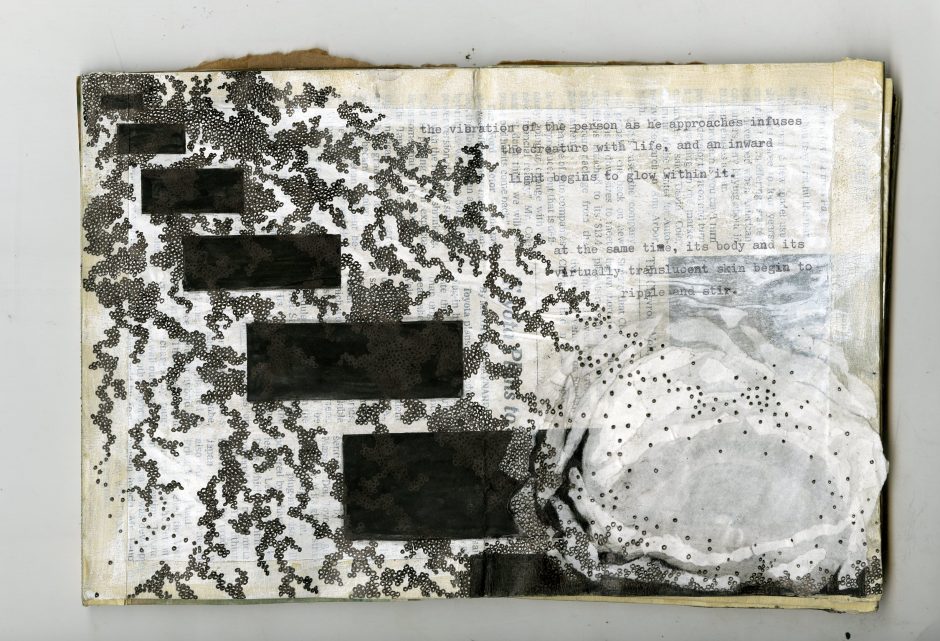

Excerpt from The A Bao A Qu, Zoë Goehring

[Trigger Warning: Depictions of Body Gore]DAUGHTER

It is morning. She remembers because when the day is bright, the linoleum tiles shine brightly in return.

That morning, she hears her mother cry out, and runs into the kitchen. Rice porridge is spreading slowly across the floor in a clotted, viscous mass. Dates, for sweetness, glisten in the pools of white rice. Her mother is sobbing and cursing her father. Sunlight brightly dapples cheap linoleum, cream-streaked-green in an imitation of marble. Fuck you, she says. Fuck your mother. Fuck your grandfather and your ancestors in their graves. The daughter runs into the bedroom, into the closet, to the farthest point away from the kitchen, burrowing deeply into the clothes. Soft wool and cotton brush against her face and muffle the noise outside.

FATHER

One day, I don’t know if it was in the afternoon or at night, you and Charlie were inside the living room. Wait, at that time there wasn’t Charlie. [Laughs.] Your ma was chopping vegetables on one side of the kitchen, boiling rice porridge on the other. She was using the pressure cooker, and she hadn’t closed the lid. Under normal circumstances, you don’t leave it open. I’m not sure how it works exactly, but she hadn’t been using the high-pressure function. If you use that function to boil ribs, you will boil the bones until they’re soft fragments, and you can crunch into them like peanuts. It’s that fast.

I went into the kitchen, trying to help. I didn’t know how to use the pressure cooker. I didn’t know, but I was trying to help. So I closed the lid. For these cookers, the pressure increases extraordinarily fast. She saw the lid shut tight and panicked. She opened it. The rice, boiling, spilled onto her hands, onto her entire right wrist. Her right arm. She ran her wrist under a little water, and when we saw her flesh fall off we both almost died of fright. I took her to the emergency room, where the nurses washed it and wrapped it. We went home.

Remember Alex? He was the boy your ma was babysitting. She wanted to tell his family she couldn’t babysit him anymore. Alex’s father still asked her to come. But she was scared, she didn’t want the scars to be too bad, and so she found a friend to watch Alex. You know that his father is a professor. Teaches cancer biology. His brother won the Nobel Prize in physics. I took your ma to his friend, a doctor. I had put medicinal paste on her wrist and wrapped it. The doctor took my wrapping apart, put on antibiotics, sulfa drugs.

