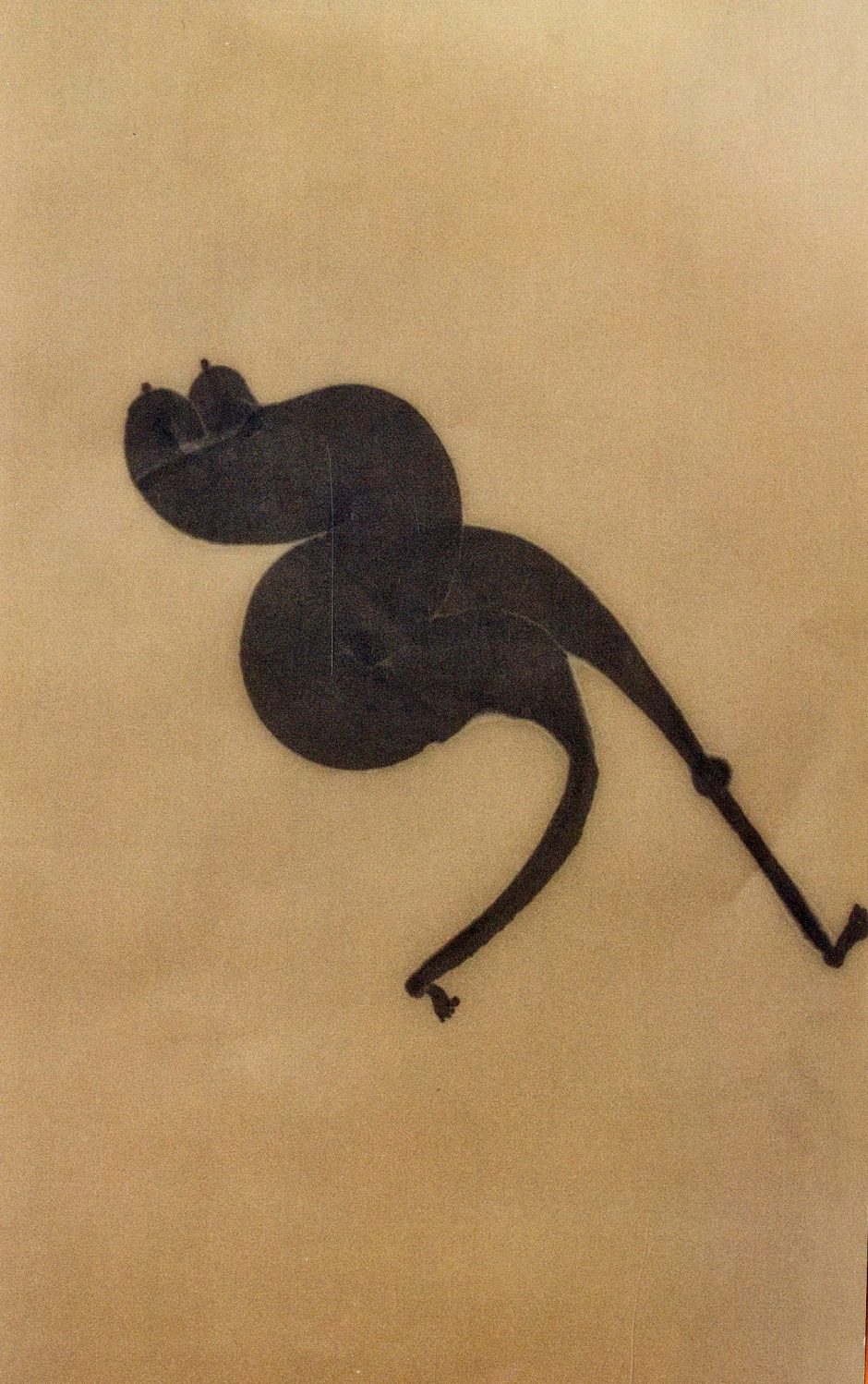

Cast Iron Gut, Grace Weaver

A fiction-critique of prose-poetry

She will skip stones across this still water where I once tried to drown the jealous burning in my belly and throw away my underwear that still smelled like God even after the red had dried almost black. She will skip stones across my unknown and then dip my head into the ripples that scare me. Then she will hold me there, combing my hair with fingers like love until my panicked gasps turn to laughter, clear laughter at the sky, when I realize I am not the only girl whose mother left her liverbroken. (You have read these stories before. So have I. For the same reasons we’ll read them again.) We measured how far away we were from the eyeglasses we forgot on our jeweled aunt’s dressing table by sniffing out dew drops of pastness and dustiness of new, because we’ve all had new before. Retracing where our toes stubbed on our way out the door, stumbling because our glasses were still on our aunt’s jeweled dressing table and the blur without them threw some clarity on my mother’s absence. Her absence splintered my stubbed toe and when my blurred eyes cried I fell into our jeweled aunt’s lap. And she cried dew drops of pastness with me until we had a pool big enough to sail away on, the two of us.

