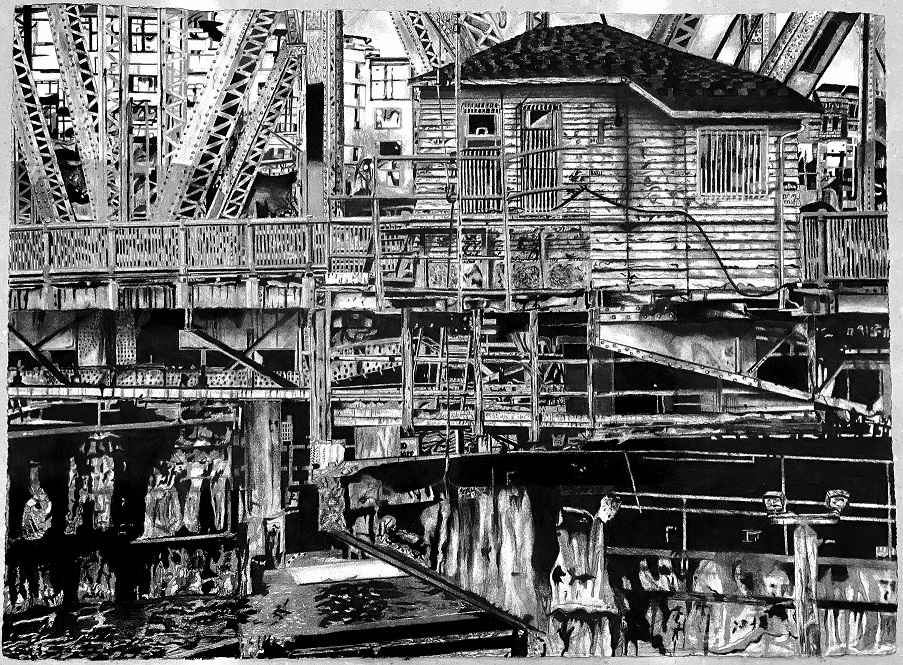

The Complexity of Detail, Olivia Offutt

I found the tense of life in my college French 102 class that I took because everyone I knew was in Spanish and French is the language of Voltaire, West Africa, and pretension.

“le sobjonctif” my Russian French teacher would say, is not a tense but a mood. Other romantic languages carry this mood iness, and even though the Indo-European language of my mother’s is proto-Celtic, my dreams resonated in the romantic.

Sitting in the back of my mom’s white Chrysler minivan, rum bling on the way to Long Island to visit my emotionally and physically distant grandparents, I would clutch my limegreen CD player and stare out the window at flashing oak trees and open limestone quarries, wishing I could talk to animals. My best friend would be a dashing thoroughbred named Thunder or Star who would be happy to give me rides to visit my array of other animal friends in the Mid-Atlantic region of Appala chia. Disney propaganda in the 1990’s led me to believe that megafauna was not only thriving in Pennsylvania, but that jaguars were actively seeking friendships with 9-year-old girls. That it was ok if you smelled and wore third hand clothes every day because it would probably increase your chances of a rich social life in the forest.

Le subjonctif is the tense of uncertainty and possibility, the “I’m not so certain, but…”

The I wish…

As I age from CD players to iPods, to refurbished smart phones, le subjonctif follows. Reminding me that if I was bet ter at French, I would be able to express fully the uncertainty, desires, and dreams that comprise the unlived reality.

But my somber Russian French teacher gave me a B-, and that’s probably because I cried during the final oral examina tion, choking out my sobbing conjugations that were hardly decipherable to begin with.

Now, the subjunctive moods that haunt my adult discourses are increasingly pragmatic, less fancy, but more fanciful for their radical diversions from reality.

Instead of befriending big cats, I wish I could remember to stand up for myself.

I have memories of being told that I am responsible for absti nence. Sitting in a wooden chair in a line of desks with other attentive forming frontal lobes, my health teacher flipping through gruesome photographs of inflamed genitals leaking unsightly fluids. Reminders to say no or face being a gross sexual pariah for life. But not how to say “no” in a way that could not be ignored.

I would remember that my worth is outside of my capacity to produce capital and forget the type of future talk that excludes the possibilities of dying a penniless writer.

I would wish that precarity was not a lifestyle choice that all my friends had to face. Be a full person or have a home. In stead, we eek out space for the subjunctive in a world that toes the infinitive, with its bland certainty, and the imperative with its patronizing directness.

You are penniless. You will die penniless.

There’s no room for conjugating into the unknown in this Proto-Germanic dialectic, which is the only language I can think in.

Je souhaiterais le vie libre.

About the Author

Kira Smith · Portland Community College

Kira Smith is a writer from Boalsburg, Pennsylvania currently living in Portland, Oregon. Her work focuses on the intersection of politics, space, and the environment. This piece was first published in The Pointed Circle.

About the Artist

Olivia Offutt · George Mason University

This piece first appeared in Volition. For more of Olivia Offutt’s art, visit her Instagram @oliviaoffuttillustration.

No Comments