Beauty and Power, Jini Park

If I had known it was Julie calling my name across the fluorescence of the supermarket, I wouldn’t have turned around.

“Maurine,” the voice called, again. I turned and saw her waddling towards me from the other end of the aisle. “God, it’s been ages!” she panted, catching me in her pale blue, sweaty embrace. I glanced down at her artificially red head, thinking about how old she looked. She was old. I was old. Except forty’s not old, I reminded myself.

When I pulled out of her arms Julie shot me this cardboard-looking smile. “What brings you in here? You’re not moving back to town, are you?” she asked.

“No, just visiting my parents.” They were old, too. Julie’s parents were dead.

“Oh how nice! How are they?” Her Midwestern drawl was unchanged. Exactly the same as when she used to say “Heya Mo, could I copy your notes?” as soon as I sat down. Physics was seventh period, junior year. We sat at the same lab table. Mr. Larson, the physics teacher, loved us both. We were undoubtedly his favorites.

I wonder, sometimes, if that’s why we lived.

“They’re fine,” I answered. I was having trouble, slipping in and out of time. We were in the cereal aisle, and the cartoons on the boxes seemed to be leering out at me.

“Hey Mo, are you okay?”

“Yeah, I’m fine,” I said. I wasn’t. The colors in the cardboard were running to the floor, mixing with the blood. It was still warm, as it seeped across the linoleum towards the rest of us, huddled in the corner of the classroom. “I’m fine.”

“You don’t look fine,” Julie said. Her voice was far away. How could she be standing there? Didn’t she remember? Didn’t she remember what had happened, why the rest of them couldn’t be standing here in a grocery store at forty years old? Somewhere, Clara laughed. Then I collapsed.

Clara. I hadn’t thought about her, outside of nightmares, in twenty years. She was a big girl with long lashes and shallow eyes. We were never close, but when we were small our mothers would have us play together. Clara, I remember, would always pull my hair. She wanted it, she said. She wanted my hair instead of hers. When Mr. Larson started shooting, Clara was the first to die.

Her fingernails were painted yellow that day. For the sunshine, she said. I remembered them because they were all I could bring myself to look at, after it happened.

And somewhere she was laughing; Clara was laughing. Laughing hysterically the way she had laughed when Mr. Larson walked into the classroom, shut the door, and pulled a gun from the black gym bag slung over his shoulder. Laughing in panic and disbelief. Julie and the supermarket were gone, now. I had fainted, I could feel it. I had fainted and come unstuck in time.

When I woke up I was much younger. Thirty-five. Kenneth, my fiancé, was sitting across from me. We were in the kitchen in my old apartment, at that reclaimed wood table I had rescued from an estate sale a year before. Kenneth was saying something. It was hard to hear.

“I just don’t feel like you’re invested in our future,” he was saying. What was he talking about? “In fact, sometimes I don’t feel like you’re invested in anything at all. In me at all. I mean, are you even listening to what I’m saying right now?”

“What?” I said. Wrong answer. His face began twitching with anger. It was so far away. “No, wait,” I said. “Of course I’m listening, of course I am.” A pang of guilt. He was a kind man, just bruised enough to be sweet.

Kenneth stopped and took a breath. “I know you’ve been through a lot,” he said. As he spoke I saw a paramedic with a birthmark on his cheek, the first person to meet my eyes after the police shot Larson. The first person who didn’t look away. Outside of the high school, sitting in the ambulance, he checked my pulse and looked into my face. His eyes were like lanterns, pale and distant through a poisonous mist. Kenneth’s voice was hazy. “But Mo, it’s so hard to always feel like you’re just—not there.”

What did he want from me? A mirror. A voice. A face other than my own. My mind wandered away from the table, away from him, into a blank, unassuming place.

“Dammit, Mo!” Kenneth was demanding, slapping his palms on the table. “If you’re not going to listen to me, I might as well go.”

