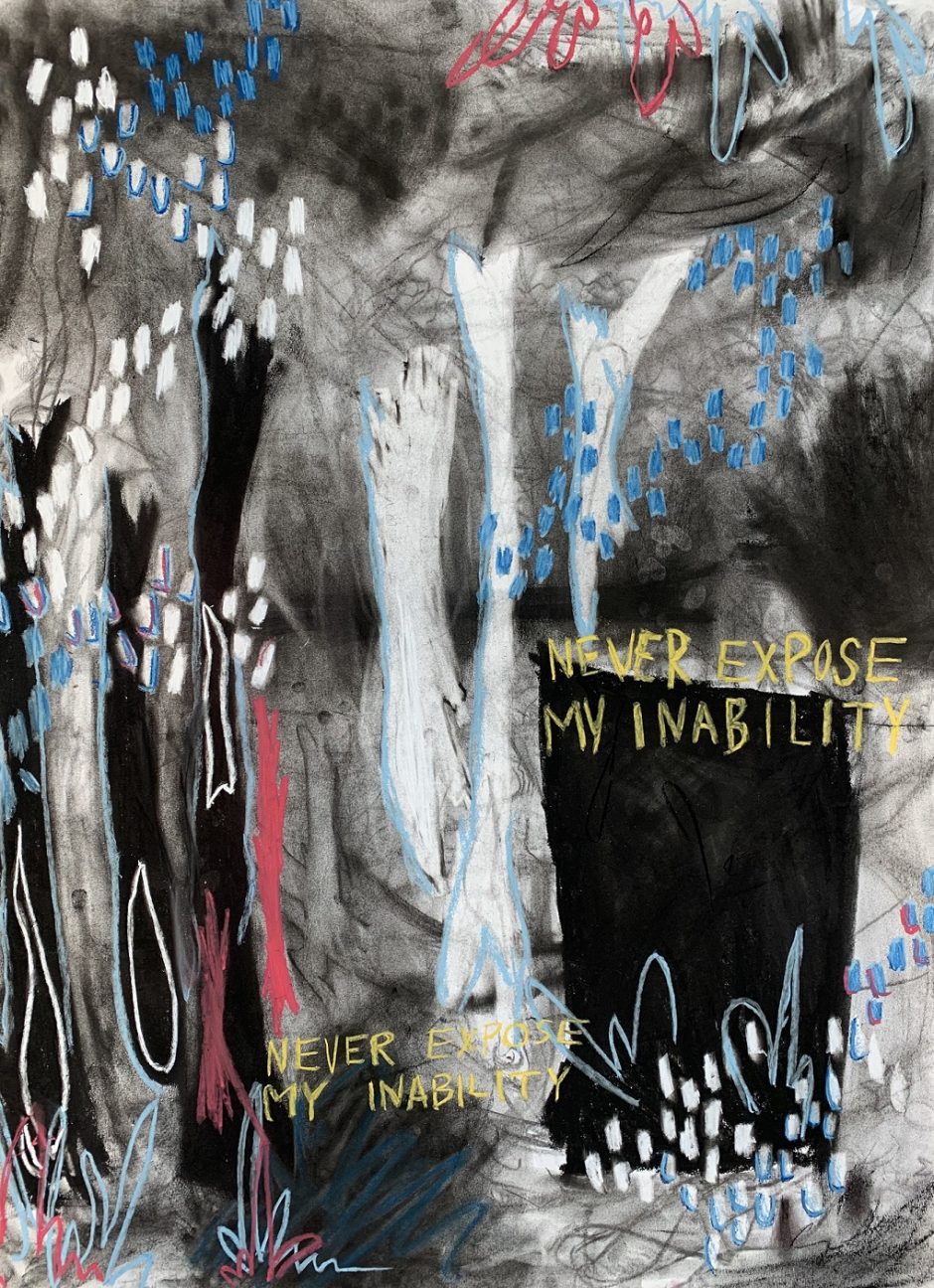

Whispers, Emily Bryn

Once upon a time, there was a great and beautiful giant named Pantagruel. He was cloaked in silver and fish scales. His robes were made of the skin of the river, and weaved in his hair was the starlight itself.

Pantagruel was not a happy creature. His heart moaned with a bitter ache of nameless source. Within him here or there, a stray finger must have poked through the fine muslin of his being. All joy that could be and would be was let out as a chilled smoke settling across the ground.

No earthly thing of metal or wire could plug the hole. No god shaped clay or cock shaped stone could sit with precision in that part of him where something must fit. But he was not without hope.

Across the world, beneath every familiar bridge and in all the alleys and sewers of all the great cities of wonder and history, The One Eyed Goon stalked and slogged through the beer vomit rain and cigarette smog. Though his flock of homebums and train kids were pious and pitiful, The One Eyed Goon was as fractured as the Giant. No amount of sniped cigarette butts from the pavement or pus-filled sores lining his lips could fit into the hole left in his head where the other eye, the eye that looks back ought to have been.

Out of all creeping things in the slimes and sludges of this world, only The One Eyed Goon knew how to cure Pantagruel’s cruel disease. They would build a living golem together from their momentous and shared grief and from clumping earth and twigs broken from the shabby trees dying by the highway. A perfect and simple thing as lovely and chirping as the cracked concrete and clodded dirt median whence it came.

They toiled and they labored. They broke knuckle and split nail. And with the acid rain that came from heaven and wet their creation, its heart beat and it was alive. The critters in the sparse grasses and the sliming slugs and rats and rodents running in and out of the moss and peat tickled its nerves and drank its sewage blood, driving it on alive, cruel and violent as a bitter winter. And in their work, now living and being and wailing into the weeping sky, Pantagruel and The Goon’s holes were filled with an echo of silence.

