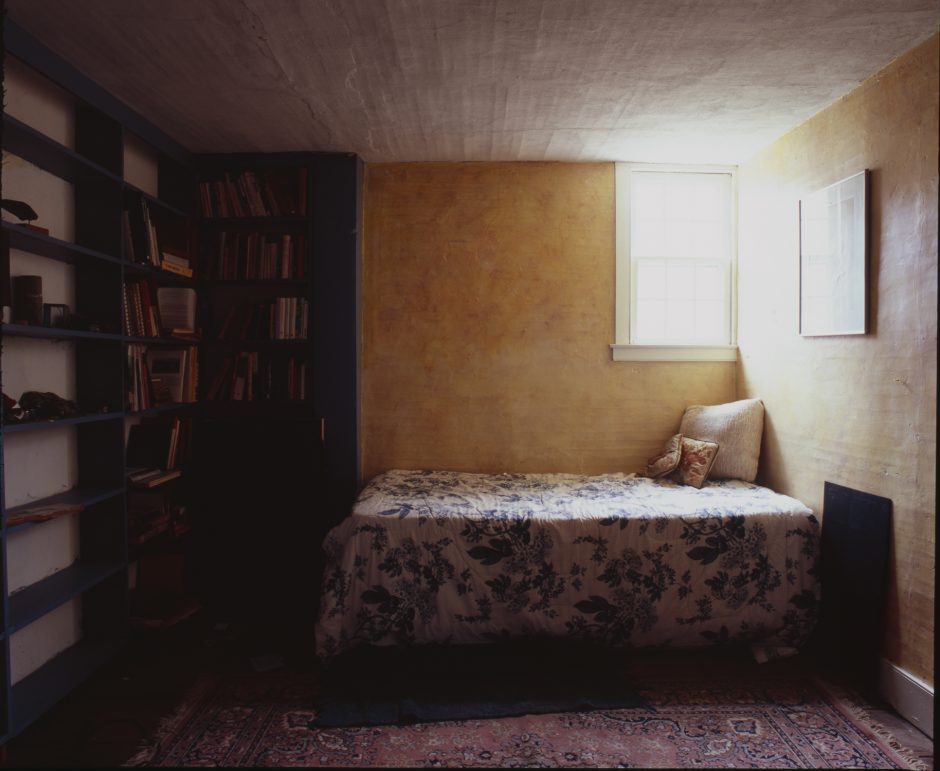

Library, Brittany Whiteman

[Trigger Warning: Graphic Depictions of Sexual Assault]In the night, there will be a sound like a beating heart and it will be your own. In the bunk below yours, the girls are up to the usual shit. Tracy has stolen a bracelet from Ms. Jenkins who does rounds and is trying to sell it for fifteen dollars. Later, Tracy discovers that the head of her Justin Timberlake poster has been torn off, and you rub it in your palm under your pillow. She shhhhs the other girls and gets up to see if you are awake. Stare into her ugly, fat face. The state-issued window bars make patterns like geometry on her skin, and orange steam rises outside from the heater in the basement as if from a kind of hell. Pretend not to be scared of her.

“Hey, Hope,” she says, and puffs up her fat cheeks, and then punches you one, hard, right between the legs.

After a time, realize the sound is coming from down there, a dull ringing you can almost hum. Touch yourself there and the skin feels numb and thick and dead. Later, when you get up to pee, terrified that Tracy will grab your ankles as you climb down the ladder, you will find a used tampon in your shoe. A weapon.

Wear short shorts to school, jean cutoffs that show off your thighs. On the long bus ride to the public high school, goose bumps appear there suddenly like a secret you tried to hide. Sit with your legs spread apart during algebra and biology. In history, Jason who sits two rows behind will give you the eye, staring at your breasts, your legs. You know how it will go. He will pass you a note: “Check one: 1. chem lab, 2. parking lot behind building C.” There will be square boxes. Some things get easier, others harder; which is which? You have next period free anyway.

After Jason is done, he will take your hand, and ask you if want to do it again. Toss your frizzy blond bangs out of your eyes and consider. His hands are soft and hot and clammy on your neck and you cannot see for a moment through the pins and needles and those hands do not belong to Jason any longer, but to him, that other boy, afternoons after school when your foster mom wasn’t home. He would corner you by the plastic kitchen table where he would take your arm and press into you saying, “please,” asking so politely, you almost felt in charge. Or he would take you outside, down to the secret waterfall, heaving and wheezing into you, then offering you his hand, so clammy and hot, up out of the pile of leaves.Leading you back towards the house, he would warn in a high, whiny voice, “Don’t step on the red ones! They’re poisonous. Don’t step on them or you’ll die,” pulling you faster and faster.