Nothing was right. In my mind I was a specimen, forced into a jar and preserved in formaldehyde. Grotesque. Floating on a shelf, ready to be examined. I was a specimen, and nothing else; I would never emerge, readily-formed, the wife and mother and lover he wanted me to be. I was twisted, half-formed. Already dead.

Kenneth, sitting across from me. Wanting, demanding. It had to be done.

“Ok,” I said, inhaling, breathing in his anger and pain. “Go.” Kenneth stared at me with eyes like tiny explosions. Our imagined life, blowing up in his face. Shaking, he rose from the table and left the room. There was the muffled sound of the front door, slamming. Then I was alone. I lowered my aching head onto my crossed arms and went to sleep.

I woke up on the couch in my parent’s house, forty years old once again. Julie was there. She was sitting in an armchair chatting with my mother.

“Oh look who’s awake!” Julie said, turning towards me. I leaned out over the floor and threw up.

“Maurine!” my mother said. I just moaned. Julie ran into the kitchen and came back with a trashcan and a roll of paper towels. She and my mother hurriedly began to clean up before my effusion had time to damage the wooden floor.

“Looks like someone’s got a bit of a stomach bug!” Julie said. Her cheerfulness almost made me vomit again.

“Yes, indeed. But really, Maurine, you should have at least tried to get to the bathroom.” Age had yet to blunt my mother’s edge.

“Sorry,” I croaked. Even lying down, I felt unsteady. Like the world was a little wavier than usual.

“You poor thing!” Julie said. Then, turning to my mother. “We had just gotten to talking at the grocery store and then—boom! Your daughter collapses.”

“It makes sense,” my mother replied. “First time in years that she visits, of course she gets sick.”

My mind was lost at that point. Had it really been years? Yes, at least ten. The last time had been…Thanksgiving. When I was thirty. I began remembering it without going back. My body stayed forty, exhausted and heavy, pressing into the old solid sofa. What a terrible holiday. My mother had made a twenty-pound turkey for four people. Herself, my father, me and Kenneth, whom I had just begun dating seriously. Awful, the way she hacked at the bird, sawing into the cartilage of its leg joints, splitting the breast open to reveal pale, jagged, tender flesh. An image of my mother rose into my mind: the turkey supine beneath her smiling face, steam rising up out of its wounded skin and clinging to her glasses. And her mouth, moving, throwing out hints about marriage and children like they were cranberry sauce or green bean casserole. Kenneth eating them up, playing the game. Didn’t they know, even then, what that did to me?

Julie addressed me then, interrupting my thoughts. “You’re lucky Mo,” she was saying. “Forty years old and still so skinny.” I had no idea what she was talking about. Something about aging, gaining weight. “Nothing like me!” She laughed and patted her rounded stomach.

“Oh stop that,” my mother said. “There’s nothing wrong with filling out a bit. Perfectly natural. Especially when you’ve had children.”

“I always preferred my women with plenty of meat on them.” That was my father, shuffling down the stairs into the living room.

“No one asked you,” my mother snapped.

“She doesn’t mind. Do you, Julie?” My father was standing at the bottom of the stairs now, hands in his pockets.

“No, sir. I never mind a compliment,” Julie said with a laugh. I cleared my throat.

“Oh, look who’s awake,” my father said.

“She vomited all over the floor,” my mother offered.

“Not feeling well, eh?”

“Something like that,” I said. But my mind was going dark again, wandering away. My body was going along with it, this time. I could tell. Darkness, gauzy and demanding like sleep, began to creep over me. For some reason, I began to think of the paramedic again. Meeting his eyes, then sliding my gaze beyond him, to the untrimmed grass stirring at the edge of the high school’s parking lot. It was almost summer, and all of the margins were thick with growing things. Grass, waving. His birthmark, stretched dark and tight across his face. Julie, I remembered, had married that paramedic.

