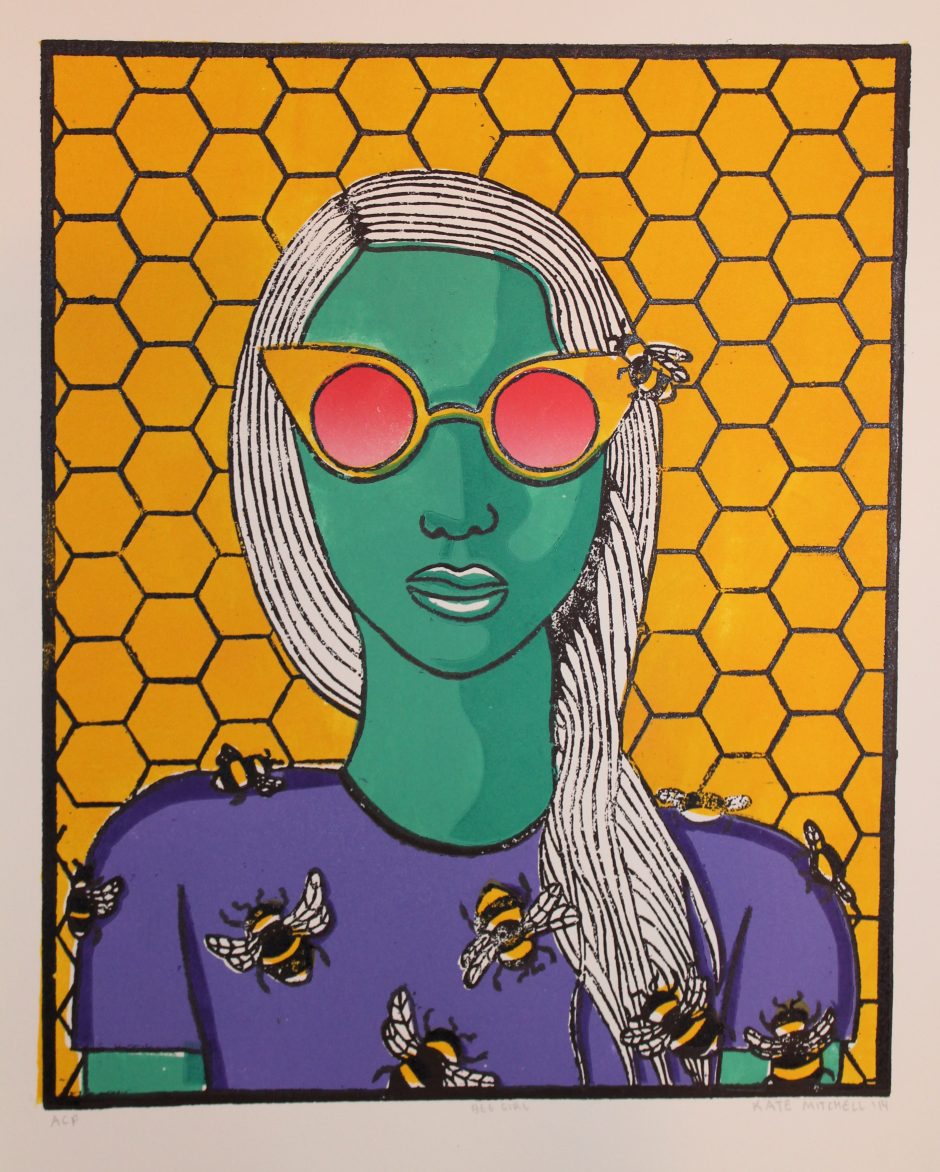

Bee Girl, Kate Mitchell

I am the woman bending on a busy sidewalk to scoop up the pests, the one pulling her car over on the 101 freeway to help one off of the windshield wiper and into some nearby bushes. I am the first to pry them from the shirts of panicked friends with my bare fingers while people share uneasy glances over my head.

It’s been twelve years since my obsession began, and my father and I still talk regularly of The Bee; of that beginning.

It was August in Southern California. This means that the air wasn’t moving, just buzzing drowsily in the heat. Shadows were small and rigid on the ground, only wavering in the places where heat rose from the cement as if called by a snake charmer. There were no clouds in the sky. No relief. Here, in August, eyes still squint behind sunglasses and sweat is an undefeated opponent. But I was ten years old and the heat could not suppress the scattered energy of a child. My father and I were on the driveway, leaving to go somewhere, I don’t remember where. A slow, small shadow moved across the pavement by my feet and my attention was consumed. I bent forward to investigate, using every hinge in my body to get closer.

We have all seen the struggling insect. The belly-up beetle, the fevered moth in the stick of a web, the housefly who can only buzz enough to toss itself half-heartedly at a window it does not see with any of its eyes. This was the dying bee, crawling slowly and aimlessly across the blistering pavement, moving his legs deliberately like an unpracticed toddler. He was fuzzy and more black than yellow. He was not like the smiling, blue-winged bees I colored on flowers and it felt strange, like seeing the moon in mid-afternoon, except this was a wrong I could right. Give any ten-year-old the opportunity for power and they will take it.

In the space between the neighbor’s driveway and our own, the underground access to each of our homes’ power lines was tangled in the unsupervised growth of golden poppies. My father and I had planted them because they require more effort to kill than they do to maintain, and I was ten, and even weed-like flowers are better looking than cement. A beige brick wall squatted around the poppies, only high enough to scrape shins on during games of tag and to cast unremitting shade on one half of the flower bed. Because of it the poppies were lopsided and unkempt, but they bloomed every year.

I snapped a leaf from a Lily of the Nile flower across the yard at its base, lean and long and canoe-shaped. I pushed the bee into the green canoe with my finger and sailed him through the air to the poppies. One last flight.

I did good. I chose the shady poppies, petals open to sun that would never warm them, so even if the bee had not died by morning he would not suffer death by roasting. I chose a cluster of corner flowers still sagging, somehow, under drops of sprinkler water and pushed him right to the center. I took pride in providing a comfortable death.

As I stood to admire my work, my father commending my good will over my shoulder, the bee began to buzz. He fidgeted violently. His defunct wings turned him in pulsing circles, and his legs writhed and pushed his body to the edge of a poppy petal that could not support him. His fall was broken halfway down by the web-work of a messy widow, who risked daylight for a juicy filet handed to her via petal platter and human god. She shot from her brick-fissure home as if propelled by gunpowder and latched onto the bee, turning him as one might turn 42, quickly and without much thought. Her limbs worked skillfully, artfully even, she was an experienced machine, until it was over and the struggle ceased. She finished her work and hung, suspended in her thread. Resting. I thought for a moment I should kill her.

But I didn’t have the guts to kill her for murdering my good intentions, and in the passing seconds I learned how much it hurt to be god. The widow turned and moved back through her web, satisfied, maneuvering around sticky clumps and debris back to her place in the brick. Food had come to her. She would survive, at least for the next few days. The bee would not.

He was so small in his sticky, grey cocoon, still and paused in the air making his transformation from honey-maker to meat. I was so big, casting my human shadow – but so small, trying to reconcile responsibility and fate, trying to learn if there was a difference.

I tossed the canoe-leaf into the bed of poppies. I felt the sun on the back of my neck, suddenly hot. The air was still and still droning with the sound of the earth reclaiming its carbon again and again and again, different bees and different widows. Busy turning canoe leaves into fertilizer for new golden caskets, opening petals to a sun that would never warm them. In a world that occupies such a pale speck of space, but occupies space, none of this matters – or all of it does.

We left to go somewhere, I don’t now remember where.

No Comments