Your ma is allergic to sulfa drugs. We realized this while we were on the road and her wrist began to swell. We went into a bathroom at a gas station and washed it away. We used toilet paper to wrap her wrist because we had no clean cloth with us.

When your ma was recovering, there were too many scars. Every time she looked at the scars she would say I did it on purpose. That I had wanted her to suffer. At the time, I don’t remember how you reacted. I think you were really scared and you cried. You were six. It was around Thanksgiving.

MOTHER

It was Thanksgiving morning. I was making rice porridge.

The kitchen was so small. We were so poor at that time, living in a space less than five hundred square meters. I was babysitting then. Didn’t have a job. Your clothes, my clothes, everything came from garage sales. Our furniture we found on streets. Mattresses, the sofa, pots and pans. Old pressure cookers.

Your ba has a problem. When I’m cooking—he’s never cooking—he stands around like a policeman on watch. He hops over here, leaps over there. If a pot is on the stove, he’ll peer into it. You’ll notice it next time you are home. If he didn’t do this, I would have been fine. It took so many years for it to become this color. It used to be so white, so ugly.

I was making porridge. The lid wasn’t closed and it wasn’t supposed to be closed. Your ba scuttled over and closed it. I opened it. The pot exploded and rice, all the hot grains of rice, got onto my wrist, my neck, my arm, my entire body. It felt like thousands of needles. The skin dropped off my right hand.

It was Thanksgiving and there were no doctors at the hospital. There was no medicine, the pharmacy was closed. The nurse put my hand in a basin with ice. I stayed there for many hours. The nurse cut off my cooked skin off with scissors.

Have you seen pig skin? Look at your hand. The skin looks paper-thin, but when it’s cooked and separated from your flesh, it looks like pig skin—that thick.

And you? You ran into the closet and wouldn’t come out. You hid and wouldn’t look at me, even when I came back from the hospital. I thought: this is my daughter, why would she be like this.

DAUGHTER

The father leads her to the room of pale teal where the mother sits, dipping her arm into a silver basin, a nurse sitting by her side. The mother’s face is swollen, eyes pushed into tiny slits. Look, she says. The daughter stares at the silver rim of the basin. Look at my arm, she says, louder. The nurse looks up. The daughter looks and pretends to see.

A week later, friends are gathered in the living room, loudly snapping and cracking sunflower seeds, spitting striped shells into napkins. The mother narrates the accident. And then it spilled all over me, she was saying, and you know what my daughter did? She ran into the closet and hid. She nudges her daughter, who has been gazing at the mouths of the adults, wondering how they extract seeds in one swift, effortless crack. Why don’t you show them?

The daughter hesitates, but when she feels a second nudge, she leaps up and runs across the living room, across the bedroom, until she arrives at the twin accordion doors of the closet. She slides them open.

Doors pulled shut, the air is warm and dark, and the clothes smell faintly of vinegar. Looking up, she sees them hanging like flattened cocoons, blurry black shapes, necks clustering the light that has leaked through the long vertical crack in the doors. They press gently against her face and her body, cradle her breath. Each slight movement is followed by a loud, silky rasp.

She hears muffled laughter, low and faraway, through the layered density of doors and fabric. Pushing aside their sinking weight—coiled necks collide, scraping a harsh clink-clink-clink—she emerges into the thin, yellow bedroom light. She runs back to the circle of adults, seeks out her mother’s face. Seeing a smile, she beams back, proud of the accuracy in her performance, her recreation of a monumental event. A glowing actress.

When the guests have left, the mother clicks the door softly shut, and looks at her daughter. Says, What if your father hadn’t been there? If I had been near death, you wouldn’t have known. I was in pain, and you ran from me.

I would give my life if it would save yours. You would have let all my skin burn, all my flesh drop.

Whenever the daughter sees the stippled white flesh of her mother’s wrist, she feels her stomach knot. She thinks she can detect disgust in the curve of her mother’s eyebrow when she tells her she loves her. For a long time, the mother does not make rice porridge, and the daughter stops eating raisins and prunes, miniature versions of dates.

About the Artist

Zoë Goehring, Carnegie Mellon University

Zoë Goehring of Carnegie Mellon University can be reached at [email protected].

No Comments