When time released me, I woke up at their wedding. My body was slim and nineteen in a dark blue dress. We were sitting, my parents and I, in one of the long wooden pews at the local Catholic Church. A contorted bronze Jesus was hanging on the cross, crucified above the couple and the priest and the clustering flowers. Daylight slanted through the stained glass, shattering across the back of Julie’s white satin dress. My mother thought it was beautiful. I thought it was sick.

“I, Julie Greene, take you, Ben Jacobson.” It was difficult to hear her, her voice came in snatches. “To be my lawful husband.” I had seen his eyes, poisoned with my own pain. His eyes, his birthmark. The grass. What had Julie seen? Something she could love, apparently. “In sickness and in health,” Julie way saying. What had she seen? Saving eyes. Caring eyes. “To love you and honor you.” She was crying as her vows came to a close, looking into the same eyes. What had they been, to her? Curious eyes? “All of the days of my life.”

“I now pronounce you man and wife,” said the priest. Rings were exchanged, they were marked beings now. Marked for each other; linked, set apart. When they kissed all I could see was Julie’s red hair, her white dress. Ben’s birthmark, lowered to her face. Slim bands of gold symbolized their connection, now. What did Julie and I have, I wondered, besides pain?

I hadn’t wanted to come to the wedding. My mother had forced me. “She invited you,” my mother had said. “You owe it to her, after what you two lived through.” So the slender bands of terror between us indebted me to her, apparently. But did it go the other way as well? Was there something, anything that she owed me?

People were standing now, clapping. The newlyweds were walking back down the aisle tangled in each other’s arms. In the back, where my family was sitting, people were crushing out of the door to usher them towards the curb.

Why had Julie invited me? I actively scorned her. Walking through the hallways, after the school had opened up again, I refused to meet her eyes. While she did interviews with Oprah Winfrey and NBC, I stayed in my room, watching and reviling her. But that wasn’t the reason I avoided her.

No. I avoided her because Julie’s face did something strange. It brought on…flashes, in my head. A disconnected bloom of blood, like a dance on the white-painted walls. Clara’s yellow-painted fingernails. The ear-splitting, gut-wrenching sound of Mr. Larson’s gun. Images fighting, crushing, rushing so fast that they began collapsing. Then my mind would go blank, lovely silence. The green whisper of waving grass. Soon I was taking different routes to class, using different halls. Staring at my shoes or at the wall if Julie happened to walk by. Anything to avoid that flashing pain.

Outside of the church, people were cheering, throwing rice as the couple walked towards the waiting limousine. How could she do it, I wondered? Bind her life to another’s, when both of those lives were so unstable and pained? Would they have children? How? I was only nineteen, but I already knew that was something I could never do. Not after what I had seen. Cans were tied to the rear bumper of the limo. They made a clatter on the pavement as Julie and her new husband pulled away. I stood in the crowd, listening to the metallic clangor. It could have been the dull ring of some great, broken machine for all I knew. Yes, a machine. The sound of it rose around me as the wedding, the crowd faded away. Something big, mechanical, was working furiously in the darkness which surrounded me. But where was it? Where was the sound? I was confused. Was it outside? Or was it in me?

Time was not working well. The clattering faded and I was sitting in my bedroom back at forty. Julie had left, mercifully, and I had managed to find my way up the stairs to the bedroom I had occupied when I still lived with my parents. The room had been redone long ago, but the walls were still the same pale green. It was the same furniture, too, cleared of the residue of a faraway childhood. Different sheets, no more posters or stuffed animals or cheap handmade jewelry. It was the same bed though, and the same ceiling I had stared at for so many nights, all through the end of high school, lying awake and hearing the echoes of distant gunfire. Seeing the faces, always the faces of those that had died. I used to repeat their names to myself like a prayer. Twenty-five names, everyone else in the classroom. Julie and I the only survivors.