Once, you made up your mind to tell her. Your foster mom was watching the morning soaps.

“Pat,” you said, finally, after minutes of working up your courage.

“Shhh,” she holds a finger to her lips like a cross, “Don’t wake your brother. You know what the doctor said.”

Get caught the second time by Mr. Howard, coming to clean the lab. The school principal has a new secretary, a thin stupid woman who wears suits that are too big for her. Feel superior as you wait, and swing your feet like a child, savoring the loud thuds they make against the linoleum wall. Jason is there too, looking bored, and playing with his cell. Look at him and decide he is very good looking, that you could’ve done worse really, that he is really pretty hot and not all that pushy and what was the big fucking deal anyway?

The secretary smiles at you gently, from behind her beige metal desk, as if you might be easily broken. She will imagine, and she will pity, and her pity stinks, a smell like something dying. She puts her hair up in a ponytail, making sure no strands are left astray. You are almost touched. Decide she is definitely a virgin.

The principal opens his door. “Hope, we’re ready for you.” Who’s we? you think as you get up, and saunter through the doorway. Focus on the terrible job he is doing of combing his hair over, the strands clumped and oily as paint. See Mr. Howard in the corner in a corduroy suit the color of mustard.

Suddenly you feel tired, so very tired from a place that is hard to locate, like the core of you, the back of your back, but bigger, deeper. Your body is exhausted, can’t sleep at night, terrified that Tracy will get her hands on the few good things you still have: a silver crown for being second runner up in a beauty pageant, a tube of cherry lip gloss, a Walkman from Pat. Slump down in the chair the principal points to.

“Hope,” the principal says, in a painful molasses way, clasping his hands together and bringing them down over the crotch crease in his blue dress pants. He always was a pervert. “I really don’t want to have to suspend you again, but you aren’t leaving me much choice.”

“Shh,” you say, “the doctor said.” Or perhaps you say nothing at all.

Last period is English with Ms. Campbell. She’s only been here a couple of months, and rumor has it she’s only staying two years, some special program. She is young, that is true, and there isn’t the same boredom in her, ending class early, assigning coloring books for Christmas. These things don’t mean much to you. There is still a barrier there, and you are still on the wrong side. But sometimes when you look up suddenly, you catch her looking at you, straight on. Once, she called on you and you knew the answer.

While she’s writing on the board, some of the boys in the back make cracks about her ass and mime grabbing motions. She writes a poem on the board.

“After great pain, a formal feeling comes.” She reads the poem slowly, lingering, with a toss of her short brown hair. “As freezing persons recollect the snow—”

Turn towards the window that looks out over the asphalt parking lot, the mountains in the distance. It is fall again, chilly in the breeze and too hot in the sun, but soon there will be snow covering those mountains. The snow came rushing at you all of a sudden. It was the first time, and you were eleven. One moment you had been making a snowman, running and bending over to collect snow from the best patches, and then an icy white wetness in your hair and his hand slapping your face. There was a pain in your chest, the heart breaking is more than an expression. You looked down and saw blood, shocking on the white snow. Remember how bright the air was that day, how clear and bright, and how hungry you were afterwards. You went back to the house and ate six donuts, fast, like an animal. He squinted at you, as if through a telescope. “I have to lie down now, my head hurts,” he said. He went to his room and closed the door quietly, click.

December will make one year in the home for girls.

“…then the letting go,” Ms. Campbell reads. It is hard to know what to wish for, to let go, or to hold on. Ms. Jenkins, the counselor from the home, tells you that it is not your fault: your brother was a very sick boy, that Hank from McCaul’s gas station had done that to other girls before. She repeats this over and over again as if it were an answer, or a prayer like a hail Mary. Say it, say it again.

At the end of class, Ms. Campbell hands back the last paper. She makes a face like regret, tight but kind, when handing you yours.

“Anyone who got below a C, has to stay and check in with me,” she says, and takes a seat at her desk. After the bell, a line of students forms near her desk. You were supposed to meet up with Jason, but you dutifully wait your turn. There are two boys in front of you who are clearly pissed, digging their hands into their jackets and sighing. The girl speaking to Ms. Campbell now, chews gum and says “uh huh,” every so often. Your eyes are tired, so tired. Sit down in one of the chairs in the front row and cover your eyes with your hand, letting your eyelids rest. Open them, after a time. Look down and see that your hands are trembling, not from cold, but from something else. But you see also that you have two hands, one to tremble, and one to cover the trembling one with.

