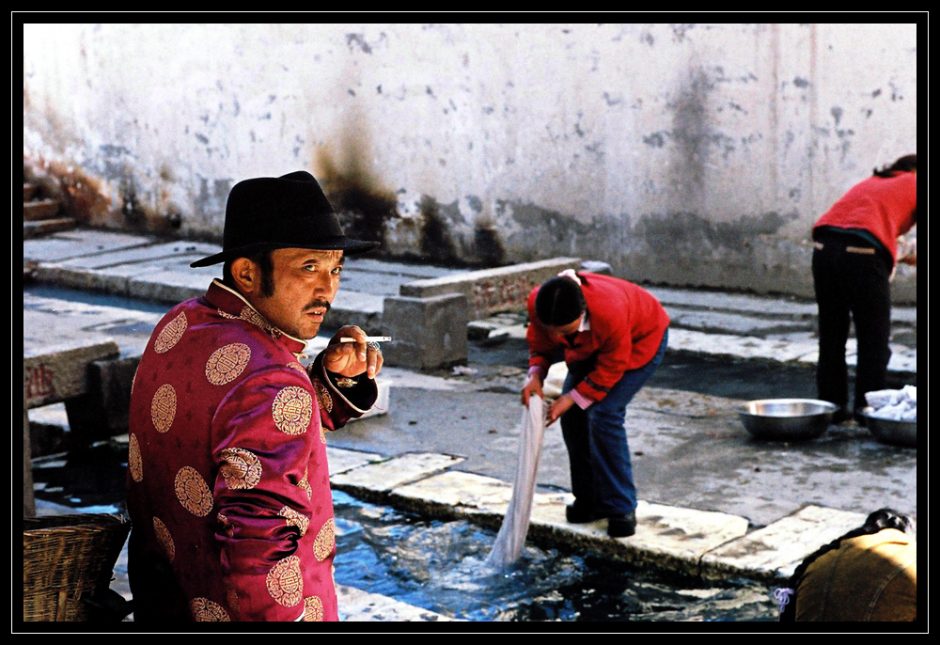

Kangding Cigarette Man, Jeremy Nelson

New Orleans: blues crackin’, hip swinging, finger-sucking, muckraking, turn the body into a song hot sweaty push you up against a wall humidity breathing onto you like a hot panting beast that can only be tamed by po’ boys and ice-cold daiquiris and crawdad crawfish sold by the pound get ‘em hot get ‘em raw get ‘em boiled but you better just get ‘em because when the sun goes down and the wind starts blowing and (if you’re lucky) the fiddle starts playing—you are going to want yourself some. Jazz band on a Sunday afternoon playing in the street, car stop just so the drivers can get out and dance, and holy lord! girls that have the bodies of fruit who make you want to cry they’re so ripe and the juices run down your chin and you thank god for sex and gumbo. Bayou, wetlands, swamp, trees that sway back and forth forever. Barges, boats, Mississippi River mud that holds the earth and holds the land and breaks it down and pushes it back up again and keeps the city breathing and beating to a heartbeat no one hears below the deep sounds of a spicy Cajun Creole masterpiece continuously churning towards tomorrow. Open windows, front porches, back alleys, three steps forward two steps back. Black vs. white, apartheid vs. not, hate so thick it crawls out of dark corners that never see sunlight and manages to plug up all the plumbing of the human soul. Parts of town that don’t see light skin, parts of town where the black man is silent when driving, parts of town where the rainbow colors flash and a man kisses another man outside in broad daylight. French Quarter, Louisiana sunshine, so many medallions of the fleur de lys it might drive a person crazy. And then there’s Bourbon Street, Bourbon Street, Bourbon Street! Mardi-Gras insanity dress up down to your toenails, beads of flashing bright enough to stop traffic, dancing with your hips and getting into all kinds of trouble with the catcalls, hand grenade drinks, the people working the salvation of their own personal god, and you swat yourself to the music on the street. Looks like this is the end of the line, looks like this is where god finally met the devil and decided to strike a deal, so alive you might die from it, you might hurt to look at it for too long, you might not be able to catch the beautiful breath of life in your lungs for one more precious second!

