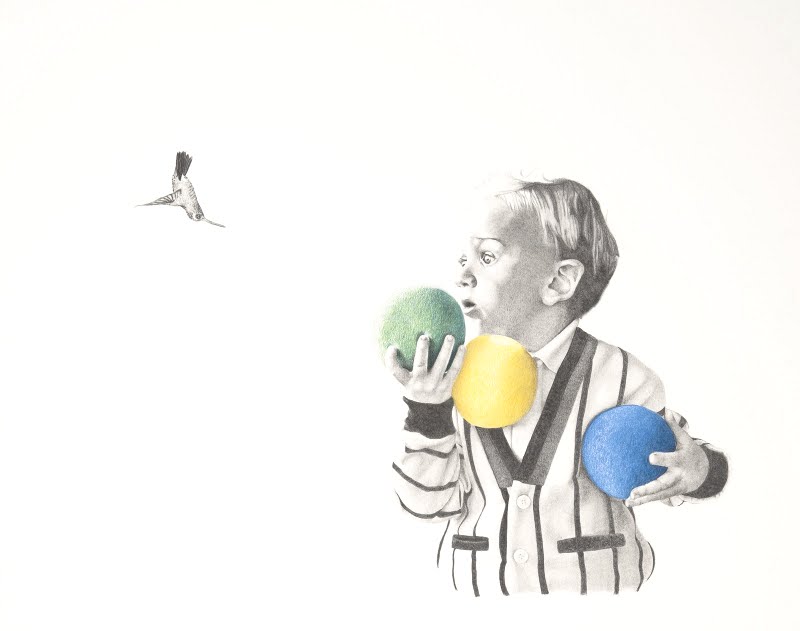

Nothing’s Gonna Happen Without Warning, Chris Winterbauer

Last night Fausto broke open a light bulb at home to see its innards. He held the precious thing by its screwy silver base, inspecting the wire and pieces, shards of hair-width milky blue glass at his feet as he squatted on the sidewalk outside his apartment building. His mother wondered at first why the living room lamp didn’t work.

Today Fausto’s class was beginning their electricity unit and would learn just how a simple flip of a plastic switch could turn on lights, could move currents across miles of wires, powering all sorts of incredible machines. Fausto liked to imagine bright strings of electricity circling the whole world every time he turned on a lamp or radio. He liked the feeling of connection.

Sitting alone at lunch as usual, his feet not quite reaching the streaky blue linoleum floor, his bony brown elbows splayed over the white table, Fausto worked his way through a peanut butter and jelly sandwich that, like all his peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, had gotten squished flat in his paper lunch bag. The jelly had squirted out and soaked through the white bread. He chewed and tipped his head back to glance at the fluorescent lights of the cafeteria, wondering where the electricity that powered them came from. How far away?

He finished his sandwich and pushed his glasses up his nose. Fausto carried a strap in his back pocket to keep his glasses on his thin face should he ever decide to play kickball at recess. This never happened, but he liked to be prepared. Fausto also secreted away his milk money in his right sneaker. This way, he figured, if he were turned upside down by bullies, his change could not possibly spill out onto the ground.

After finishing his lunch and throwing away his trash, Fausto turned his attention to his brown paper bag, the bag he’d used for lunch since they’d returned to school from the winter break. He withdrew a pencil from his pocket, playing with it awhile, shaking it between his thumb and index finger so it looked like rubber, something Bill Williams taught him last year in third grade. Then he spun it on the table like the spinner of a Twister board. He drew on his fingernails, then erased the swirls and cross-hatching, pulling the paper bag in front of him in order to continue his manifesto. Erasers on pencils should be bigger, he scribbled with a school-bus yellow #2. He wrote with his right hand, but was working on his left. He wanted to write with both hands, just in case something should happen to one of them, an accident: a broken wrist, an amputation, leprosy. Fausto liked the National Geographics and pictures in the medical journals at the library.