But as do all living things, the golem held within it a hole where desire should have been, seated deep and entrenched for good. The rain and the storms of summer leached into the golem’s dirty, rocky flesh, and the golem died of a sorrow that only a few real things would ever know.

As Pantagruel held the crying thing in his lap, the rivers and streams and the runoff and downpour tore apart the golem, carrying its dissected corpse into a nearby gutter. Soon the golem’s face and smile were all that was left, a few clods and pebbles in the giant’s slim palms. He clutched the golem’s sullen eyes to his chest and wept.

The One Eyed Goon would do no such thing. With no eye to look back, the Goon pushed on.

They would try again. They would use better ingredients.

They would use heartier parts made of steel and iron and oil. They would rob shipyards and burgle refineries. They would rip pipe from walls with their bare hands. No crane, no press, no machine within miles would be safe from their claws. Their new golem would be a monster of fire and sharp corners.

And so again they toiled. From a knot of pipes and cables and the engine of a school bus, a creature grew. The hands of the giant and the Goon were as stained with the oil of their new child as the mud of the old. And when the great mechanical automaton, a golem unlike any other, crackled and sparked alive, Pantagruel and The One Eyed Goon once again found themselves struck silent in the greatness they’d achieved. Gasoline and diesel pumped through its veins. Exhaust erupted from its lungs as it reared up out of the shipping harbor, spread open and roared.

But even things of metal and axle grease, things that live in flame and smoke, have a hole in them. A hole where some great nameless thing fits earnestly and elegantly. And so in a flash and a burst of sinister fire, the golem died of an anger that would burn the whole world to cinders.

In the light of the burning golem sinking into the harbor like the Colossus of a new Rhodes, the One Eyed Goon watched his greatest work burn and drown and decay into scrap. All Pantagruel could do was turn away into the shadows, taking solace in his starlight and his other beautiful trinkets. But The Goon knew what must be done. They would need real parts.

So they took up shovels and picks and held flashlights in their teeth and broke into cemeteries and snuck into morgues and tore and broke away and severed and ripped out every limb and every organ and every tangled nerve and hair they could carry in their weary arms and stole away into the night to do their fearful work.

Beneath a darkened moon, a moon too frightened to look at the horrors that would be done in its light, the One Eyed Goon and Pantagruel the Giant sewed these pilfered chunks of mismatched human viscera together with dental floss and stapled them with a rusty staple gun from a nearby construction site. They substituted engine parts for organs and piping for veins when their meatier supplies ran thin. They extended a leg with a block of wood nailed to a backwards foot and filled in the ribs with some broken pvc pipes and chickenwire.

Though their creation had all the makings of a living thing, within its chest, in a deep and hidden place where only a secret might be kept, a hole let in the air and the golem would not live.

Again and again, Pantagruel beat upon its chest to make its cast-iron heart beat. But there was only dead flesh and stalled out motors. He wailed in the dark and tore through his hole, ripping his gossamer-thin essence apart, letting all that was sick and diseased out to splash upon the ground. His starlights were washed away and his cloak of scales torn from his gnarled and cruel shoulders.

He took the One Eyed Goon around his neck, strangling the life from him, and with two monstrous fingers plucked the Goon’s last good eye, the one for looking forward, from its rotten socket and let the Goon die at his feet.

With the pilfered eyeball, he plugged the golem’s hole and at last, with agony, it lived.

The golem sat up and saw what the giant had done. The goon’s bleeding and deflating corpse was already beckoning flies and worms. The golem howled like some lost monster bound to myth and stood up tall over the giant.

Pantagruel, now only blistered skin hanging slack from tarred bones and nothing more, cowered from his creation. The golem took his head in its mighty hand and lifted him high above it. He cried and begged the creature to stay its rage and vengeance, but to no avail. With a horrible cracking of bones and ripping of nerves, the golem tore Pantagruel’s head from his body and dropped them both into the dust at its gruesome feet.

And all that was left of the great giant Pantagruel was a pile of putrid organs, grayed and dry skin, and what ooze was left now all carried slowly toward a ditch by a coming rain.

About the Author

Rebecca Petchenik · Portland Community College

Rebecca Petchenik is a queer writer, actor and organizer originally from North Carolina. She currently resides in Portland, Oregon. Her most recent play, KAIT, premiered in Portland as part of the Fertile Ground Festival in 2019. Her work has been featured in The Screen Door Review, the Pointed Circle, and across Portland Stages. She has a forthcoming collection of fiction and does regular short story readings in the PDX area. This piece first appeared in The Pointed Circle.

About the Artist

Emily Bryn · Saint Edward’s University

Emily Bryn is a Mexican-American artist in Austin, Texas. She is currently pursuing a bachelor’s degree in Studio Art with a minor in Gender Studies and Sexuality at St.Edward’s University. When she isn’t drawing or painting, Emily Bryn is creating apparel for her side project regarding immigration policies, where a percent of every purchase is donated to an organization aiming to help immigrants fight for their deserved rights. Emily has made apparel worn by singer Orville Peck, created an installation for Austin-based Korean restaurant Oseyo, is #1 in Visit Austin’s article of Artists to Look Out For, and has worked on designing a few state level political campaigns. See more of her work on Instagram @emsbrynart or her website, http://www.emsbrynart.com. This piece first appeared in Sorin Oak Review.

No Comments