“Hope?” Ms. Campbell puts a hand on your shoulder and you jolt out of sleep.

“What?” you say sharply.

“About your paper,” she says, taking a seat next to you.

“Yeah,” you say. “What about it?”

“Well,” she says, flipping through it. “The ideas are good—it just needs a lot more development. It needs to be pushed farther….” There is more, but this is enough. Focus on her oval face, and the solid heavy jaw, almost like a man’s. Her hair is cut short just past her ears, not straight across, fashionable. Know that she is from a big city. As she speaks, imagine she is your friend, imagine you are at a restaurant and it is dark and noisy and she is trying to tell you a secret, but it is hard to hear.

“You’re smart,” she is saying, you can just make out over the loud music. “You’re really smart, Hope,” she says again, the words vibrating in the empty classroom.

“Yeah, well,” you say grinning, but you wish she’d kept it a secret.

In the coming weeks, pay more attention in Ms. Campbell’s class. Come to understand that Emily Dickinson was not simply crazy; this is not the whole story. Sometimes, hide a flashlight at the foot of your bed, and after Ms. Jenkins has made the rounds for lights off, take it out, pressing the book into the wall. A poem reminds you of telling a story, the way your grandma used to tell it, confusing as hell, but more and more familiar the more times you hear it. It comes to remind you of itself, of something else, of yourself.

See Ms. Campbell in the hall sometimes, in loose fitting jeans and a wool sweater like a sailor. She will be coming out of the teacher’s lounge, or getting a drink from the water fountain. She will smile wide and say, “Hi there, Hope!” Once, she placed her hand on your shoulder as she passed you. “Whoops!” she said, weaving by.

Another time she keeps you after class and gets carried away lecturing you on thesis statements, and you miss the bus. She is flustered, apologetic, and the sun has already disappeared behind the mountaintops. She insists on giving you a ride, though you resist, not wanting her to see the yellowing cement block building, the bars on the windows, not wanting her to think you belong there.

“Whatever,” you say, following her to the parking lot, but as you get into her old black convertible, your cheeks burn. It is a clear, cold evening with a biting wind, and the trees etch black skeletons against the dull sky. She shifts gears smoothly, her fingers surprisingly thin and delicate on the wheel. You talk non-stop to choke your awe, chattering about boys, aboutcars, about music videos, and she will nod and smile a big, toothy smile. To fill a silence say, “I was raped, you know,” tripping over this word that they have taught you to say, that you say all the time now. Say it, say it again. She will turn her head from the road and look at you as if it mattered.

“No,” she says, “I didn’t.”

“Yeah,” you say. “Twice. Well, that’s not really right. Two different men anyway.” She keeps driving, more slowly now.

“I’m sorry,” she says, with feeling. “I really am. That is not how it should be. It is not okay for it to be like that.” Then a Rihanna song that you love comes on the radio.

“God, I love this song,” you say. She reaches over and turns up the knob, and puts a hand lightly on your shoulder. Squeezes. You smile and turn away.

When the next paper is due, take some of your free periods in the library. Jason will be pissed, and Jason’s friend Hank who works at McCaul’s and who you still see sometimes anyway, will get in your face.

“What the hell are you staying in there for?” Slam the locker door closed in his face and keep walking. Work on it for four nights in a row, with the flashlight, scribbling into a marble notebook, crossing things out, scribbling again as the other girls in your room make their moves, their exchanges, their threats. Mary from the next bunk over will offer you a pack of cigarettes for your notebook, and you almost take it, but change your mind at the last minute. Commit yourself. Feel it getting worse each night, feel what you had unraveling. Once when you have it close to the way you want it, Tracy will tear it up and leave the scraps in your bed.

Be unable to tell your own voice, your own way of speaking from Emily Dickinson’s. Catch yourself speaking more slowly. In the big bathroom mirror in the group home, be surprised to see your own skin, your own hands. Fall asleep the last night, head on your notebook. In the morning, the flashlight will be dead and your paper will be seven pages of loose-leaf.

After class, wait for Ms. Campbell to be free. You will explain the situation. As she finishes talking to a girl with a ponytail, begin to doubt her understanding. You could turn and run.

