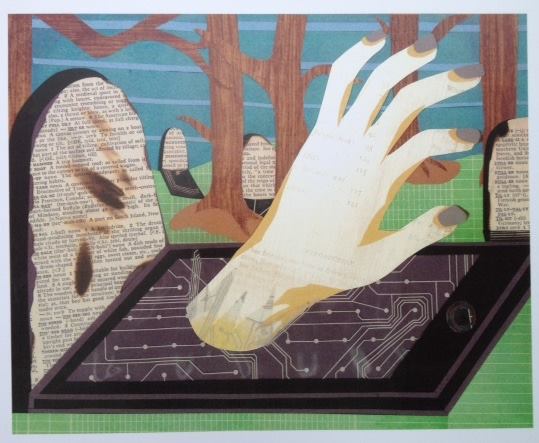

Talking Dead, Amanda Stephen

As a child, one of her favourite games had been holding her breath. This usually took place in the bathtub, still big enough to swallow her whole. She would let the warm water relax her, chasing the tension from her muscles and her lungs, before she went limp. Her back would slide down the tub until her little round face would slip beneath the water, soft brown hair turning gold as it floated around an even softer smile. Submerged, she would begin counting.

When she broke her old record, she would rise from the water triumphant and grinning, happiness and soap suds dripping off of her in kind. There was a satisfaction in fighting against her sense of preservation, staying under even when her body screamed to stop. The ultimate goal was, of course, to pass out, to wait until her body bobbed back to the surface when she would no doubt reawaken fresh from a few seconds of blissful unconsciousness.

Not that she had been able to test her theory. She never managed to win against her lungs. Childhood determination was weak against the burning that eventually ignited panic in her limbs, causing her to claw at the water’s surface until she rose up to meet it. Even so, she always tried again. Forced herself to stay under. She was not scared. The thought that she might stay submerged, facedown and drowning, never touched her mind.

Every year, death by asphyxiation appears in obituaries. Children choking on toys, suffocating inside plastic bags, breathing in toxic gases. The methods go on: Choking, helium inhalation, erotic asphyxiation. Blunt trauma to the trachea. Drug overdose.

Self-asphyxiation plagues a suicidal public. Ropes strangle the lives out of the hopeless, or, if the rope breaks, suicide feeds on food lodged in the throat even as the lungs starve. There’s little difference between choking on food and choking between your hands. You cannot find the death statistics for asphyxia; they are hidden inside categories like accidents, suicide, drowning, and choking. There are so many methods, but one outcome. Airflow is cut, carbon dioxide floods the system. Unconsciousness comes immediately; death comes soon after. These are facts she never knew.

And yet, something caused her to emulate the death records she would later read.

As the years passed, the game started leaving the confines of the bathtub. It crawled into bed with her, got tucked in under the same sheets. Instead of counting sheep, she counted how many seconds she could go without breathing. She hoped, if she just kept counting, that sleep would come quicker, a shortcut only possible for the brave. Instead adrenaline filled her lungs to replace the air she denied them, and rest became even further from her grasp.

She was too weak to control her own breathing, she thought, her will alone wasn’t strong enough. So she started smothering herself with pillows. Then, she began using her hands. She focused on making her palms meet, squashing her airway between them. The two hands never managed to touch. Her throat was always in the way, too full of air and too thick to strangle with thin fingers alone. No matter how hard she tried, just a bit of air would escape in and out.

Oxygen flow had never felt more like failure.

Walking down the quiet city streets, memories echoed in the darkness around and inside her. The words her therapist left with her were still spiraling in her head: “Juliana, you realize strangulation causes death, right?”

She had not known. It had seemed so simple when her therapist had said it, so obvious, but somehow she had never come to that conclusion. Shame painted her face as she remembered the childish ideas her younger self had imagined up, ideas she had never corrected even as her games turned into coping mechanisms.

But now she knew. She tried not to think about her neck pulsating between her shoulders, the hollow of it aching and loud. In the darkness, she pulled her scarf tighter.

Each hand held an end of the thin black material, tugging downward until she felt the two loops slide and encircle her neck like a constricting snake. The pressure was comforting, and as she drew it tighter it shrunk another size, a swallow just barely fitting down her throat. Another notch higher in the proverbial belt and a familiar burn began. She felt her throat close, the two walls of flesh touching, but with a shaking, shuddering panic she was aware of another shallow breath. Her eyes were zooming in and out of focus like a camera lens—the wind felt sharper and sounds grew louder on the street. She stumbled like a drunk, careening off the sidewalk before swooping back on—she wondered why no one could see what was happening. How no one noticed suicide walking with them on the sidewalk.

And as she was strangling the life out of herself she of course asks the question, the same question every mentally ill teen asks the neurotypical: “Why are you living?”

“Uhhhmmm” replied Katherine over the phone, her 16 year old voice drifting back to the other’s 16 year old ears. Katherine was her last hope. The last one who could save her from what she hoped to do to herself tonight.

“Like, I mean” she stammered to Katherine, trying not to let her voice shake, trying not to let the words reek of suicide, “why do you get up in the morning? Why do you chose life every day?”

Katherine was too young for these questions. Maybe Juliana knew that. They were both still in high school, but Katherine had faced a lot less death than her. She hadn’t had to wrestle these questions again and again. But that was exactly what she was looking for. She needed to understand how they lived. What kept them alive. What she was doing wrong.

“Uhhhm,” Katherine said again, clearly uncomfortable, “I don’t know.”

“You don’t know?” She sat up, but her heart felt like it had just sat down, steeled itself.

“I don’t really think about it.” There was a silence, and Katherine hopelessly stumbled after it. “I mean, uh, I live because I’m breathing, you know?”

At the time she hadn’t understood, couldn’t have understood. Part of her still didn’t. She had survived that night, but she was still looking for a reason. But while wringing her neck she asked herself again: what about breathing is so special? Why do so many people take it as a gift, and why was she constantly trying to return it? How can so many people cling to life while the only thing she clung to was her own throat?

And she realized in the moment that the world began to spin that she did not want to die. She had never wanted to die. She had wanted unconsciousness, yes, or escape, or a sense of control, but never death. And maybe, at least for now, that was reason enough.

The tips of her fingers still tingling with oxygen starvation, Juliana let go of the scarf. She felt the surface of the water rise up to meet her. She was ready to breathe again.

About the Artist

Amanda Stephen · Virginia Commonwealth University

No Comments