That tortured me, that night. We had lived, but for what? For interviews like the ones Julie took, that exploited the deaths of twenty-five people for the sake of entertainment? It was a parade of the grotesque I always refused. Or was it for the fear I now lived in, of every backfire and enclosed space? Maybe it was so I could weep every time I heard that it had happened again, somewhere else. It never stopped. The numbers just grew and grew, like some ridiculous snowball of senseless violence. And so many lives were crushed, lives like Clara and Kyle and Josie and Brian. Lives like Julie and myself.

But still, I was lucky to be alive. My body, sick and exhausted, pulled me back into sleep. Back into the past.

Eighteen. The summer of my senior year. I was sitting outside of the school, watching the edge of the parking lot. The grass had begun to grow again; it had been almost a year. Julie sat down beside me, although I didn’t immediately realize she was there. The presence I felt beside me was too quiet to be Julie, I thought. Too sad. It didn’t occur to me to turn my head and look.

After several minutes Julie spoke. “I can’t believe it,” she said, voicing my thoughts. “Only a few weeks, and then it will have been a year.” Her voice was thick and hollow, like the bones of a bird too heavy for flight. When I heard it, I began to sweat. I said nothing back.

“I have nightmares, you know,” Julie said, ignoring my silence. “About being trapped in rooms without doors. About pulling the trigger myself.” I could smell the petrichor of her tears gathering. But I knew they would never come. Not in front of me. “And you know what it’s like, the way everyone knows what you’ve been thorough. Looking at you like you’re some sort of explosive freak.” A gentle wind sent a ripple through the sprouting grass. I strained my eyes to see. Even though I knew Julie was expecting an answer, I stayed just as silent as before.

“Why won’t you talk to me!” Julie cried. “You’re the only one who knows and you won’t talk to me!” Her voice rose at the end of her sentence, dangerous and strained. Then there was a long pause in which I tried not to listen to her breathing.

“I heard you got into Harvard,” Julie finally said. “Congratulations. Did you write your essay about the shooting? Is that why they accepted you?”

“Yes,” I said, licking my lips. “Probably.” Neither of us spoke again. Julie sat beside me for several minutes and then left as quietly as she came.

Darkness; time slipping again. Fluorescent light pouring from the distant ceiling. I was back in the supermarket. Julie was smiling at me. It was viscous. What was happening? Hadn’t I fainted?

“What’s the matter, Mo?” she said. “Still won’t talk to me?”

“You didn’t notice?” I asked. I had been gone so long. She had asked if I was okay, hadn’t she?

“Didn’t notice what?” For some reason it was easier to hear her voice than anyone else’s. “Hey, did you ever get that picture I sent you? Of Garrison?”

It took a moment for me to remember what she was talking about. A few months ago, there had been a letter from Julie with a newspaper clipping inside. An article about her oldest son.

“The boy who won the science fair. Yes,” I said, nodding. There had been a black-and-white photo above the text. A lanky teenager smiling in front of his winning project.

“You never replied. But still, I had to send it to you.” Julie was standing between me and the end of the aisle, blocking my escape.

“Why?”

“You know why. Because it was taken in Larson’s room.”

“Yes. I recognized it.” It was difficult to stay anchored in this dull, terrifying place filled with food and unknown people. My mind reached out to Julie’s hair, twining itself in the redness to brace itself against the churning rush of time.

“They had the winning projects set up in there. Knew what they were doing, too. They wanted me in the picture with Garrison, you know. Said it would make a great bookend-type story for the paper. ‘Mother’s trauma, Son’s triumph.’ That’s what those bastards wanted the headline to be.” I nodded. For the first time in my life I wanted to grab Julie, beg her to hold me so that I wouldn’t be swept anywhere else. “I said no, of course,” she continued. “But I sent you that picture because, I don’t know, I just wanted you to get a taste of what it’s like living here, in the same place. Sending your kids to the same school.” I didn’t realize how long I was standing there scrambling for words, but after about a minute Julie said, “As talkative as ever, I see.”

“I’m sorry.”