“Hope?” she says. “What’s up?”

“Well,” you begin. But there is no beginning and no end, there is only the same boring story, not even told in a complicated or clever way. She looks at you, almost fearful, and you think that it is too bad you are not trying to fool her this time, this once, for she would surely believe you. There is a ringing noise in your ears like what is left over when you stand too close to a stereo speaker.

“Are you all right?” she asks. Have trouble breathing, feel as if your mouth is on fire, hate all that which you are, all the stories that have been told about you, even the ones that are true.

“I tried, I really did to make this one better than the last one. I made notes and I brainstormed and I underlined, all like you said, I—” That is it, for the hot tears roll down now though you are not sad, only furious.

“Whoa, hold on, Hope. It’s okay, really. We can talk about this—how about an extension till Monday? How about you just sit here and breathe a minute.” She guides you towards a chair near her desk. She sits down at her desk. “Now just breathe for a minute, go on.” Imagine there is blood and it is running down your leg and pooling in your shoe, then spreading to the carpet, bright as blood on white snow. Imagine there is a pain and it starts in your heart.

She will lean in close to you, looking in your eyes, straight on, and take your trembling hand between hers.

“It’s okay, Hope, really. It’s not the end of the world.” She looks as if she is somewhere far away and you try to go there too but you can’t because the room is too loud, so loud, roaring in your head like a bell. And you do not know what this wanting is, to be close to her, for the lines seem so blurry, bodies so soft, and your heart so vast and empty.

In a swift move, close your eyes, your face is upon hers and she tastes wet and like nothing at all. Feel yourself pushed off, your name called. Keep your eyes closed because you know when you open them there will be nothing left and that what she has said will not be true anymore, and all that there will be is a sound like a bell ringing, and then a silence.

At dinner, after Ms. Jenkins has said prayers, Tracy will come over and rest the top of her belly fat on the table in front of you.

“Heard you got a little sexy with the teacher,” she says, lingering over the words, sexy, teacher.

“Shut the fuck up,” you say, looking her straight on.

“You’re a little slut, that’s all you are,” she says, and though you’ve been called that hundreds, millions of times before, it seems true only now, in this last crossing of the line, this last act of blanketing. There is one body on another, the warmth of flesh colliding, slapping—what else is left?

Staring at Tracy’s fat, oily cheeks, vow that this is the last time you’ll be back in the home. That the next foster placement they find you will be the one. Pat had been the one, or so you thought. You and your brother had been placed with her when you were ten and he was thirteen after your mother got arrested for the third and final time. Pat had made jell-o cups with whipped cream and let you and your brother eat them in front of the T.V. She’d liked that you were pretty, entered you in the county middle school beauty pageant, bought you shirts with fake jewels on them. She’d yank a brush through your thick, mangy blond hair, no matter how many times it took.

But soon she started getting headaches, took to going to bed before it was dark out, watching the soaps on T.V. all day long. Sometimes you’d come home from school and she wouldn’t have moved since you left that morning. Your brother really started to push her buttons. She hated the way he stuttered, his ticks—he wouldn’t eat red foods: no steak, no strawberries, no red peppers, definitely no ketchup. Shrimp were a challenge. Beets would push him over the edge.

“Oh just eat it,” she’d say, shoveling beets onto his paper plate. But he’d just sit there blinking. By then, he spoke only in exclamations.

“No way, José!” he cried back.

It was during your second month of high school that they took you from Pat. One of your brother’s special education teachers noticed that he was coming to school in dirty clothes, his hair unwashed for days. On the home visit, the social worker opened the door to your brother’s door and nearly passed out from the stench. There were jars of curdling milk on the table, yellow and watery and thick, candy wrappers and Styrofoam takeout containers littered the floor, all mixed in with endless scribbles on scraps of yellow paper. Great scott! said one. Believe you me! said another. There were mice in the holes in the walls, moldy pieces of pizza between the sheets. Pat put out a hand to steady herself on the couch. She claimed she hadn’t known how sick he was.

After dinner, you debate carefully. You’re sure Tracy has something planned for you. Walk down the hall to the pay phone and check the slot on a whim. Shockingly, your finger feels a piece of loose metal in there, grabs a hold of it, a rusty quarter between your thumb and index fingers. You’re sure it’s a sign, and you dial Hank’s cell phone number in a frenzy.