We talk about the insides of ourselves as dark. Perhaps it is because our eyes, merchants of information who deal in shape, distance, and color, do not work there. The senses we use in the world where we eat breakfast and take out the trash leave us blind when we go inside our memories and emotions. Platitudes frustrate us but we acquiesce, call the inside of ourselves “darkness,” “silence,” “unknowable,” and leave the mysteries to dig trenches between ourselves and our mothers. Jamaica Kincaid, in At the Bottom of the River, offers us a deal: if we agree to feel our way through her disorienting phantasmagoria of reptilian mothers, floorless houses, and blue-furred, androgynous, bee-eating desert creatures, she will make our dark, silent insides knowable. Along the way, she teaches us to perceive differently:

Taking her head into her large palms, she flattened it so that her eyes, which were by now ablaze, sat on top of her head and spun like two revolving balls. Then, making two lines on the soles of each foot, she divided her feet into crossroads. Silently, she had instructed me to follow her example, and now I too traveled along on my white underbelly, my tongue darting and flickering in the hot air. “Look,” said my mother.1

Kincaid’s prose-poetry defies the physical rules of tangible reality, the logical rules of cause-and-effect, and the psychological rules of emotional response. In the fiction we read comfortably in the daylight, authors give us a plot lived out by defined characters. They use images to help us find meaning in these other people’s plots. Kincaid gives us only the images to make what meanings we will. These images—disconnected, fragmented, distorted—are entirely her own, but our perception of them is entirely our own. As we begin to make sense of them, we begin to make sense of the memories and emotions too complicated for us to write into the stories we would if we thought we could. We find that if Kincaid’s giantess mothers, directionless boat trips, and shiny mud people2 resonate with us, they must resonate with others.

With that common resonance, Kincaid makes a space where the private is shared, where knowing someone else’s mind is an utterly intimate experience. In this shared space, we can feel how we need our uniqueness to save us from the nihilism and banality of being just like everyone else—and we need being like everyone else to save us from the loneliness and insanity of our uniqueness—

I was sitting on my mother’s bed trying to get a good look at myself. It was a large bed and it stood in the middle of a large, completely dark room. The room was completely dark because all the windows had been boarded up and all the crevices stuffed with black cloth. My mother lit some candles and the room burst into a pink-like, yellow-like glow. Looming over us, much larger than ourselves, were our shadows. We sat mesmerized because our shadows had made a place between themselves, as if they were making room for someone else. Nothing filled up the space between them, and the shadow of my mother sighed. They shadow of my mother danced around the room to a tune that my own shadow sang and then they stopped. All along, our shadows had grown thick and thin, long and short, had fallen at every angle, as if they were controlled by the light of day. Suddenly my mother got up and blew out the candles and our shadows vanished. I continued to sit on the bed, trying to get a good look at myself.3

Perhaps we do not have the courage to enter our most private selves unless we understand that it is possible to share what is hidden there with so many others. This is what we find at the end of Kincaid’s maze.

But first, we must let Kincaid lead us into a darkness devoid of plot and characterization. There is no sequence of events. The ‘I’ behind the stream of consciousness shifts constantly through space and time, never identifiable. The only structure Kincaid gives us is a series of surreal images strung together on threads of sensation and free association: fears become cows which lead to the sky, and as she contemplates the atmosphere, a noise interrupts and becomes a box stamped “Handle Carefully,” which reminds her of hospitals and having once passed a dead person.4Without plot or characters, we cannot tell from one image where the next will lead. We have no choice but to feel our way forward. We must touch everything—dust, slime, confusion of a mother’s slap, fury at a beloved brother—before our eyes can warn us away. Groping and stumbling, we find we fit more places than we expect to. We don’t have the comforts of sight, plot, and characterization to distance ourselves from this cool puddle of precocious independence or that cranny of rotten endearments.

If a sighted person goes blind, he must learn to measure distance with his finger span and practice how to identify objects by touch, literally strengthening a new part of his brain. Seeing with our fingers, familiar things feel strange and we mistake one for another. Kincaid shows us a mother becoming a lizard who tells her daughter to look with her tongue. She teaches us how to read a story when sensory perception fails to prepare us for what comes next. We have to trust her as she takes us in. We must agree to obey when she teaches us to look with our tongue.

