odd numbers gave me.

This obsession doesn’t manifest itself in an outward ritual, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. When I see an odd number, I feel an internal compulsion to find a way to change it to an even number.

I’m nineteen years old, but 1 + 9 = 10.

I’m part of the Susquehanna University class of 2013, but 2+0+1+3= 6.

My birthday is a perfectly even number, 10 / 28 / 1990. Even when I add up the numbers, I’m still left with 30.

My first name has six letters. My middle name has four. My last name has eight.

Even my closest friends, the ones with whom I spend most of my time, tend to have names with an even number of letters. Alison. Samantha. Ally. Steven. Elijah. Mike. If a friend’s name has an odd number of letters, I assign numbers to the letters and continue my mental ritual until an even number is found.

S + A + R + A + H

is equivalent to

19 + 1 + 18 + 1 + 8 = 47

4 + 7 = 11

1 + 1 = 2

But some odd numbers can’t be avoided. I graduated from Dallas High School as part of the class of 2009. The big ’09 decorations from the stage had to be removed the day before graduation because I blacked out at practice, overtaken by a panic attack that my equations couldn’t soothe. Mr. Gilroy, my teacher and head of the graduation committee, saved me embarrassment by telling the rest of the students the decorations had been ruined when graduation was moved inside because of bad weather conditions. The silver ’09 charm on my tassel had to be removed because it kept swinging into my line of vision. As I crossed the stage, I cried because the diploma they handed me said “2009.”

“Susquehanna University” has 21 letters. 2 +1 does not equal an even number. It’s consoling to know that SU is two letters, but my heart still races a little faster each time I see the elongated name.

Crunching numbers provides relief. Paired with the effects of my SSRI, it makes my other physical compulsions seem less necessary. I still wash my hands at least twice, wash my hair twice, brush my teeth twice. I still hoard, but not as much. The things I do hoard are under my bed or in my closet at home—mostly empty boxes and bags, waiting for me to throw out when I finally recognize their uselessness. I still check the stove and make sure the door is locked before going to bed, and I still lose some sleep over it, but not nearly as much. The fears are still there—my family dying , my house exploding—but they are no longer as intense as they once were.

Counting has blanketed all the other feelings of anxiety and panic that come with my OCD, and even that could fade away as I continue to adapt. I’ll find a new obsession to focus on and a new compulsion to go along with it. Then I’ll adapt again. And again. Obsession, adaptation. Obsession, adaptation. Repeat.

About the Author

Nicole Lynn Redinski, Susquehanna University

Nicole Lynn Redinski is a junior majoring in creative writing with an editing and publishing minor. She resides in Shavertown, Pennsylvania. She has an odd fascination with elephants—so much so that some may even say she is obsessed.

About the Artist

Frances Lee, Oberlin College

Originally from Berkeley, California, Frances Lee ’13 is a studio art major at Oberlin, focused on drawing and painting.

No Comments