His handwriting was light and vague, letters crammed together as though there would never be enough space for everything. Fausto looked around the cafeteria, at the white, cinderblock walls, the high windows, the aides who stood around with walkie-talkies and frowns, the kids making each other laugh just to see if milk really could come out of your nose (it could).

Recess would be called soon, the aides herding everybody to the playground usually, but it was raining today—April didn’t bring May flowers, Fausto had observed, just more rain—so everyone would have to trudge back to their classrooms and draw, or play with those colored wooden pieces they’d use in math class sometimes. Fausto liked those pieces and always tried to claim them during indoor recess, but today he’d rather skip the half hour of free time and get on to the electricity lesson.

Straggling in the back of the line, Fausto was one of the last students to enter the classroom. Chris and Sal had a monopoly on the colored wooden pieces. Fausto bit his lip and went and sat at his desk, trying to block out the noise of his peers at play as he drew on scrap manila paper. For Fausto, the crayons in his desk had genders: red, yellow, and purple were obviously girls, and orange, green, and blue were their male, respective mates. Green always worried that Yellow would leave him for Orange because she was between the two of them. Yellow never left Green. Green worried that because he was a cool color that Yellow, a warm one, didn’t really belong with him. Wouldn’t Yellow and Orange’s warmth complement each other? Isn’t that what Fausto had learned in art class? But it didn’t matter; Yellow would always be faithful to Green. Fausto’s pencils, too, had lives, and he collected novelty erasers he never used. These erasers played roles in the pencil dramas. Sometimes, if he were bored during class—which he only sometimes was—he’d play with his pencils.

As aides came and signaled the end of recess, Fausto kept his pencils on hand because before the electricity lesson he had to get through Read Aloud. Every day, a student had to read from a book of stories their teacher, Miss Slokum, provided. Fausto did not like being read to. He liked his voice and his pace in his head; he couldn’t concentrate when someone else read the words. Instead of picturing the people and the places like he did when he read the words, his mind would wander, and he’d turn to the pencils for a more satisfying story.

Today, Janey Martinez was reading. Janey wasn’t bad. She had glasses, too, and liked the monkey bars, oo-ah-ing on them and pretending to eat bananas and groom her friends Allie and Marta. Fausto would laugh. But her voice was nasal on the best of days, and this week she had some kind of cold, rendering her words almost unintelligible. So the pencils discussed a heist of the vault (Fausto’s desk) as Janey Martinez stuttered and snuffled over a story of a farmer inspecting his fields of corn on a very hot day.

When Janey finished, Miss Slokum thanked her and asked her to take her seat. Fausto put his pencils and erasers away, reassuring them the heist would happen soon. Miss Slokum told them to get out their notebooks and pencils. Fausto already had his out, and started drawing curls in the margins like he’d seen in the broken light bulb last night.

Miss Slokum drew a light bulb on the board. It was lopsided, but she continued, drawing the curly wire inside of it. She drew a line from this wire and scrawled the word filament. Fausto copied this—once with his right hand and once with his left. The drawing with the left was pressed harder into the paper, and his light bulb was as lopsided as Miss Slokum’s, but he was improving.

The filament in a light bulb is made of tungsten,” Miss Slokum said in a clear voice. The word tungsten joined filament on the chalkboard. “And it conducts electricity.” Miss Slokum paused. “Now, who can tell me what electricity powers?” Fausto put his hand up, arm broomstick straight. “Yes, Fausto?”

“Refrigerators—”

“Very good, who else can—”

“Air conditioners, stoves, microwaves, TVs—”

“Thank you, Fausto,” Miss Slokum said, “but how about we give someone else a chance?” She scanned the room. “Michael, what else does electricity power?”

