The Funnies, Justine Newman

My father drank orange juice with extra pulp. I never cared for the texture, but it was the closest we could afford to fresh squeezed. In those days, he owned an auto repair shop. He opened late every Friday—no one asked him why, or what he did with his free mornings. I knew he had been a “Peter Pan child”, so I assumed he would change into green tights when I left for school with my mother. Someone had told me that Operation Peter Pan was, “an exodus after the fall of Batista.” I couldn’t understand what that meant, so the idea stuck with me—he spent these mornings flying south to visit relatives I’d never met.

One Friday, when I was fourteen, I woke with a fever and convinced my mother to let me stay home. I slept maybe an hour more, a real break from routine. As I came down the stairs, I heard a Spanish voice beckon me from the record player. At first, I thought it was a fever dream. I couldn’t recall a time when my parents had used the wooden thing, kept under a pile of coffee table books. Near the bottom of the stairs, I saw a woman named Esther Borja on the LP cover. She stared back at me, lips held together in disapproval, like my grandmother during a conversation about politics.

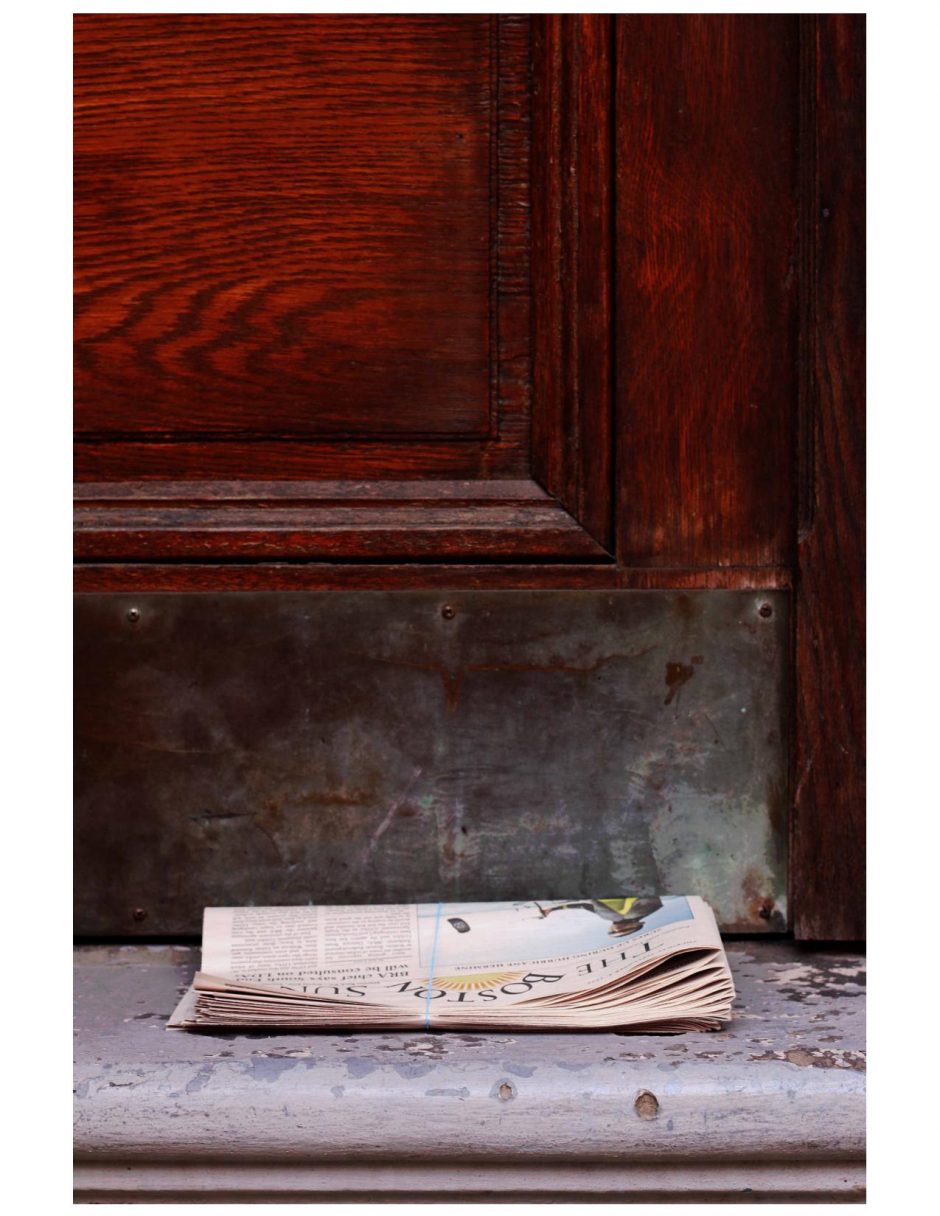

My parents never spoke to me in Spanish and only used it with each other during arguments. From that I deduced the curse words, and my abuela helped to fill in the rest. The tempo of “La Tarde” carried me into the kitchen, with its pale yellow paint and faux Tuscan backsplash. My father sat at the table, his back turned. I can still see his bald, tanned head as he read the newspaper under rising cigarette smoke. I approached him slowly, but made enough noise so that I knew he could hear me. When I sat down across from him, he didn’t lift his eyes from the paper. I studied the spread he had laid out for himself. There was a glass of orange juice directly in front of him. I could tell by its muted color that he had watered it down again, trying to make it last. Next to his coffee mug was a bottle of cheap bourbon, one whose hiding place I never found.

My mother forbade alcohol in the house, and I didn’t try to sneak it past her. In the late fifties she and my grandmother came to the States, leaving my grandfather in Cuba. Abuela wouldn’t tell me about him but I overheard her conversations with my mother. After I had been put to bed, they would sip tea in the kitchen and try to conjure the past. I would creep halfway down the stairs, just far enough to hear my grandmother say,

“Remember?” Over and over she described a man so loud, that even in sleep he woke the house with drunken snores. My mother denied her memories but whenever there was a neighborhood party, the smell of alcohol—in a drink or on someone’s breath—made her sick to her stomach.

I was surprised to see a plate of empanadas on the table because my father didn’t cook. We sat there for a few moments, him reading and me watching him. I pictured what he looked like as a boy. I no longer believed in Neverland, so I imagined him on that airplane, the first he’d ever been on. He would’ve had some trouble understanding the American stewardesses. Had he stared out the window as intently then as he stared at the newspaper in his hands now? What did he see in the clouds at 30,000 feet? Cubans feared the government would take away their parental authority—in a way they were right. Like most of the other children, my father never saw his parents again. The turn of a crinkled page finally broke the silence; I followed its example.

“Dad?” He still didn’t look up from the paper.

“I didn’t know you were home,” he said. He motioned to the empanadas. I chose one of the golden half-moons and took a bite, flakes of dough dropping onto the plastic tablecloth. It was still warm, the meat was perfectly seasoned—they were better than my abuela’s. He poured some of the bourbon into his mug, mixing it with his coffee.

“This is private,” he said, going to the fridge to grab me a glass of orange juice, one he didn’t water down. Was this a kindness on his part, an invitation?

When he returned to the table with my juice, he passed me the funnies. I’d lost interest in them years before, but it had been a part of our Sunday morning tradition growing up, and I wasn’t about to reject something familiar. As my eyes turned to Calvin and Hobbes, I realized I had crossed into a land I’d never been to before. One not exactly Cuban, nor American—separate from my mother, myself. It was an exile of his own accord. I took a sip of my juice and swallowed the pulp.

No Comments