“Hey, asshole,” you say when his scratchy voice comes on the line. “Wanna pick me up?” He will say yeah, and you will walk calmly to the bathroom, stand on the toilet seat and pull yourself up to the ledge, your arms hard and strong, and then weasel your way through the opening where one of the bars was sawed off. Jump down with satisfaction onto the dusty gravel. As you wait for Hank, wonder if you haven’t made a great mistake.

“So he raped you?” Ms. Jenkins had asked, in one of her sessions with you.

“Well, not at first,” you said, “but then…yeah, I guess. I wanted to stop. He pushed me up against the garage wall.”

“That’s rape, Hope,” she’d said. You shrugged.

“What difference does it make what you call it?” you’d asked. No one had ever been able to answer that question. Hank wasn’t so bad. He had a mean streak in him but he wasn’t so bad. Just a boy from around who was good with cars. He liked to go to the movies and put his hand down your pants.

He pulls up in a green pick-up borrowed from the garage.

“Hey, get in,” he says, and you do, stepping up into the cab and sliding into the grey velour seat next to him. “Where you wanna go?”

Stare straight ahead. Say, “I don’t fucking care. Just drive.” He will turn and start the car up, the engine rumbling beneath you, and you will wish to turn back, for a moment only. You could get out and run.

He parks in the high school parking lot. The floodlights on the football field are lit and they bathe the cab of the pick up in light so bright you can hardly even see Hank’s face, which is how it should be. He unbuckles the belt holding up his jeans and leans over, pulling you to him. Take his face in your hands and kiss him, hard, wanting something on you, in you, filling you up, tearing you open. He will pull down your jeans and jolt into you then, holding you hard by the flesh of your hips. Feel each individual finger grabbing you there. Close your eyes while he’s fucking you, shut yourself off, up, try not to feel the hard steering wheel in your back, the seatbelt buckle under your knee, and swing your hips to meet his. You’ll be damned if anyone’s gonna say you’re frigid. He’ll shift you then, pushing you down hard into the passenger seat and shoving into you, rocking fast and hard and cold, and you tremble holding onto the passenger side door. He reaches for your arms to pin them against the door and thrusts so hard you make a little cry of pain.

“Shut up,” he says, and slaps you one, right across the cheekbone.

“Stop,” you whisper, but he keeps fucking you, even harder. “Stop!” you say, louder, and bring up an elbow to push him off. He slaps you again, harder, with the back of his hand, and you go crazy wild, trying to push him off. He holds you at arms’ length, and laughs.

“Shhh, sweetheart, you don’t want to do that,” he says, and the light of the parking lot floodlights reflects off something shiny, the blade of a big Swiss army knife. “Easy now, girl,” he says, taking the knife and making a light surface cut on your right breast which is exposed where your shirt’s been torn. Be unimpressed, you’ve done worse yourself, but when he takes the blade with his thumb and presses it into your neck, saying, “Come on now, you don’t want to do that,” you stop to consider. Your arm’s been twisted, your favorite shirt torn. You’ll have bruises on your face for weeks. Where is left to go? You’ll be locked out of the group home, maybe have to sleep outside. You’ve been raped, over and over. The body seems just a place to put things, to stuff up and plug, to bandage, dab, repair, to bleed and bleed. Think of Ms. Campbell, of her telling you that you’re smart, of her saying that is not how it should be, it is not ok for it to be like that. Think of Tracy and her fat, pimply face, but the only friend you’ve got, her heavy sighing in the night your lullaby for a year now, maybe your lullaby forever. Think of your brother, locked somewhere too, spending his days in front of a T.V., writing on his little slips of yellow paper. Last month a letter came from him. Greetings from the loony bin! was all it had said, and there had been a little picture of a palm tree drawn in pen. Smile, thinking of it now.

“So, what’ll it be?” Hank asks, gyrating his crotch a little bit, and pushing the blade harder into your throat. Breathe in hard and prepare. Spit in his face, and brace yourself to make a fist. Then, squinting, punch him hard in the nose. Scramble for the car door handle, your body falling hard onto the cold asphalt, but get up and run for your life. He is swearing and shouting after you, and you hear the car door close and his footsteps behind you, but you keep on running. For if life were all pain and logic, who would want it? But you want it, god, do you want it.

About the Artist

Brittany Whiteman, University of Connecticut

Brittany Whiteman of University of Connecticut is a photographer, painter and designer currently living in Connecticut. You can view more of her work on her website, brittanywhiteman.com.

No Comments