When we learn a foreign language, we repeat new phrases as we encounter them, weighing the syllables and testing the angles of meaning. Kincaid repeats whole sentences verbatim and sequences of events with variations only in grammar. “What I have been doing lately: I was lying in bed and the doorbell rang. I ran downstairs. Quick. I opened the door. There was no one there,” and a page later, “What I have been doing lately: I was lying in bed on my back, my hands drawn up, my fingers interlaced lightly at the nape of my neck. Someone rang the doorbell. I went downstairs and opened the door but there was no one there,” and on the next page, “and I went back to lying in bed, just before the doorbell rang.”5 But the same words do not relate the same experience the second or third time around.

Kincaid’s odd images work on our minds like dissonant chords, and these repetitions work like phrases in music. When we first hear a pattern of notes that does not fit into the melodies we’ve heard before, we register only strangeness, and perhaps the ugliness we find in strangeness. Yet as the new musical motif repeats, perhaps with slight variation, it carves out a space to fit in our minds until it is beautiful, connects to other music we know, and builds an emotional response.

Kincaid teaches us this language of imagery so that we may open ourselves up, as if to new wavelengths in music, to the images that, after making us cringe or bruising us when we bump into them in the dark, give meaning to our more hidden experiences. If we take time to assimilate to her looping repetition and non sequitors, they align into our own plots of growing up, reluctant returns home, resenting expectations, rejecting love, or finding our independence. The more foreign the image, the more likely it fits into those secrets that are so uncomfortable we cannot share them out loud, or the secrets we might not have known ourselves until we brushed up against them in Kincaid’s labyrinth. We thought we’d want to forget them, but finding them on the page gives us an inkling that other people must have these ineffable memories and emotions, too. As our escort, she gives us the permission and the company we need to spend time with what we don ’t discuss because we won’t allow ourselves to think others could understand.

Dreams are a world of night illuminated. Kincaid’s transmorphing mothers, journeys that go in straight lines but bring us back to where we came from, and anchorless questions—all constantly shifting and cycling, folding back on themselves, resemble dreams. But dreams fade quickly as soon as we wake. By the time we glimpse something our dream might tell us, we are already beginning to forget it. We may approach Kincaid’s images as a dream—quite possibly all our own—on the page for us to read, study, and re-examine again and again until we learn their plots. Where is the plot in this maze of images? It is underneath our memory, in moments of feeling we had to put away for our own sake or for others’. Once we connect Kincaid’s foreign images with a plot that is entirely our own, we see our own secrets expressed in a book, a fictional space shared by an arbitrary collection of other readers, who must make their own plots from the same bizarre images. If we can share Kincaid’s images with others, perhaps the secrets that bridge our lives with her images are not so ineffable, not so unusual that we are alone in having them. Perhaps the nameless community of others might give us permission to share those secrets in the world outside of fiction, the world where we eat breakfast and take out the trash.

Kincaid’s maze takes us to a place where she has lit candles with her imagery, a place where some self of ours, other than the one holding the book in our hand, may commune with other selves, like the mother’s and daughter’s shadows. When her words on the page run out, we are left in the dark, still looking at ourselves. Our gaze is turned inwards, where we now know other shadows are dancing with us in the dark. We can arrive here because Kincaid’s uncomfortable images resonate with something of our own. In sharing that something, our minds find beauty in her distortion and in the moments we thought we wanted to forget.

In the end, Kincaid makes a pool where we can see ourselves reflected in all our uncried tears. A pool deep and clear enough that the rendings between mothers and daughters might drip through our fingers, beautiful for the moment we share them with every mother and daughter who has read this story and “watched each other carefully, always making sure to shower the other with words and deeds of love and affection.”6 She teaches us to see enough of our buried memories and secret thoughts to consent to their being fully part of us, making what used to be dark knowable.

The woman we call the river witch offers to take us inside as long as we give her our eyes at the pine-framed doorway. We give them to her to keep safely in the china cabinet next to the bookcase. How many hands can we hold in our own, after we blow out our candles and grin stupidly into the thickening black as she steps on the sparks with her sandy heels? We know it’s black because we breathe it cool and heavy in our throats. Whose hand is whose now is up to the stars and the way the pebbles fell in the dark. We dropped them as we stumbled in for to remember our ways home, but our pebble paths have only outlined an incestuous family tree upon the floor. The broken rules and confused mothers under our bandy heels are twisting our ankles to remind us that they are our only map back to the door, where we gave her our eyes, and we will learn what they have to teach us only if we ask them for directions in this river woman’s tongue of the imagined past realities that we buried because we were scared of them.

1. Kincaid, Jamaica. At the Bottom of the River. New York: Farrar, 1983, p. 55.

2. Ibid, p. 44

3. Ibid, pp. 54-55

4. Ibid, pp. 26-27

5. Ibid, pp. 40-45

6. Ibid, p. 54

No Comments