Fausto didn’t hear Michael’s response. He was too busy scolding himself. Sometimes he was too enthusiastic. He’d overheard his dad saying he didn’t like going to museums or into the city with him because Fausto would get too antsy, pointing at everything, mouth agape, asking too many questions. He wanted to touch everything, wanted to ask people on the street about the murals on the buildings or the people laying around vents with steam tendrilling up and out. Fausto had decided he wanted to live in Philadelphia near his dad when he got older. But he didn’t know what to say when adults asked what he wanted to be when he grew up. They’d prompt him: a firefighter? police officer? mail carrier? Fausto liked the last one the best out of all those ever suggested to him. He liked the idea of wearing a blue uniform and cap and carrying a big bag full of envelopes and packages, walking through the streets, greeting everyone, spreading news. He would give people letters and they would thank him. Maybe he’d get an award. Would he deliver his own mail? He smiled and hummed some marching tune he remembered from Fourth of July celebrations, something by someone named Sousa. He’d hum this song, he thought, when he delivered mail.

“Fausto.”

He looked up at his teacher, his eyes returning to focus on the now instead of an envisioned future. “Please stop humming, it’s disruptive.” Miss Slokum turned and picked up a tiny light bulb between the thumb and forefinger of her right hand and began to explain a simple activity that involved the little bulbs. “…so we’ll see how the current works to power the bulb. But before you pair off to begin—”

“What are they?” Fausto said, staring at the little bulb. “Light bulbs for elves?”

Miss Slokum sighed. Miss Slokum’s patience with everyone was wearing thin. The super of her apartment building had promised to fix the pipes under her kitchen sink over a week ago, but she was still washing dishes in her bathroom sink. “Fausto, please don’t waste our time. Go stand in the hall until I come to get you.”

Everyone looked at Fausto, faces blank. No one laughed because no one disliked Fausto. No one made apologetic faces at him because no one really liked him. So Fausto stood, breath coming short, and he walked in measured, even steps to the closed door. The knob was cool under his hand. He’d never had to go stand in the hall. Or sit on the wall during recess. He’d never been in any sort of trouble. Teachers told his mother that he was a bright, energetic student, that they appreciated that. But Fausto clicked the door shut behind him as quietly as possible. He stood, shoulders hunched, arms crossed, his pointy elbows sticking out. His glasses slid down his nose, but he didn’t bother to push them up. He tried listening to the rest of the lesson, to what the activity with the tiny bulbs was, but the door was metal and thick. He thought about peeking through the window, but he’d have to stand on his tiptoes, and Miss Slokum might see him. So he stood. Facing the water fountain. He wallowed in his situation by huffing loudly and pushing his eyebrows together over his nose and wrinkling his forehead.

“You standing in the hall, Fausto?” It was Joe, a chubby kid with yellow-blond hair. He carried a bathroom pass: a clipboard with curling papers and a stubby pencil attached with dirty white string.

“Yes.” He didn’t want Joe to be here, to know he, Fausto, had been sent to the hall.

“What for?”

“Nothing.” He stuck out his jaw and tilted his head downward, glaring at Joe.

“You musta done something.”

“Nothing. I didn’t do anything. Leave me alone.”

“OK. Fine.” Joe returned to his own classroom, a slice of chattering noise coming out of the door as he opened it. Mr. Beam’s class always had fun. And nobody got sent to the hall.

Twelve minutes later found Fausto sitting cross-legged on the floor outside of his classroom, head cradled between his fists. He stared at the flecked, white linoleum, trying to find faces or pictures. He tried writing on his paper bag, but no new thoughts joined his old sentences. One from September: Green always worries Yellow will leave him for Orange. Yellow would never do that, she’s too nice. A new day: Why is it called peanut butter? Another day, this one from October: But Green leaves Yellow for the city. Yellow cries. My sandwich isn’t cut. Today it’s one big flat square. Next to it are jellied fingerprints. Other sentences crowded the bag, observing the changing tastes of his cookies, and the several days when he bought chocolate milk instead of the Vitamin D fortified milk. He wouldn’t tell his mother. Doodles of everything: slices of cake, juice boxes, cubes, pyramids, covered wagons, stick figures waving hello.