Julie shrugged. “It’s okay.” Okay? Had she understood? “But I guess that doesn’t mean that much. It all could have happened yesterday, you know? Or not even yesterday. One minute ago, one second.” We met each other’s eyes. For the first time in years, time stood completely still.

Then it was gone. My mind was pulled out into the crushing flow, spinning. Grass and blood and eyes and fingernails. Pretty yellow fingernails but there was the blood on them again. A birthmark. Bodies, rows and rows of bodies, twisted and small, shut up in jars, suspended on shelves. I was walking through them, transfixed by the comforting, alien beauty. A broken hand. An open, swollen eye. Tails and fins and formless flesh. Fleshless form. All serene, all knowing as I walked through the rows, searching. And there, that space on the top shelf. A missing jar. That was for me, waiting. Calling. And my heart ached. Oh! My heart ached. It burst apart because I could not reach that empty place throbbing like a gap tooth on the top shelf. All of me was pulled towards it. I felt as if it had the lightless density of a collapsed sun. But that was not enough, not enough. I could not get there by myself, I knew. Not by myself. I began to cry, because it was then I knew I would have to wait.

“Maurine?” Julie was saying, reaching out to me. “Jesus Mo, you look like you’re about to faint.” I tried to shake my head no, I’m okay, don’t touch me. But the darkness was creeping in. “Just take a breath,” Julie was saying. “I know it’s hard to remember all of those things.” But time was pulling, dark and thick like viscous wind. Fading, all of it was fading. Julie’s voice was the last thing I heard.

“Come on Mo,” she said. “Let’s get you home.”

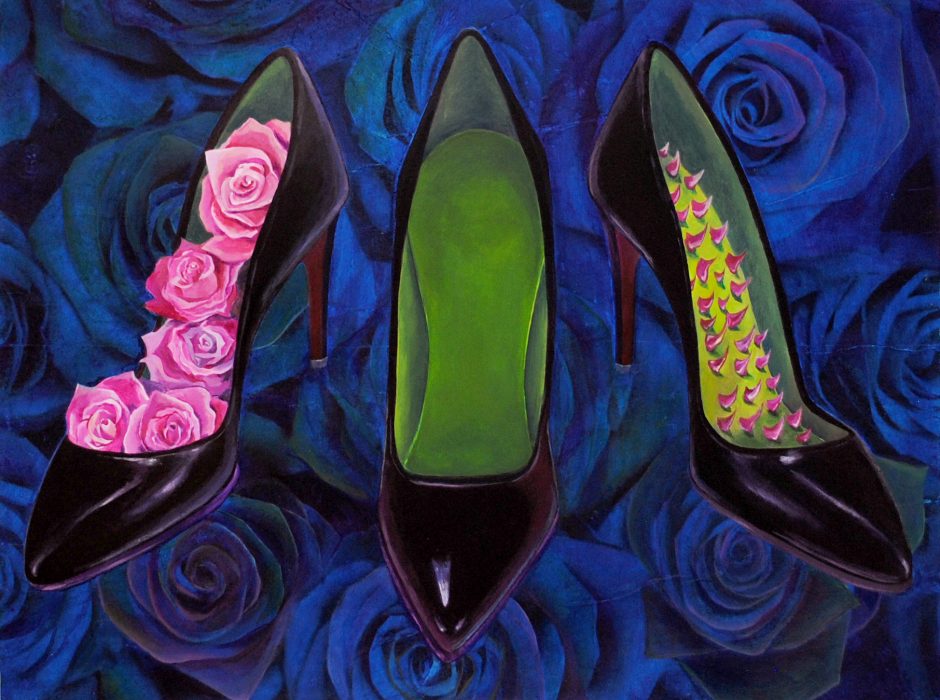

About the Artist

Jini Park · Virginia Commonwealth University

Jini Park is a sophomore in the Painting & Printmaking department at VCU. She hopes to continue to be the artist that creates works that will help people stay connected and motivate them be more aware of one another; to take a step toward a more affable society. This piece first appeared in Amendment.

No Comments