Musicians of wooden reed and blistered fingers and open guitar cases play on street corners and in dark bars. Everyone in the city understands: this here is music that makes you want to crawl out of your skin it feels so good. Fiddly playing, saxophone playing, drum and bass and harmonica and piano playing, just make sure something is playing because that’s what keeps us all alive, and if the music were to stop we would fall into something deeper than sorrow, stronger than anger, lonelier than being. You keep the music flowing, and New Orleans will be all right.

N’awlins. Say it like you want to fall asleep on the word, like you might faint with pleasure before you can choke it out. All the blues and reds of music and eating and dancing and sunning, the Big Easy and the bright future, dock town, saving grace, voodoo bayou, deepest denial, the city built on a swamp that care forgot, the racist, the southern, the lost, the frightened, the heavy, the slight, the baking and hot and humid and dropped, the fried and friendly: New Orleans.

In this swelling city steeped in a whole jambalaya of feelings, a disaster struck. Here is New Orleans at the end of a summer of witchcraft and strange weather: under twenty feet of inky black water. Hurricane Katrina swooped down with exact and cunning force, and the water rose. The Lower Ninth Ward and St. Bernard Parish were the hardest hit, and the levees of the Mississippi River broke. After a mandatory evacuation was issued, some hitch-hiked out or stayed camped on roofs or got transferred to the Superdome, the only building in New Orleans strong enough to withstand a hurricane. The tourists had caught the last flights or had driven away to safer lands at the first sign of trouble. New Orleans of sweet dream, sleepy rhythm; New Orleans: a skeleton picked clean.

The whole town, impossibly hurt. The whole world, unforgivably oblivious. Made into a rag doll puppet, strung out for all to see, calling SOS from the roof for someone to come save; five days passed without food or water, and shelters set up but no clean water to drink. No clean water! In the goddamn US of A. Home of the free and land of the brave.

America thought New Orleans was destroyed.

But the people came back.

They rode back on the insults of the whole country, telling them they were due for another big storm. Returning to the places that no one helped them leave, they began to pick up shards of glass, muddied flip-flops, to throw away the moldy couches and silent radios. They went to church and praised god with a genuine gratefulness, singing songs about the juiciness of being alive.

Slowly, the music waded back into the city. Pianists on Frenchmen Street played twice as long for half the tips. Seven boys set up their instruments on a French Quarter street, and people walking by gave them money in a hat and a cardboard box they’d laid out for offerings to the altar of hot-blooded music.

As the music played it began a slow hum crawling through New Orleans, creaking its way slowly towards redemption. It whispered into the hearts and minds of the people: Come along with me. We’ll make it, see here? Taste that saxophone, drink that clarinet, easy does it, rock-a-bye the blues, there it goes, it’s over.

New Orleans: shaky breath, mourning mother, boom box draw across the street, tap-dance delight, mid-afternoon mint julep. The city caring to forget, the city that forgot to care, the forgotten city of a thousand stories. A song creeps slowly, urgently back into itself. It unravels, reshapes, divides and multiplies. New Orleans brews hot in sweated out air. And the black and the white and the Cajun and the Creole and the everybody else keep movin’. The city dances electric on the waterway, thriving on the jerky violence that churns in the soles of its people, seeping out onto its scorching asphalt. The city dangles by one pinky finger on the windowsill of civilization, cautiously growing itself once more. The body of the South is voracious, begging for it to return to itself. What will happen now?

On one meager breath a saxophone starts playing late at night, someone hears the sound of a bird in the marshes. The rice cooker is brought out and a child gets mosquito bites in the twilight. The people know that it is good, or, at the very least, that it is going to be.

Rejuvenation is a gumbo, a fine and simmering soup that creeps into the minds and slips down the throats of those who came, those who left. Churning slowly, it is almost indiscernible from all other movement, weaving its way into the bodies of the people, plodding along towards the future on the damp and muddied shoulders of the Big Easy.

About the Artist

Jeremy Nelson, Reed College

Jeremy Nelson of Reed College can be reached at [email protected].

No Comments