He ended his examination of his paper bag and looked up and down the short hallway. He wondered what would happen if he just stood up and calmly walked out and back home. He knew the way, it wasn’t very far, and the only thing to be scared of were the two dogs that ran back and forth behind the chain link fence at the top of the hill, barking loudly, their cloudy, milky, blind eyes wide.

He’d just slipped his paper bag back into his pocket and pushed his glasses up his nose when the door cracked open next to him. Marta’s pale face framed with her blond stick-straight bangs and pigtail braids peeped out at him at his level.

“Miss Slokum says you can come back in,” she whispered, the gap between her front teeth flashing momentarily. Marta always smiled with her mouth closed.

Neither of them moved for a moment. Fausto glared at Marta even though he wasn’t angry at her; he’d just wanted to learn about electricity. Marta just blinked back at Fausto until he abruptly jumped to his feet and scuffed back into the classroom. Miss Slokum didn’t say anything as Fausto took his seat, she only instructed the class to take out their history books and turn to page 347.

They were learning about the pioneers. Families that packed all they could into covered wagons and trekked to Oregon or California across prairies and through all kinds of weather. They’d learned that deaths were high and accidents common. Last week they walked single-file to the computer lab to play Oregon Trail. Fausto got his family all the way to Fort Walla Walla, but they then quickly died of dysentery. Fausto looked up what dysentery was: infection of the intestines resulting in severe diarrhea with the presence of blood and mucus in the feces. He’d rather they’d gotten killed by Indians. At least Indians were exciting. Next week, on Friday, was Pioneer Day. Fausto had been looking forward to Pioneer Day since kindergarten when he saw the fourth-graders with their books bound with belts and their lunches in baskets. Fausto wondered if his mom could make lunch besides peanut butter and jelly, something more suited to a pioneer boy. Cornbread, maybe.

After dinner, still in the kitchen, Fausto’s mother, Yvonne, sat with her slippered feet propped up on another chair, her ritual after any of her shifts at the hospital. The small TV on the counter was tuned to some network show with people singing and dancing. Fausto watched her eyelids droop then pop back up. He wondered why she didn’t just go to sleep.

The phone rang, and his mother’s feet dropped to the floor.

“I’ll handle this,” Fausto said, trying to make his mother laugh. Instead, Yvonne propped her elbows on the kitchen table, rubbing her temples and reaching for the TV remote to lower the volume.

“Dad!” Fausto yelled when he heard the voice on the other end. “Dad, today in school we learned about light bulbs and last week we played Oregon Trail and my family almost got to Oregon but they died of dysentery and I didn’t know what dysentery was, so I looked it up and it’s gross. I don’t want to die that way and I wish my family hadn’t died of it, either. I wish Indians had gotten them. If they were going to die I wish Indians had gotten them, they’re more exciting than a bad case of diarrhea—that’s what dysentery is, isn’t that gross?—Indians have bows and arrows with feathers and the ones on the plains ate buffalo, lots of buffalo—” Yvonne gently unwrapped her son’s hands from the phone and brought it up to her ear.

“Hello, Gilbert. I hope you’re calling to tell me you’re going to send the money soon.” Yvonne cupped her thin free hand on Fausto’s head. He leaned into her side, his head just hitting above her hip. She squeezed his shoulder then released him and took her seat at the kitchen table. Fausto knew it was time for bed.

After he’d stripped down to his undershirt and pulled on sweatpants, he hopped into bed, under his quilt his grandmother had pulled from her attic. He took up his book from the library, How Things Work, and read into the night. He dreamed of pulleys and winches, levers and inclined planes, and flares of electricity looping around tungsten filaments inside bulbs of glass. He rode the filaments with the electricity; it felt like going down a steep, icy, slippery slide.

About the Artist

Chris Winterbauer, Stanford University

Chris Winterbauer is a junior at Stanford University majoring in English. He can be reached at [email protected].

No Comments